In the later years of his life, I am told, Roger Tory Peterson enjoyed using the academic title “Dr.,” a reference to the half a dozen degrees honoris causa awarded him by half a dozen American institutions.

It’s embarrassingly poor form, of course, to use the title when it hasn’t been earned. Be that as it may, the practice of bestowing honorary higher degrees on ornithologists was already a venerable one in 1952, when Peterson received his first, from Franklin and Marshall College in Pennsylvania.

In 1825, for example, Princeton granted an honorary degree to Charles Bonaparte; it isn’t clear whether Bonaparte was present at commencement to receive it, but the circumstance lends a bit more substance to the petulant question Patricia Stroud reports as addressed that summer to his stingy father, Lucien: would he please send money to help support Charles and his family, or “does he want him to accept a professorship in one of the universities of the United States”?

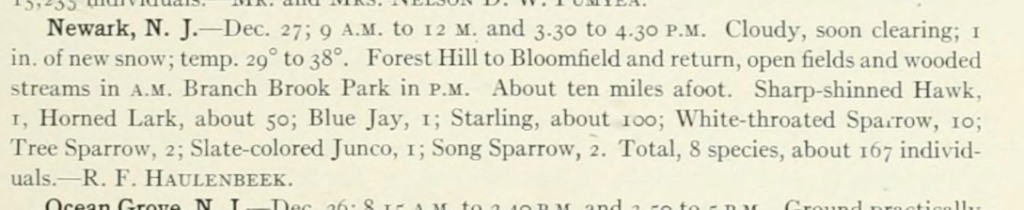

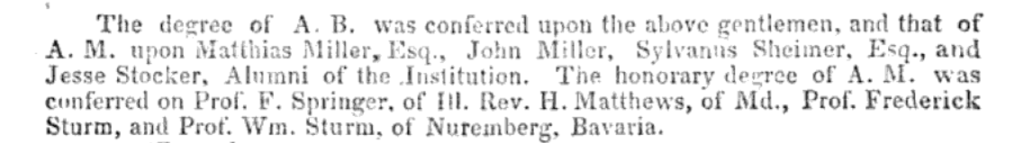

It is perfectly understandable that Peterson, an American living in an age of easy travel, or Bonaparte, a provisional immigrant spending most of his time just a couple of hours south of Princeton, should be the recipient of an academic honor from an American university. But what are we to make of this, from the Literary Record and Journal of the Linnaean Association of Pennsylvania College in autumn 1848:

Pennsylvania College, now Gettysburg College, was founded by German Lutherans, but the conferral of honorary degrees on the brothers Sturm of Nuremberg—who never once visited the United States—still seems odd, and the kind archivist at Gettysburg was able to establish no further connection between the still-young institution there and J. H. C. Friedrich and J. Wilhelm Sturm, prominent naturalists and artists in mid-century Bavaria.

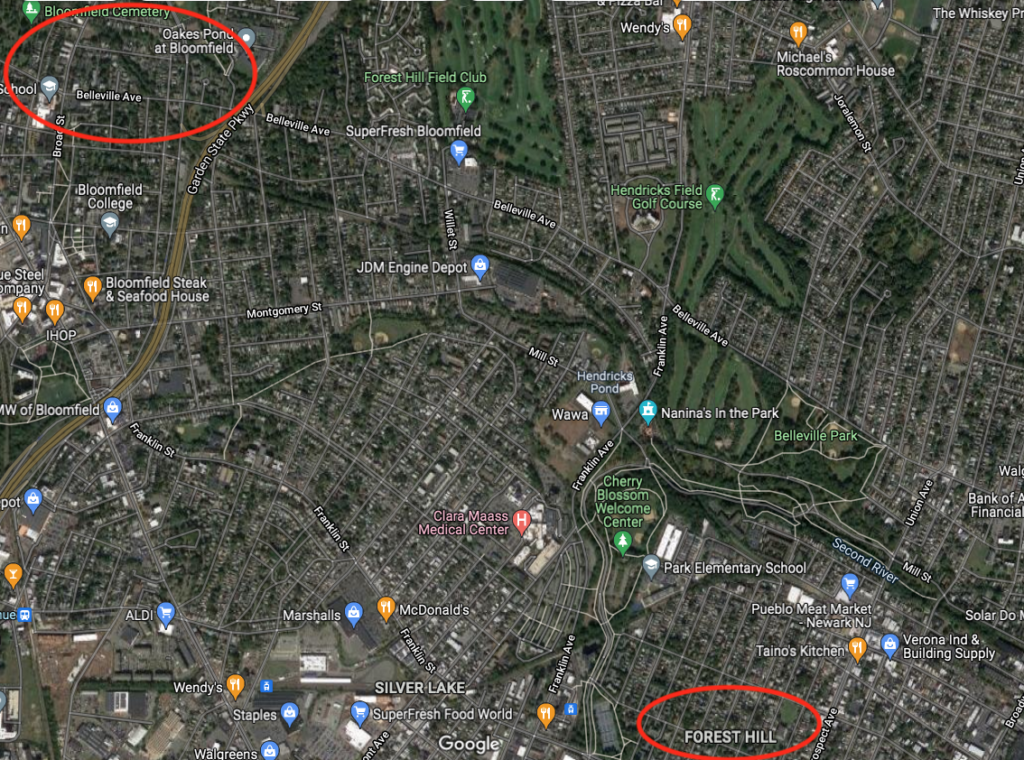

The brothers’ father, the entomologist, botanist, and engraver Jacob Sturm, had himself enjoyed international celebrity among naturalists on both sides of the Atlantic, with honorific membership in the Maclurean Lyceum and the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia and the General Union Philosophical Society of Dickinson College in Carlisle, Pennsylvania. He was so well known in that state that on the occasion of a sojourn in Germany, John Gottlieb Morris, a graduate of Dickinson, undertook a journey of 200 miles to visit Sturm in Nuremberg, in anticipation of “the richest zoological treat.”

Obviously starstruck, Morris “examined the extensive collections and spent three days most delightfully in the society of this excellent old man.” That visit was also the occasion for Morris to meet the two younger Sturms, themselves “fast rising to eminence.” Their own collections were notable for the most extensive series of hummingbird specimens Morris saw anywhere on his European travels, and he was equally impressed to see that the brothers (who, like the sons of Audubon, had married sisters) were in possession of the same “extraordinary artistic talents” as their father and grandfather.

Morris had corresponded with Jacob Sturm for some five years before he met him, and after their time together in Nuremberg, he maintained the connection in letters and in the transatlantic exchange of specimens. The Sturms, pére et fils, sent their American colleague many of their publications and “other valuable books.”

In 1832, Morris had been among the founders of Pennsylvania College, and he would go on to teach natural history there and to sponsor the college’s Linnaean Association. It’s small wonder that he should have used his influence to have his institution honor his Bavarian fellow-naturalists, especially as their father, Jacob Sturm, Morris’s original contact, was in an unstoppable decline.