Almost five weeks left to see the final installment of the three-year Audubon show at the New-York Historical Society. If you haven’t gone, go; if you’ve gone, go again.

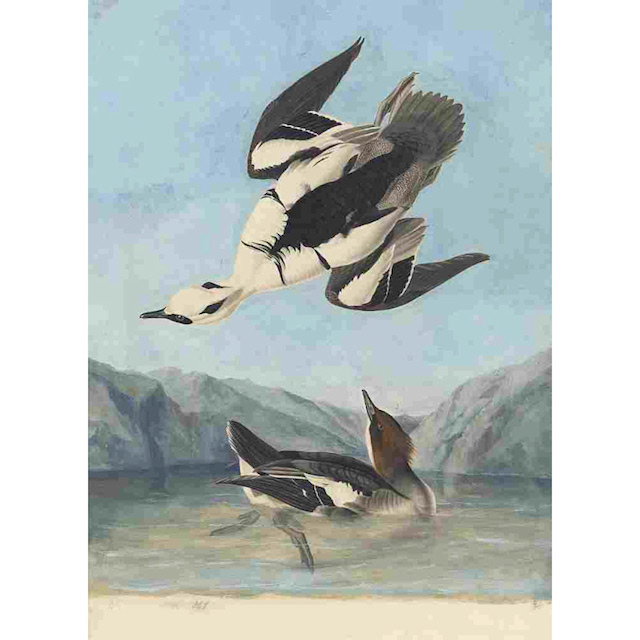

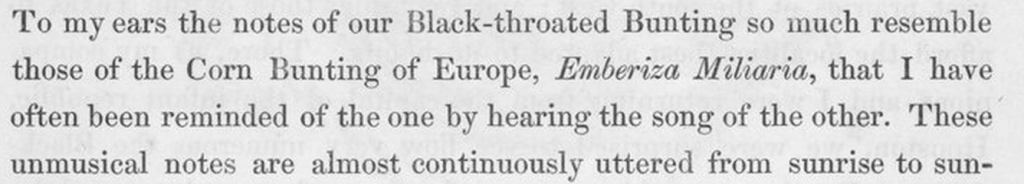

Unless you’re very, very young or of very, very long-lived stock, this is one of those rare opportunities that can be truly described as once in a lifetime. Starting in 2013, continuing last spring, and ending now on May 10, all (all!) of the original watercolors Audubon painted for The Birds of America have been on display — not the famous plates reproduced for sale to the subscribers, but the paintings themselves, from Audubon’s own brush. They’re an eye-opener, for would-be sophisticates who have long dismissed Audubon as kitsch and for birders hoping to discover more about Audubon, his times, and his birds.

I visited again last week, and was once again bowled over by the technical skill, the compositional imagination, and, yes, even the beauty of many of the paintings; I was not alone in standing rapt before the American bittern last week. But there’s a lot more to do at this exhibition than just ooh and aah.

-=-=-=-=-

One of the first decisions the curator, Roberta Olson, had to make when planning her exhibition was the sequence in which to present the more than 435 (!) objects to be displayed. In a canny move indeed, she settled on an order created by Audubon himself: the paintings have been shown not in taxonomic order, not in the order in which they were prepared, but in the order in which they were copied by the engraver and shipped to the subscriber.

Notwithstanding a nonsensical comment in the exhibition text — Audubon “believ[ed] that this order resembled that of nature” — that sequence was, and is, purely arbitrary, motivated simply by Audubon’s and his publisher’s eagerness to keep their subscribers’ interest by alternating big birds and small. For the modern viewer, this arrangement has the disadvantage of separating the images of similar birds — even in some cases images of a single species — and rendering direct comparison impossible; but there was no better solution, and this one has at least the advantage of giving the viewer an experience like unto that of the original subscribers opening their tin boxes of plates.

In this third and final installment, the sequence also makes abundantly plain what the exhibition texts (repeatedly) call Audubon’s “rushing toward the finish line on the project.” We see the paintings becoming more crowded, with more birds and, in many cases, more species to the sheet, and much more clearly than before, we see Audubon painting for the engraver, producing images intended from the start to be parted out and recombined into “composite” plates.

Unfortunately, that crowding is reproduced this time around in the physical space devoted to the exhibition. Where the earlier installations spilled pleasingly into the hallways and a second, smaller gallery, the paintings this time are all hung in a single large room. Not only is the wall space separating livraisons confusingly little, but many of the paintings are placed so high that they can hardly be enjoyed, much less studied. Binoculars, or a stepladder?

This one, for example, was far out of my visual reach, and I would have relished the chance to see it at eye level — especially given that the bird, which was not engraved for the Birds of America (the plant was), is identified as a Bachman’s warbler. In life and in the image above, it is obviously a mourning warbler, ironically enough a species Audubon probably saw less often than the Bachman’s.

This is not the only mislabeling in this installment. Two different tropical siskins in two different paintings are misidentified as lesser goldfinches; one (in the watercolor that would become Plate 433) is the yellow-faced siskin of Brazil, the other (400) is the widespread black-headed siskin. (Audubon himself corrected the first error in the Synopsis.) The shorebird hanging beside two black-bellied plover paintings is certainly not a dowitcher, as the exhibition label suggests, but rather a poorly remembered red knot or, perhaps, another black-bellied plover. And I suspect that with its big orange throat pouch and conspicuously fleshy lore, Audubon’s “Townsend’s cormorant” is not a Brandt’s at all but a double-crested.

Yes, looking close turns up these lapsus, but looking close also offers some spectacular insights into the Audubonian process. Especially revealing are the penciled traces of dialogues between the painter, his agents, his engraver, and even the eventual recipient of the plates. Next to the Forster’s tern, for example, Audubon writes several lines about an undescribed species he had seen by the “thousands” in New Orleans in the winter of 1820-21; but without a specimen,

[I] dare not publish it, I have notwithstanding named it “Black-billed Tern” Sterna Ludoviciana J.J.A.

They were winter Forster’s terns, of course, but even this short note gives us a glimpse into Audubon’s concern for the accuracy of his work — and a certain anxiety about its reception.

The most complex of the conversations on display this time is certainly that inscribed on the painting of the rufous hummingbird. Audubon here issues detailed instructions to both Havell and his son Victor, while his crossing out of one name — “Nootka Sound Humming Bird” — and replacing it with another –“Ruffed Humming Bird” — engages both the past and the future, as Audubon does justice to his nomenclatural predecessors and simultaneously places himself in the taxonomic vanguard.

One of Audubon’s notes, on his painting of the pine grosbeak, shows the intensity with which at this point the artist was thinking of the relationship between the images in the Birds of America and the texts of the Ornithological Biography. Beneath the crimson bird, he writes

Pay attention to Note diseased legs!

Indeed, the left foot of the male grosbeak in the painting is grotesquely thickened — a feature Havell omits from the engraved plate. In the Ornithological Biography, however, Audubon explains what he meant to have illustrated. He quotes his Nova Scotia correspondent Thomas M’Culloch:

These birds are subject to a curious disease, which I have never seen in any other. Irregularly shaped whitish masses are formed upon the legs and feet. To the eye these lumps appear not unlike pieces of lime; but when broken, the interior presents a congeries of minute cells, as regularly and beautifully formed as those of a honey-comb. Sometimes, though rarely, I have seen the whole of the legs and feet covered with this substance, and when the crust has broken, the bone was bare, and the sinews seemed almost altogether to have lost the power of moving the feet.

This is not the only example where the instructions on the watercolor were ultimately rethought and revised. Had Audubon’s original plan been followed, his plate 390 would have been completed with two dickcissels; instead, a lark sparrow came to occupy the space left at the top of the sheet. Here and elsewhere among the paintings preparatory to the composite plates we find the poses of individual birds obviously planned to ease their insertion into new contexts, the logical conclusion of the “collage” technique Audubon experimented with throughout his career.

One of the most tantalizing annotations belongs to one of the most fascinating paintings (this one hung right at eye level), that of the Townsend’s bunting. Unfortunately, the extensive inscription, which covers several long lines next to the figure of the bird, was erased at some point, though enough dim traces remain that it would likely be recoverable, at least in part, from the right angle under the right light: trivial though the content might prove to be, it could still double the nearly first-hand information we have about the bird — and perhaps even cast a little much-needed light on the recent second record of this mysterious animal.

Close looks at others of the paintings on exhibition here could contribute to other open questions, too. The apparently increasing incidence of pink-tinged plumage across several species of gull has puzzled observers for a decade or so now; but so far as I know, no one has pointed out that Audubon’s 1829 laughing gull painting shows the adult’s underparts nearly covered by a saturated dull rose. Havell’s plate does not.

Other elements of the original watercolors may be less potentially significant, but are delightful all the same. Behind Audubon’s exquisite least sandpipers is a roughly sketched landscape; one wonders what Audubon had in mind when he penciled in two donkeys, one standing and the other in repose, and why the charming scene was taken over neither by Havell nor in the octavo edition of the plates.

It has been a joy these past three years to come to know Audubon as a painter of shorebirds — and to recognize in him one of the very best of that rarefied lot. Even Homer dozes, though. As I lingered over the two (and a half? — see above) black-bellied plover watercolors on display, it suddenly struck me that there was something missing in one of the birds otherwise so well painted.

Two somethings, in fact: the basic-plumaged plover’s hind toes.

Neither this nor the inaccurate wing pattern of the female northern shoveler was corrected in the engraving. By no stretch of the imagination earthshaking, but still worth noticing.

And noticing is what birders do best, isn’t it?