Or, perhaps, neither.

Yes, this is a gorgeous reddish egret, in south Texas last week during one of the field trips at VENT‘s 45th Anniversary Celebration, based in McAllen. And yes, we spent some very rewarding time discussing the identification of this and the other white herons of the area. It can be subtle, but I think the fine studies we had left everyone feeling more confident about picking a white reddish out from a swarm of late summer egrets.

But pondering this bird, or any bird, raises questions beyond the details of identification. Two occurred to me on the drive back to McAllen, and I’ll try to answer one of them here.

To wit: How, why, and by whom was the scientific name of this bird changed from rufa to rufescens? There should be a straightforward and unexciting answer, but in this case, the process—or rather, the apparent absence of process—offers a quick glimpse into the quiet workings behind the scenes in the early days of the American Ornithologists’ Union and its Check-list.

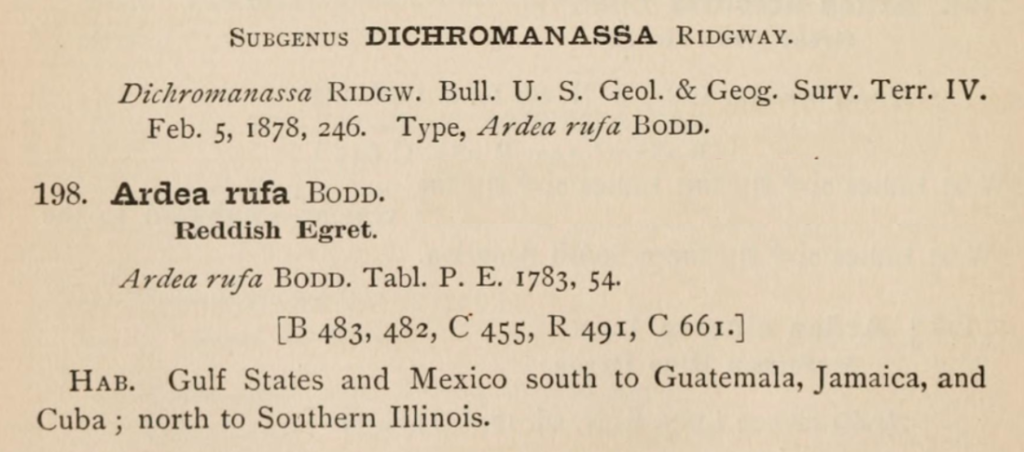

The first edition of the Check-list names the bird Ardea rufa, crediting the name to Pieter Boddaert’s key to the Planches enluminéez produced to illustrate Buffon’s HIstoire naturelle. Boddaert often gets bad press for having swooped in to assign Linnaean binomials to the birds Buffon and his collaborators identified only in French, but without him (and Klein, and Temminck, and the Catalogue of Birds in the British Museum), those 1008 plates would be even more unwieldy for the modern user than they already are.

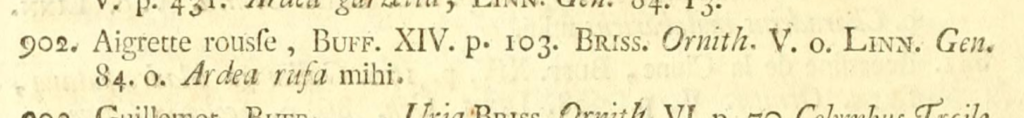

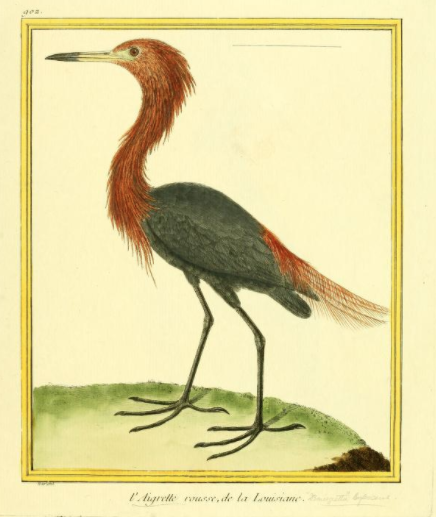

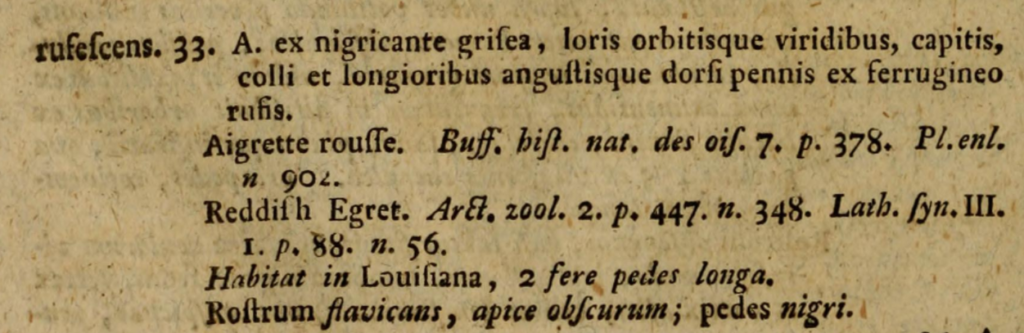

In any case, Boddaert gave Buffon’s “Aigrette rousse” from Louisiana the scientific name Arda rufa, and he left no doubt as to the author of that name: “mihi,” “mine.” The type specimen, so to speak, of the newly christened species is the bird depicted by Martinet on the 902nd plate of the Planches enluminées:

There can be no doubt that the bird Martinet painted was a reddish egret, right down to the bicolored bill and the odd bristly feathers of the head and neck. But there is a problem: Boddaert’s name rufa had been used before, by Giovanni Antonio Scopoli (him of shearwater fame), who in 1769 assigned it to a bird in his personal collection.

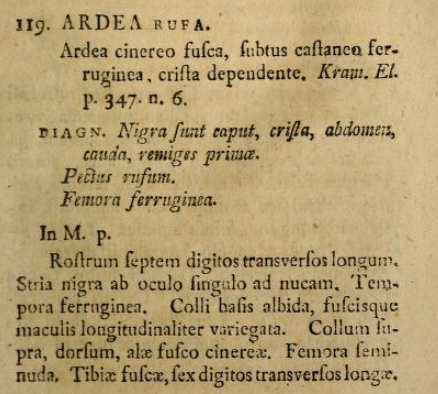

Scopoli’s diagnosis of the species is vague enough to suit any of a number of heron species, but the fuller description includes a white head stripe and a whitish lower neck with yellow-brown streaks. The cited passage from Wilhelm Heinrich Kramer’s Elenchus only deepens our uncertainty:

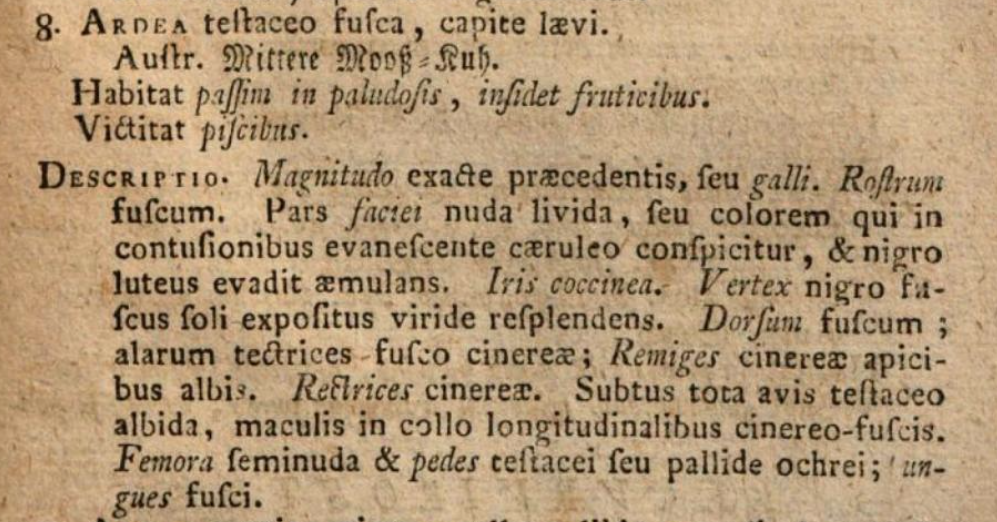

Not only is Kramer’s bird characterized by entirely pearl-white under parts and a brown-streaked neck, it has an Austrian vernacular name, Mittere Moos-Kuh, the mid-sized bittern (“fen cow”). This cannot possibly be a reddish egret, a species known only from the American tropics.

Nevertheless, on the strength of Boddaert’s reliance on Martinet’s plate, the name rufa was attached to the reddish egret, and it survived to be taken over by the AOU a hundred years later. (Kramer cannot be the author of the name because the Elenchus is not binomial in the sections dealing with birds and other animals.) In the second edition of the Check-list, though, something changes.

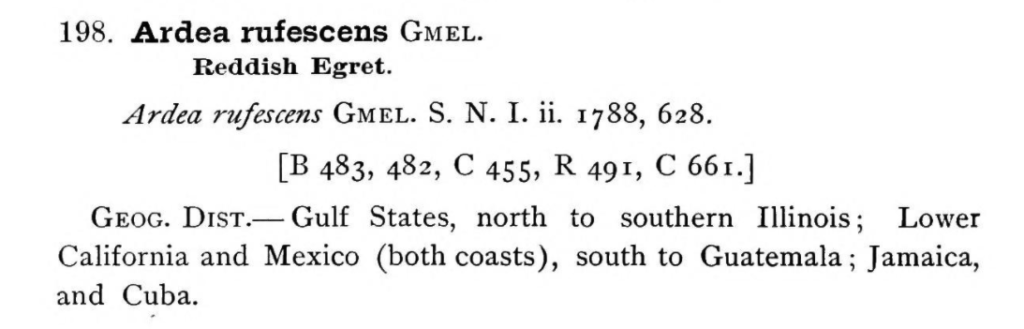

The scientific name has gone from rufa to rufescens, and the authority for the name is no longer Boddaert but Johann Friedrich Gmelin, the author/editor of the thirteenth, posthumous edition of Linnaeus’s Systema naturae.

Gmelin’s diagnosis is accurate and appropriate, and he even hints at the odd shape and structure of the feathers of the head and neck (“rather long and narrow”). He also cites as the first work in the brief synonymy the same plate and text from Buffon as had Boddaert.

Boddaert’s name, published in 1783, enjoys chronological priority over Gmelin’s, which did not appear for another five years. But the problem with rufa, obviously, is that it was itself preoccupied by Scopoli’s, who, equally obviously, had applied it to another species, most likely the purple heron. Replacing it with rufescens, as the AOU did in the second Check-list, should have been a routine matter chronicled in one of the Supplements—but I find no mention of this name change in any of them published before the appearance of the second edition, in 1895. Instead, rufa became rufescens without notice, simply popping up in the 1895 edition without having been introduced in any intervening AOU publication.

How exactly that happened isn’t clear from the sources available to me, but I have a suspicion.

The first clear statement of the problem was published by Robert Ridgway in 1887, in the Appendix to his Manual: Because the name Ardea rufa is preocuppied (by Scopoli, 1769) for another species [generally identified as the purple heron, Ardea purpurea], it becomes necessary to substitute the next in order of date . . . . Ardea rufescens Gmel.”

Ridgway was right, as (what strike me now on rereading as) my (rather labored) notes above affirm. He was also, of course, a member of the committees in charge of producing the first and the second editions of the Check-list. Naturally his discovery and the name change that followed from it were accepted and incorporated into the new edition, without public comment. If it were today, the change would have been formally proposed and voted on, and the result would appear in a Supplement before its eventual publication in the next edition of the Check-list.

A hundred thirty-five years ago it was different. The committee, and mutatis mutandis the AOU itself, could function as a small group of well-connected men who, for the most part (Elliott Coues was part of the gang, too), respected each other’s opinions so greatly that they found it unnecessary to fill anyone else in before the fait was accompli. It’s just a little glimpse, but a telling one, into the earliest days of an organization that still had a lot of democratization ahead of it.