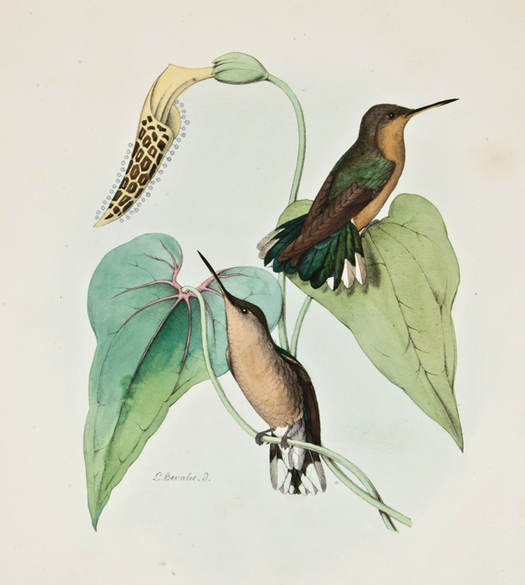

Another sneaky bird, this one a hummingbird, named Trochilus fallax almost 175 years ago. It’s often easy to figure out what the original describer had in mind in styling a bird “deceitful,” but not this time.

When Bourcier and Mulsant named this species in 1843, they were entirely forthright about their lack of confidence in its truthfulness, calling it “deceiver” in both French and scientifickish. But they didn’t tell us why.

What’s mysterious to me seems to have been perfectly straightforward to the namers’ colleagues and contemporaries. When it came time to dismantle the venerable catch-all genus Trochilus, the inventors of new generic names simply came up with what were essentially synonyms to fallax. Charles Bonaparte called it Doleromyia in 1854, “deceptive fly-bird,” and Cabanis created a diminutive Dolerisca, the “little trickster.”

When Mulsant published the Histoire naturelle des oiseaux-mouches starting in 1874, he took over Bonaparte’s genus name, correcting the spelling to Doleromya, and fancying up the vernacular name to “doleromye trompeuse.”

And still not saying why.

The explanation, or an explanation, came in 1881, in the Catalogue descriptif of Eugène Eudes-Deslongchamps.

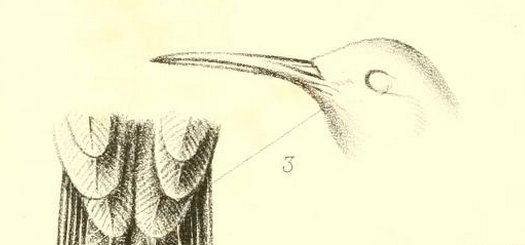

The museum in Caen holds the type specimen on which Bourcier based his Trochilus fallax. The specimen is quite well preserved and very carefully prepared…. Externally, this pretty little bird far more closely resembles a Leucippus than any other bird, but the evenly curved bill is very different. The general colors, and in particular the distribution of white spots on the tail, actually recall a miniature Campylopterus saberwing. It is likely for these reasons that Bourcier assigned the species the name fallax.

So there we have it. Or maybe not.

Eudes-Deslongchamps’s mention of Leucippus points in another direction. That name — which happens to designate the genus to which our bird, the buffy hummingbird, is currently assigned — most likely commemorates the Pisan prince Leucippus, who disguised himself as a girl to get closer to his beloved Daphne (it didn’t work out well for either of them, as you may recall).

The bird name was coined in 1849 by Charles Bonaparte, who obviously forgot he’d done so when he devised Doleomyia five years later. Bonaparte doesn’t happen to mention what he intended by adopting the name from classical mythology, but as usual, James Jobling makes a very good suggestion:

both sexes of the buffy hummingbird share the same plumage.

The deceit, then, would consist in each sex “hiding” in the plumage of the other.

I have no doubt that Jobling is right, and that that is exactly what Bonaparte had in mind. The only problem is –and it’s Bonaparte’s problem, no one else’s — that Bourcier and Mulsant weren’t thinking anything of the kind. Their 1843 description makes reference to only one individual, and an unsexed individual at that, so they could hardly have thought themselves tricked by the lack of sexual dimorphism.

Moreover, three decades on, in the Histoire naturelle, Mulsant has no difficulty tallying the characters that distinguish the age and sex classes of this species. But he notes that fallax

shows some similarity to the species of the subgenus Threnetes in certain respects and in other respects approaches various members of the genus Leucolia.

This is not unlike Eudes-Deslongchamps’s observation seven years later — but invoking affinities to a different group of similar species.

I’m stumped. As I go through the sources and ponder, though, I begin to wonder: maybe what is “fallax” about fallax is the name itself, a jocular deception perpetrated on the future by two Frenchmen 175 years ago.