It’s comforting to think that once an object enters the collections of a major museum it’s safe, preserved for all time and all people.

Comforting. And false.

Museums and libraries, private and public, buy and sell and trade items from their holdings all the time, for all sorts of reasons. This coming April, the Indiana Historical Society will auction its copies of Audubon‘s Birds of America, along with the Viviparous Quadrupeds, purchased eighty years ago for the then princely sum of $4,000. The proceeds from the sale will be used to enrich the Society’s collections of books, papers, and artifacts more immediately connected to the history of Indiana.

Thus far, the Society’s president, John Herbst, appears to have succeeded in forestalling the (often irrational) outcry that usually follows the announcement that a collection will be de-accessioning a prominent object:

The revenue should further the historical society’s modern mission of focusing on Indiana artifacts. The society would have loved to have had the money to buy a 1961 letter penned by Indiana native Gus Grissom during a recent auction, but the item — which alluded to the competition among Mercury 7 astronauts — slipped away. The same goes for a letter written by a Civil War soldier from Indiana, who was part of the 28th Regiment, United States Colored Troops.

“We continually see Indiana-specific items on the market that we’d like to have,” Herbst said.

Much of Audubon’s work — and particularly his masterpiece, “The Birds of America” — is publicly available through the thousands of prints, posters and cards that have been made, Herbst said. And there’s another original [copy] of that book at the Indiana University Library in Bloomington.

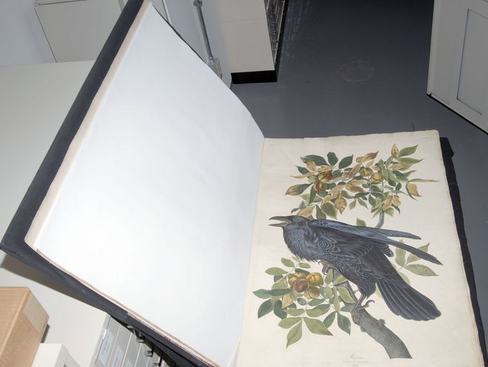

And besides that, the IHS’s Birds and Mammals are both said to be in noticeably worn condition, after

years spent on the shelves of the Borden Institute, a private school in what was then called New Providence, Indiana. “They still are vivid colors, and there’s a lot of wonderful attributes that they still have,” Herbst said. “But they were materials that were in public libraries before we got them. They both had a lot of use before the society purchased them.”

As a result, Sotheby’s has set a modest reserve of only (only!) three million dollars for the Birds. If memory serves, the most recent complete sets of the Birds have brought three times that or more at auction. Somebody’s going to get a real bargain.

Given the poor-quality binding and the apparent rough condition of the plates, there would be nothing but sentiment to prevent that lucky purchaser from breaking the set up and selling the images singly, the fate of so many copies of this iconic book over the years.

With that prospect in mind, I hope that Sotheby’s and the Indiana Historical Society will make the effort to thoroughly document whatever signs of use are present on the plates. A pristine set of Audubons is a fine thing, but how much more valuable — intellectually, not financially — would be a copy, its binding shaken and its edges smudged, with the notes and arrows and marginal sketches of an early owner or user. I want to know what the boys and girls of the Borden Institute thought about this book, how they viewed it and what it meant to them. After all, what else are old books good for?