More than 1200 pages in to his massive completion of the Abbé Bonnaterre’s Tableau encyclopédique et méthodique, Louis Pierre Vieillot offers an account of the bird he calls the “buse cendrée,” Falco cinereus, known to English speakers today as the northern harrier. His description of the bird, occupying slightly less than a column of text, is an expanded version of the terse entry prepared fifteen years earlier for the Histoire naturelle des oiseaux de l’Amérique septentrionale.

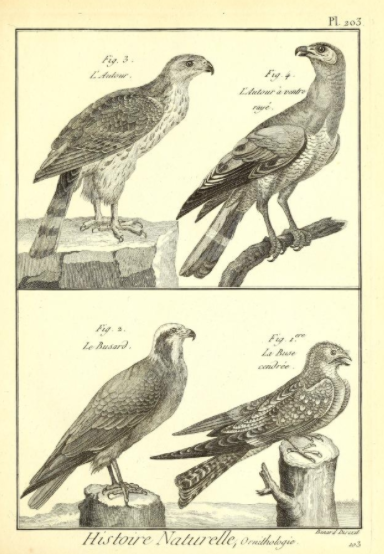

The Histoire naturelle had not illustrated this species, a miss made up for in the Tableau, where, the author tells us, we can find the harrier’s portrait on Plate 203. And there it is, as promised, Figure 1 in the lower right-hand corner.

But wait. Something seems not quite right.

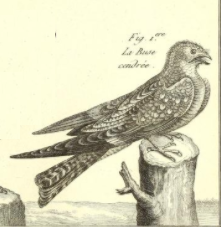

With its short, hooked bill menacingly agape, I suppose the bird looks suitably predatory, but no amount of squinting and good will can turn it into a harrier. Instead, this is only too clearly a nighthawk.

Vieillot knew the common nighthawk, sort of. Like most of his predecessors in the North American field, he confused it with the continent’s other goatsucker species, and even as late as 1823, when the Tableau appeared, he seems not to have known that Alexander Wilson had managed to sort them all out a decade and a half before.

None of that, however, explains how the nighthawk came to masquerade under the name of the buse cendrée. Might there be a clue in the signature on the plate?

Rather than the usual “delineavit,” “drew,” or “sculpsit,” “engraved,” here we have a notice that the plate was prepared under the supervision of the prolific engraver Robert Bénard. A suspicion begins to form, one confirmed by a comment Vieillot makes in his introduction to the effect that the figures in the Tableau are not original but rather reproduced from other sources.

Vieillot says nothing about just how the originals were collected, and by whom, and how they were copied, and by whom. But he does warn his reader that “some of the bird engravings are incorrectly placed,” a wry understatement if he was referring in part to our harrier/nighthawk.

The text is not without its own problems, either. Two of the three citations at the end of Vieillot’s account of the buse cendrée are, at best, misleading: the reference to Brisson is to the 1763 Latin edition rather than, as expected, the 1760 bilingual original; and the page number given for the account in Buffon’s Histoire naturelle is off by a whopping 133.

The reference to George Edwards, on the other hand, is right on. Page 53 in his Natural History of Birds indeed describes the ash-colored buzzard, though in terms so general as to make it impossible to tell whether his bird is a goshawk, a buteo, or a harrier.

The bird on the accompanying plate, drawn, etched, and colored by Edwards himself, is only slightly more identifiable, more closely resembling a gyrfalcon than any harrier. In any event, Edwards’s Plate 53, the explicit citation in the Tableau notwithstanding, cannot possibly have provided the exemplar for the buse cendrée.

Leaf through a few pages in Edwards, though, and we come to his Plate 63, depicting “the whip-poor-will, or lesser goat-sucker.” The description, as expected in the mid-eighteenth century, conflates at least two species of nocturnal birds, but the plate is what’s important here.

This, one of Edwards’s more appealing works, is unmistakably the source of the engraving in the Tableau. The extreme faithfulness with which it was copied–the number of visible toes, the misplaced tertial, the exact shape of the tail tip and open bill–suggests that Bénard and his artists had recourse to the camera lucida or a similar optical device when they reproduced their exemplars.

My guess is that when Bénard direxit his staff to prepare an illustration to accompany Vieillot’s buse cendrée, he gave them the wrong plate number in Edwards, namely, 63 rather than 53; or that whoever was charged with the copying made the mistake on their own. Soixante-trois, cinquante-trois: it was easy to be off by ten. And Edwards’s nighthawk, with those long wings and short, curved bill, was sufficiently hawk-like as to raise no alarms for the engraver who copied it as a harrier.

It’s a vanishingly small detail, but in combination with the garbled citations in Vieillot’s Tableau entry, a heartening reminder to the rest of us mortals that even Homer nods–and that book production has always been as difficult as it is complex.