It is safe to say that never in the history of systematic ornithology has there been so much talk about English names as now. And rightly so: the stakes are higher and our responsibilities graver today than ever before. Words matter, names matter, and there should be nothing easier in the difficult matter of inclusivity than simply changing a few—restoring some, creating others—to make more of us feel more welcome in the field.

This is not, however, the first time that the process of assigning vernacular names to the birds of North America has been the subject of serious discussion. Conducting field work in New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania in the 1790s, the French ornithologist Louis Pierre Vieillot found himself forced to name, and in a number of cases rename, many of the birds he encountered. A decade before Wilson and a quarter of a century before Audubon, Vieillot set out to prepare a handbook to all the continent’s birds; two volumes were published, the remaining two extant only in fair copy.

It is in the Avertissement to his first volume, dated 1807, that Vieillot addresses the matter of naming. The text includes English names where they are available, transcribing them more or less phonetically. But Vieillot found himself obliged to change, or to create, vernacular French names for many species that were still unknown to European scientists or that had been coined with an inadequte knowledge of the birds’ habits and appearance. His comments clearly attest to the care he devoted to the task.

I am aware that changing names is greatly disadvantageous to the study of natural history; but that cannot apply to the names given to birds that have been incorrectly classified…. As to the names borne by foreign birds in their home country, that is to say, the names imposed on them by the human natives of the place, one should adopt them in preference to the designations, so variable, that have been fabricated for them in Europe: for the native names almost always reflect the bird’s song or the call, a behavior or a characteristic food. These local names being primitive, they must never vary, regardless of the language one is using them in; and since they are more meaningful than arbitrary names, the concept affixes itself with greater clarity to the object perceived.

Vieillot’s reluctance to change the received European book name of a bird is based not just in his respect for nomenclatural stability, but in a faith in the authenticity of “primitive” names, which he seems to consider not only original but essential, linked realiter to the species in ways discernible only in the living animal.

On the same basis, Vieillot also rejected the folk names assigned American birds by European colonists and their descendants.

I shall also disregard the names that the European inhabitants of America have given the birds, since those names are not expressive [as are the “primitive” names of the native peoples]. That happens because they are hardly at all concerned with the study of nature.

It is knowledge that makes a name authentic, and Europeans in America, seeking only material advantage, refuse to learn anything about any natural object that is not immediately useful.

If by chance a tree, a plant, a bird, an insect does catch their eye, their first thought is to compare it with a European counterpart. As soon as they discover an overall or even a partial similarity, without considering details, they give it the same name as the European object.

This, Vieillot points out, is why America, too, has its orioles, its blackbirds, its goldfinches, its nightingales, and its ortolans. In the United States and British Canada, “any bird in which yellow predominates” is a “yellow-bird,” those that are chiefly blue are called “blue-bird,” and the name of “snow-bird is given indiscriminately to every bird that appears only in winter.”

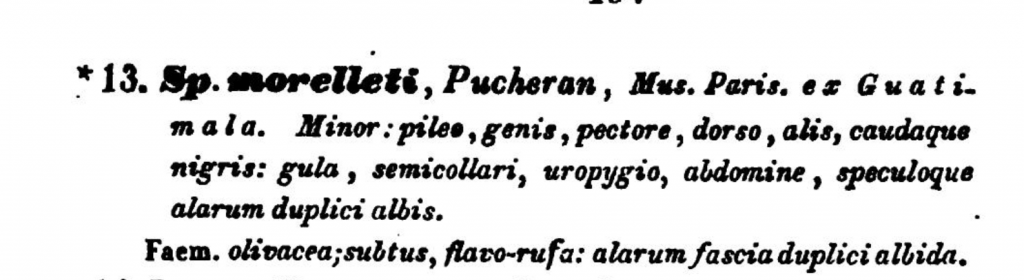

Another group of book names is rejected with equal vehemence. Vieillot is at particular pains, he says, to avoid names that invoke a bird’s geographic origins to distinguish it from other species. He agrees with Montbeillard, writing a generation earlier in Buffon’s Histoire naturelle, that such names are necessarily less authentic than those invoking the characters inherent in the living animal; furthermore, a species may have a range much wider than the single country it is named for, and it is not infrequent that a specimen received from one place in fact originated in another. Vieillot takes as one example the yellow-green grosbeak, named by Linnaeus canadensis for its supposed home:

But no traveler has found it there, and might it not instead have been brought from Cayenne or South America, and then shipped from French Canada to Europe?

This case is notorious even today, and Vieillot was right; Linnaeus had simply misread his source’s name cayenensis as canadensis and assigned that name to a bird whose genuine range comes no closer to Canada than Panama.

One category of names—the category most contentious today—goes entirely unmentioned by Vieillot. Patronyms, based on the name of a person (the eponym) more or, often, less somehow connected to the organism named, simply do not feature in his discussions here. Patronymic naming in the vernacular was not entirely unknown to Vieillot and his contemporaries: George Edwards had named the Pompadour cotinga in 1764, and the well-known orange-throated warbler was graced with Anna Blackburn’s surname as early as 1785. As those examples suggest, however, and as a cursory review of the early European names for American birds appears to tentatively confirm, the practice was at first largely an anglophone one. Elsewhere in Europe, patronymic naming practices seem to have become fashionable in the vernacular only in the 1830s. The authors of most early names in scientific Latin, too, seem to have eschewed naming birds for people; the 1758 edition of Linnaeus’s Systema naturae, for example, transmits only one patronymic bird name, Psittacus alexandri, along with four other species named for mythological figures.

It was perhaps inevitable that Vieillot himself has had his name pressed into service as eponym for half a dozen species. Just as those epithets have assured the French ornithologist a sort of immortality, so too have the standards he set forth for the naming of birds long outlived him, still thoughtful and still worth considering more than 200 years later.