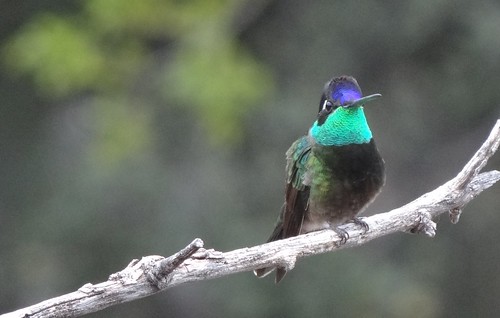

Of all the breathtaking lot of parrots, few are as likely to leave the birder agulp as the stunning blue-headed parrot, a widespread and common bird from southern Central America to Bolivia and Brazil.

The dazzling swarm in the photo above was at one of the famous clay licks of Peru, but this species burned its way into my memory years before I saw them there, when a single individual flew beneath me as I was perched high on a tower in Panama, its head out-bluing the tropical sky.

And being who and what and as I am, at the very same moment a question pierced my mind, one that has nagged me ever since: What’s so menstruous about Pionus menstruus?

Nowadays, questions about the scientific names of birds are easily answered. We have James Jobling’s considerable store of erudition at our fingertips, and in the few cases where that doesn’t help, all the wealth of the Biodiversity Heritage Library is there for the mining.

But I’m stymied.

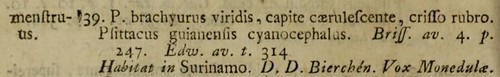

The name is Linnaean, appearing first in the twelfth edition of 1766.

The Archiater’s Latin diagnosis of the newly named parrot is quite thorough, beginning with the fact that Dr. Petrus Bierchen reports from Suriname that the bird has a voice like a jackdaw.

The body is the size of a turtle dove’s. The head and neck are bluish, the feathers dusky but blue at the tip. The back and wings are green. The wing coverts are yellowish green. The belly is greenish, the feathers bluish at their tips. The remiges are green, dusky on the inner vane. The rectrices are green, becoming blue at their tips, but numbers 1, 2, and 3 are blood-red on the inner vane, from their base halfway out; the outer vane is entirely blue. The crissum is red, the tips of the feathers yellowish blue. The bill is horn-colored: the upper mandible reddish on the edges. The eyes are black. The eye rings are bluish grayish.

No real onomastic clues here, and neither of the authorities Linnaeus cites — George Edwards’s 1758 Gleanings and the fourth volume of Mathurin Brisson’s Ornithologie — offers any hints. It is notable — if purely incidental to my question — that all three of the scientists relied on different sources for their knowledge of the bird: Linnaeus’s type had been supplied from Suriname, Edwards was working from a live individual in London, and Brisson had access to a specimen labeled as originating in Martinique.

Buffon and his collaborators likewise seem to know nothing about the odd Linnaean name. The OED and the Century are of no use, and we’re stuck with the prospect of a systematic search through “the older literature,” which in North American ornithology tends to mean anything before the publication of Ridgway, a scant century ago.

Johann August Donndorf’s Zoologische Beyträge, a commentary on Gmelin’s edition of the Systema, is one source Ridgway overlooked or declined to exploit for his North and Middle America (he would not have been the first to rail against Donndorf’s sloppiness as a bibliographer), but it is often productive of otherwise obscure eighteenth-century names and publications. In this case, it sends us to Statius Müller’s translation of Linnaeus, where the German systematist coins the name “Blauhals” (“blueneck”) for this species — and incidentally asks himself the same question that occurred to me more than 200 years later in Panama.

We have named it the Blauhals because we are unable to explain the name “menstruus.” I suspect that in the case of many names Linnaeus did not even intend that their meaning be understood, as otherwise he would have explained the more obscure among them himself, or assigned clearer names.

Vieillot, usually a bright light in the otherwise dim bibliographic jungle, has no comment on “menstruus,” but to make up for it, he tells us that in Paraguay the bird is called “siy,” an echoic name. Levaillant likewise says nothing about the Linnaean name; his two accounts of the species, though, are a really fine example of this explorer and ornithologist at his best, addressing everything from sex and molt to land use changes in coastal South America.

And so it continues, right up to today: as far as I can find, no one seems to have known Linnaeus’s motivation, or even to have speculated about it in print. Time to widen the search, perhaps.

If I google correctly, the blue-headed parrot is the only bird in the world currently in possession of a species or subspecies epithet “menstruum/a/us.” In 1786, though, Giovanni Antonio Scopoli gave a formal diagnosis and Linnaean binomial to a woodpecker that had been collected in the Philippines by Pierre Sonnerat a decade earlier. Sonnerat described his bird:

… the green woodpecker of the Isle of Luzon [has] the entire body a somewhat dirty green; the top of the head is faintly spotted with gray; the flight feathers of wing and tail are blackish; the upper tail coverts are very bright scarlet red, forming a large patch; the feet and bill are blackish.

Scopoli assigned this bird the name Picus menstruus, like Linnaeus before him offering no hint of an explanation. What do the two birds have in common, the parrot and the picid? Linnaeus distinguishes his parrot from the one that precedes it on the page by undertail color: he writes that the latter is “similar to P. menstruus, but its undertail is not red.” Scopoli adds to his summary of Sonnerat’s woodpecker account that “the rump and undertail are red” (my emphasis to show the addition).

Can it be that “menstruus” here means not simply “monthly” but “catamenial”? Entomology provides what may be a significant parallel: the sarcophagid name Syctomedes menstrua is a junior synonym of Syctomedes haemorrhoidalis, both names alluding to the red genitals, as if colored by flowing blood.

I know very little about Scopoli, the namer of the Luzon woodpecker and the eponym of a shearwater and a drug that helps when looking for the shearwater. Linnaeus, though, was more than capable of ignoring the blue-headed parrot’s blue head to reach for a more scurrilous name. His own contemporaries reproached him for the poor taste of some of his inventions, that notorious

Linnaean obscenity [and] licentiousness…. Science should be chaste and delicate. Ribaldry at times has been passed for wit; but Linnaeus alone passes it for terms of science.

Psittacus menstruus appears to be yet another example.