It’s Christmas in July for most birders with the appearance of the now-annual Supplement to the AOU Check-list. This year, as always, Santa Claus giveth and Santa Claus taketh away. On balance, those who care about numbers will find their lists increasing. For the rest of us — for most of us — the yearly update is a chance to look into the workings of taxonomists and ornithologists as they toil to decipher the relationships among our birds.

The greatest loss for listers is certainly that handsome gull “kind” known over the past 45 years as the Thayer gull. Jon Dunn and Van Remsen argued cogently, even devastatingly, that the research supporting full species status for the bird was thoroughly flawed, and that the “burden of proof” should be on those asserting its distinctness from the Iceland gull. To my memory, Dunn and Remsen’s is the only taxonomic proposal ever considered by the AOS committee to use the phrases “scientific misconduct.” The authors encourage further research into the taxonomy of the large herring-like gulls, but meanwhile, thayeri is reduced to a mere synonym.

Some birders will probably be disappointed, too, by the committee’s having declined to accept a number of proposed splits and re-splits, some involving some of the most familiar birds on the continent. The willet remains a single species, as does the yellow-rumped warbler.

The eastern and western populations of the brown creeper, the Nashville warbler, and the Bell vireo were also sentenced to continued cohabitation.

But there are splits aplenty, too.

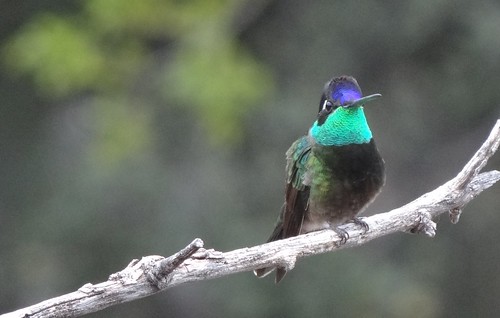

The gorgeous little Baird junco gets its own box on the ticklist again, and the Talamanca hummingbird of Costa Rica and Panama is once again treated as distinct from the northerly Rivoli hummingbird.

To my surprise, we also have a new crossbill species in North America. The Cassia crossbill (the English name commemorates the type locality, and is far better than the cutesy scientific name sinesciuris) breeds in the South Hills and Albion Mountains of Idaho. It is apparently sedentary, making identification perhaps a bit easier; the bird is said to be larger than other sympatric crossbills, and to have different calls and songs.

My surprise has nothing to do with the quality of the research establishing this as a distinct species: all this genetics stuff is way beyond me. But I did not expect any real movement in crossbill classification to be inspired by one taxon; I’d thought the committee might wait for a universal solution to these difficult problems. In any case, Burley had better be ready for an ornitho-influx.

We also get a split in the “gray” shrike complex. The North American northern shrike is now considered specifically distinct from its Old World counterparts; its species epithet is once again borealis, the name given it by Vieillot in 1808.

Our northern harrier is also split from the hen harrier of Europe, under the Linnaean name Circus hudsonius. The name honors the employer of James Isham, who sent the first specimens to George Edwards in the 1740s.

The number of birders dreading the lump of the redpolls was almost as great as that of those devoutly wishing its consummation. The resolution (for now) leaves us with three species in the United States and Canada, the hoary, common, and lesser redpolls, that last listed as accidental. The Acanthis debate is certain to outlive us all.

Familiar at least as a target bird to observers in Middle America, the old Prevost ground sparrow is no more. In its place, we have the white-faced ground sparrow and the Cabanis ground sparrow, the former occupying a range from southern Mexico to Honduras and the latter restricted to Costa Rica’s Central and Turrialba Valleys. The two species differ conspicuously in head and breast pattern — conspicuously, that is, if you’re fortunate enough to get a good look at these often sneaky sparrows.

And speaking, inevitably, of sparrows, the American birds going under that slippery English label are now assigned to a family of their own, Passerellidae. In this, the AOS follows the recent practice of nearly all ornithologists over the past five years. It seems likely that the name will be replaced in the near future by Arremonidae, which if valid has nomenclatural priority.

The nine-primaried oscines — the “songbirds” at the back of the bird books — have also been rearranged, giving us all a new sequence to memorize. (I understand that the new sequence will be used in the seventh edition of the National Geographic guide, coming in a few weeks.) The most notable taxonomic change here is certainly the elevation of the yellow-breasted chat to its own family, Icteriidae, occupying a position in the linear sequence just before the orioles and blackbirds, Icteridae. This is just the latest stage on a classificatory journey sure to continue for a long, long time.

There will be more to say, no doubt, when the complete text of the supplement is readily available on line. Meanwhile, much to ponder.