The sad result of having left a Canada Goose in the dryer too long:

British Columbia, October.

The Experience of Birding

Today marks the bicentennial of the death of Pierre Sonnerat, explorer and author of important early works on the natural history of New Guinea and Indochina.

Sonnerat was the nephew of Pierre Poivre (yes, the original Peter Piper) and the artistic assistant to Philibert Commerson, linking him to some of the most influential naturalists of his day.

Like Commerson and Poivre, Sonnerat was primarily a botanist — he even has an entire family of plants named for him (though apparently, fide our friends at Wikipedia, the Sonneratiaceae have now been lumped with the loosestrifes). The reports of his voyages to the east, though, are full of enthusiastic, colorful, and in part perhaps fictitious accounts of all sorts of natural phenomena, including, of course, birds.

Sonnerat gave us, for example, the first image and description of the bird Scopoli would later name Columba luzonica, the Luzon Bleeding-heart: “it looks as if,” he rather vividly writes, this snow-white pigeon

had been stabbed with a knife and its own blood stained the feathers around the wound.

He was equally impressed by the kingfishers of the Asian tropics (“Europe,” he notes,”I believe has only one species”). His account of the family’s dining habits reflects some close observation and considerable admiration for these birds:

They all live from fish, which they capture by diving rapidly from the branches where they wait until some fish appear at the surface of the water; whereupon the kingfisher drops with precision onto its prey and seizes it in its beak without letting any other part of its body so much as touch the water…. If by chance a perched kingfisher drops its fish from the branch, it is so quick in its movements that it can catch its prey again before it falls any great distance. There are no other birds so fast of flight, so rapid of movement, or so keen of vision.

Sonnerat’s observations on the puzzling distribution of parrots leads him to meditate on island zoogeography:

While on the Asian continent one finds the same species spread across great distances and covering a very wide range, each of the islands where one finds parrots harbors one or more species that are unique to it and not found on other islands even in the same archipelago, however short the distance from one to the other. But it is not as if these birds were sluggish or capable of only brief flights…. And how is it, moreover, that when the archipelagos were formed, which can only be parts of the continent torn off and separated by revolutionary events, and when the islands of which they are composed were separated one from the other, there were not at the moment of revolution individuals of a single species scattered throughout the areas that would form those separate islands? Should we say that those species perished in certain areas but survived in certain others? What possible support could there be for such an assertion? Should we look to the influence of the climate or food? Those two conditions are not and cannot be sufficiently different in areas so close to each other, sharing the same sky and the same fruits, as to produce the changes and alterations that one would have to attribute to them. There must be another explanation, but I leave the question to the debates of other naturalists….

In the case of some species, Sonnerat was of a decidedly practical bent. Noting that the Secretarybird, in spite of its chicken-like bill, happily hunted rats, he suggested that

it could be useful in our colonies, and would probably not be difficult to breed there.

In 1790, Sonnerat was named Commander of Yanaon, in French India; three years later, that city fell to the British, and Sonnerat was imprisoned in Madras. He was not released until 1813, when he returned to France — only to die on his return to Paris on the last day of March 1814.

Today, Sonnerat lives on in the scientific names given to the Greater Green Leafbird, the Banded Bay Cuckoo, and the Gray Junglefowl. His reputation has suffered as errors and outright fabrications have been discovered in his works: the Secretarybird, for instance, could not have come from anywhere near the Philippines, and that notorious Kookaburra — which Sonnerat claimed to have discovered in New Guinea — is now thought to have been based on a stuffed bird given to him by Joseph Banks.

But as Denys Lombard put it in the Bulletin de l’Ecole française d’Extrême-Orient,

The fact that Sonnerat was not an objective observer, sometimes even unscrupulous, hardly matters in the end…. [He was active] on the dividing line between two worlds, motivated by the desire for scientific discovery and anxious to join the learned societies of London and Paris, but at the same time pragmatic and eager for conquest.

As such, Sonnerat was a characteristic figure of his time, and one well worth remembering, at least once a year.

They’re irresistibly photogenic, and this time around, last week in Nebraska, I happened to recall that my little point-and-shoot camera-for-dummies takes video, too.

Ladies and gentlemen, the Greater Prairie-Chicken:

Just click to watch a couple of birds display. And turn up the volume on your computer, too; nothing says spring on the Great Plains like that moaning and howling and cackling.

If variety is the spice of life, then the Great Plains in spring is the habanero chili of birding. In the short week my congenial WINGS group spent in Nebraska, we watched Tufted Titmice and Ferruginous Hawks, Blue Jays and Baird’s Sandpipers, Great-tailed Grackles and Pileated Woodpeckers—a mix of species tough to duplicate anywhere else.

As we’ve come to expect on this tour, the mammals were similarly diverse. The abundant white-tailed deer of eastern Nebraska were replaced in the Sandhills by a roadside herd of mule deer, and the eastern gray squirrels of Fontenelle Forest—their population increasing every year—contrasted neatly with the prairie dog towns of North Platte.

The weather, too, kept us guessing in the best prairie tradition. The week was cool to chilly on the whole, but the threatened snow never materialized, and it was dry up until the very last minute of the tour, when a light mist finally broke out into a much-needed rain. The notorious Midwestern winds held off, too, with the notable exception of our last afternoon together, when the drive back to the woodlands and wetlands of the Missouri River was made almost more adventurous than hoped by a fresh gale and poor visibility. But good company, good spirits, and good birds made even that inconvenience into nothing more than a trifle.

Our first nights’ lodging in Carter Lake is well situated indeed, and we started the tour with some first-rate waterfowl watching just five minutes from our motel. The eighteen species of ducks and geese on Carter Lake gave excellent views—to us and to a birdwatcher of another kind, a fine female Merlin, the first “good” bird of the tour.

A quick stop at Gun Club Marsh, south of Bellevue, produced the week’s rarest birds, an apparent hybrid drake Mallard x American Black Duck and his visually “pure” American Black Duck consort. The drake showed a bit of green on the forecrown and noticeably pale outer rectrices; as rare as black ducks are in the state in recent decades, obvious hybrids seem to be even scarcer.

We deserved a good meal after that, and La Mesa, one of the area’s best Mexican restaurants provided exactly that. Unfortunately, while we relished our supper, the evening breeze strengthened, and our old faithful American Woodcocks at Lake Manawa stubbornly refused to display during the half hour we listened to them buzz. No matter: we would have another chance the next evening, when the performance more than made up for our first attempt’s disappointment, four or five birds landing in front of us and dancing in the sky above our heads.

Sunrise the next morning found us in one of eastern Nebraska’s premier birding localities, the lowland forests and marshes of Fontenelle Forest.

The woodpecker show was especially good, with double-digit counts of Red-headeds and no fewer than three Pileated Woodpeckers, that latter species one of the great success stories after its total absence from the state for most of the last century.

A Barred Owl greeted us with its questioning “Whoo,” then sat at close range to let us admire it just off the trail; more surprising was a Great Horned Owl a bit farther on, perching nearby at the top of a tall cottonwood, then, when we had moved a short distance down the trail, flying into a cavity that almost certainly sheltered its eggs or young.

Among the Red-tailed Hawks was a stunning Krider’s Hawk, bright white beneath with clear wing linings and a white head marked only with chocolate lateral throat stripes; this is a locally common wintering bird in the state, but most are long gone by the end of March.

Our first runza lunch met with enthusiastic approval, and we were in good spirits as we head south and into Cass County. The familiar waterfowl spots harbored large numbers of ducks, and Eastern Bluebirds outblued the clear sky along the country roads. Our best stop by far was Platte River State Park, where a pair of Barred Owls duetted across the creek while an invisible Carolina Wren provided the obbligato.

American Robins and Cedar Waxwings bathed in the fast-flowing water; nearby were a Myrtle Warbler and a Ruby-crowned Kinglet, both rare winterers or, just possibly, early arrivals.

Schramm State Park, back on the north side of the river, was the site of our first Oregon Juncos and Harris’s Sparrows, feeding beneath the windows at the visitor center. Red-tailed Hawks were common and conspicuous all day, and a beautiful “intermediate” morph bird perched just above the van drew more oohs and more aahs than just about anything else all day—and rightly so.

The evening was clear and warm, and the wind died as we dined; our decision to return to Lake Manawa to give the American Woodcocks a second chance paid off well, with much dancing in the sky.

Temperatures rose through the night, and it was nearly up to freezing when we set off the next morning. We drove an hour west to the saline marshes of the Ceresco Flats, where Ring-necked Pheasants honked and a large flock of Snow Geese cackled and barked. Song and American Tree Sparrows lined the deserted roads, joined by more Harris’s Sparrows and a scarce Swamp Sparrow. A distant singing Eastern Meadowlark was the only one we tallied all week; Western Meadowlarks were already arriving by the hundreds, but Easterns are typically more hesitant, waiting to occupy their restricted Nebraska breeding grounds until spring has well and truly sprung.

The first Sandhill Cranes welcomed us to Grand Island, where we had time before lunch to scan the flocks at Mormon Island and to give serious study to the couple of hundred Richardson’s Cackling Geese on the moat of the Stuhr Museum. After a brief stop at the Crane Meadows feeders to admire the Oregon, Cassiar, and Slate-colored Juncos, we slowly made our way west to Kearney past fields packed with Sandhill Cranes in their untold thousands. We checked in to our hotel, enjoyed a steak dinner, and repaired to the Gibbon Bridge for the evening show.

It doesn’t matter how often you’ve seen the cranes come to roost: the experience is always uniquely moving, beautiful and wild and noisy like nothing else on the continent. Tens of thousands of birds eventually settled into the river’s shallows, and I suspect that I was not alone in hearing the echoes of their roar long after my head had hit the pillow for the night.

If anything, the morning flight was even more spectacular this time. The rattling of the flock was audible as we stepped out of the car, but it became deafening when, just before sunrise, a Bald Eagle flew low over the river, setting off a noisy panic that lasted for several minutes as flocks rose and swirled and shouted over the deck where we stood in wonder. Three quarters of an amazing hour later, most of the birds had left their river roost for the fields, and it was time for our breakfast, too.

An hour after leaving Kearney, we were in the Sandhills, one of the most beautiful and least densely populated landscapes in the country. Rough-legged Hawks joined the abundant red-tails to hunt the roadsides, and yuccas replaced the red cedars of the tallgrass prairie. We arrived in Broken Bow, the largest city in the hills, in good time, and wended our way to the sewage ponds for a little pre-lunchtime birding.

So productive in some years, the ponds and neighboring creekbed were almost disappointing this time. Only almost, though, as on our way out we spotted two brown spots on the icy rim: Baird’s Sandpipers, the first of the huge numbers of that neotropical migrant that will move through the central Great Plains in April and May. Docile by nature, or maybe just exhausted by the long flight from the Andes, these two let us approach to within just a few dozen yards for lingering scope views of their long wings, spangled golden upperparts, and odd slender bills.

Lunch at the Tumbleweed Café was as good as ever, the high quality of the food rivaled by the friendly good nature of our fellow diners. We were a content group of birders as we drove the last hundred miles to Mullen, in the very heart of the Sandhills.

We took advantage of the time change to put our feet up for a little while, then met Mitch for the twenty-five-minute ride out to the lek of the Greater Prairie-chickens. While we waited for the main event, Rough-legged and two Ferruginous Hawks—one of the latter a dramatic dark bird—patrolled the hills outside our blind, and two coyotes sniffed their way along the distance fence line in search of whom they might devour.

Two prairie-chickens arrived soon after we did, but uncharacteristically, the bulk of the flock waited until less than an hour before sunset to fly in and start to display. Eventually we had twenty males on the lek in front of us, at times no more than fifteen yards away, booming and strutting and stamping their feet at each other. The late afternoon light turned golden, then pink, and still the birds danced. We were a silent lot when we turned to drive back to town, impressed and honored to have witnessed a ritual that dates back beyond human memory.

Dinner in Mullen restored us nicely, and we were all bright and chipper when 5:30 rolled around the next morning and it was time to visit the other grassland grouse on their own dancing ground.

The Sharp-tailed Grouse were more punctual than their cousins of the evening before, and five males were whirring and cackling on the pasture in front of us by the time the sun rose over the Sandhills. No hens arrived to admire the males’ manic exertions, so they paused in their display at 8:00, giving us a chance to slip unseen back into our shuttle and return to Mullen for a lavish breakfast of pancakes, waffles, eggs, and cup after cup of good hot coffee.

We returned to the motel to clean up, pack, and bid farewell to our hosts, then drove straight south through the hills to North Platte. We paused on the way to move the carcass of a white-tailed jackrabbit from the road—in hopes that the Ferruginous Hawk we’d flushed from it would not wind up in the same sad state.

It was delightfully warm and bright when we arrived at North Platte’s Cody Park.

As usual in the early spring, a large flock of waterfowl—some injured, most simply spoiled by the park-goers’ generosity with corn and birdseed—lingered on the pond, and we took full advantage of the chance to watch five species of geese at arm’s length. Richardson’s Cackling Geese were the most common, but the tiny Ross’s Goose was everyone’s favorite.

Soon, though, runzas called, and we enjoyed a leisurely lunch before striking out on the four-hour drive east to Omaha.

It should have been four hours, but the south wind, so welcome just a couple of hours before, increased rapidly, violently, such that great clouds of dust and debris obscured vision and slowed traffic; higher-profile vehicles than ours were in the ditches, and even our van required more concentration than usual. With the entire afternoon ahead of us, we took our time, stopping to bird and to refuel more frequently than usual and pulling in, safe and sound, to our hotel on the banks of Carter Lake with plenty of time to enjoy a final festive dinner together.

Next morning we found that the wind had brought warm temperatures, a light mist, and. most importantly, some migrants. A brief walk along Bellevue’s Trader’s Trail turned up a Red Fox Sparrow, and Turkey Vultures floated low in the dim skies as we drove across the Missouri to Lake Manawa. Ducks and gulls were abundant on the lake, and a distant drift of white on the far shore resolved itself into the spring’s first flock of American White Pelicans, 75 huge birds tucked into the shallows after their flight from the south. As we made our way towards the airport and the end of the tour, a dark blob in a cottonwood above the road turned into a Merlin, a fitting bookend to a week that had started with that species and included so many more—many more birds, yes, but many more experiences, too, and many happy moments in congenial company.

Want to join us next year? Drop in at the WINGS website and sign up!

March 26, 1870, that is.

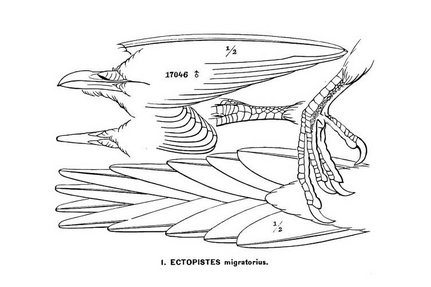

In the case of Robert Ridgway, we happen to know. The nineteen-year-old illustrator was in Washington, and he spent that morning in a visit to the city’s market, where he purchased fresh male specimens of the Passenger Pigeon.

The birds’ irides, he would later write, were

scarlet or scarlet-vermilion; bare orbital space livid flesh color; legs and feet lake-red, or pinkish-red…. Now extinct.