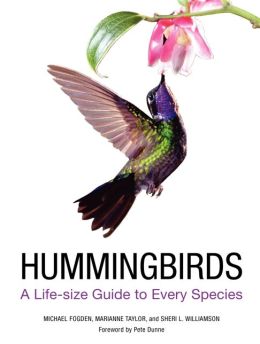

What an appealing idea: a guide to all of the world’s more than 300 hummingbirds, each species illustrated with full-size images from the camera of a highly talented photographer. I couldn’t wait.

There is a long history of richly illustrated books devoted to the family Trochilidae, culminating in the early and mid-nineteenth century with the splendid volumes produced by Audebert and Gould. Those and other artists developed complicated, often expensive techniques for depicting the shimmering plumages of their tiny subjects; the results were books that still rank high on the most-desirable lists of birders and bibliophiles alike.

If our ancestors could create such beauty with gold leaf and oils, the miracle that is digital photography should make even more stunning images available to us moderns — maybe even for a sum considerably less than what one pays for a house in the New Jersey suburbs. And Michael Fogden would be the one to do it. A zoologist and professional freelance photographer, Fogden has produced some spectacular images, among them the photos in his and Patricia Fogden’s lovely Hummingbirds of Costa Rica.

I don’t doubt that many of the photographs used for Fogden’s new book started out every bit as fine, but their treatment at the hands of the photographers and designers responsible for Hummingbirds has rendered a significant number of them unappealing at best.

The full-page frontispiece and the illustrations accompanying Sheri L. Williamson’s informative introduction do show Fogden’s work to advantage, sharply reproduced images of almost inconceivably bright birds in their habitats, bathing, feeding, and rearing young. In unfortunate contrast, the birds in the individual species photos have been digitally “cut out” from their background, left to float against the white page with the odd (and equally isolated) flower or twig. Many of the images in my review copy are blurry –the whole bird, not just those humming, buzzing wings. Birders might forgive this, but the book’s audience seems rather to be casual hummingbirders, a different species entirely, and they are likely to be disappointed that Hummingbirds so often fails to rise to the level of graphic beauty regularly attained even in popular magazines.

A more serious objection for the birder is that no species is represented by more than two portraits, and the vast majority make do with just one. Predictably, it is almost always the flashy male whose image makes the cut, but for a few species only the female is shown. I was taken aback on finding the Spangled and Frilled Coquettes, for example, depicted only as badly blurry females; surely it would have been worth including the spectacularly adorned males of those species or of the Glittering-bellied Emerald, whose names are here belied by the images.

Birders in search of a comprehensive collection, however sexually skewed, of hummingbird photographs will also be surprised that this “Life-size Guide to Every Species” fails to illustrate more than seventy of those species. Many of these birds are rare and little known — at least one of them, indeed, extinct — but it is a strange surprise to discover, for example, the Plain-capped Starthroat and the White-tailed Sabrewing accorded only textual treatment here: the starthroat is common and familiar in its range, the sabrewing scarcer but still readily found, at least on Tobago. Handsome photographs of both, and of many of the other species not illustrated in Hummingbirds, are just a google search away.

All of the world’s hummingbird species, including those without photographs, are concisely described in the text. A brief physical description is typically followed by a note on behavior — usually feeding behavior — and a summary of the species’ apparent conservation status. These species accounts are on the whole clear and accurate, though they do reveal some unfamiliarity with the ranges of the northernmost hummingbird species. There is no indication in the text or in the accompanying map, for example, that the Berylline Hummingbird occurs annually in the US Southwest and has bred there on several occasions. For the Xantus’s Hummingbird, the text records “occasional” occurrences in California, but neglects to mention the startling record from British Columbia, a lone stray that was almost certainly ogled by more humans than any other of its species ever.

The species accounts are presented in the phylogenetic sequence put forth in the latest edition of the Howard and Moore list — except for the unillustrated species, which are grouped together in the back of the book. The difficulty of finding any particular bird in these 360 pages is exacerbated by the unhelpful index of English names, which follows the recent inexplicable trend of ordering the entries not by the “group” name but by the attributive; would anyone really think to look under “W” for the White-necked Jacobin?

The book concludes with two pages of bibliography. I am surprised to find under the heading “Key general titles” Meyer de Schauensee’s 1978 Venezuela field guide; I don’t have a copy at hand, but it’s hard to imagine that the hummingbird entries there are better than those in Steve Hilty’s volume from the same publisher, issued a quarter of a century later. Surprise yields to disappointment on seeing Steve Howell’s Hummingbirds of North America not mentioned at all, an inscrutable omission. The remainder of the bibliography, under the rubric “Other useful articles and books,” is so eclectic as to seem randomly assembled.

Ultimately, this volume will satisfy no one who comes to it with hopes sharpened by encounters with the older trochilidist literature or with the birds themselves. The vast number of backyard hummingbirders, interested in flashy photos and purdy birdies, will find many of the images here uninspiring, and birders, in search of new information on identification, life history, or conservation, will come away as hungry as they approached.

What to do? We can start saving our dollars to buy the relevant volume of the Handbook of Birds of the World — or, if you’re poor like me, consult the Internet Bird Collection, where there are photographs (and often video and audio, too) of 309 species of hummingbirds. Maybe the web is after all the true successor to the great hummingbird books of centuries past.