Audubon’s famous Fork-tailed Flycatcher, collected in New Jersey in June 1832, gets all the press.

But that wasn’t the first fork-tail recorded in the US — or even, amazingly enough, the first for New Jersey.

Sometime before 1825 — the usual date in the secondary literature seems to be “around 1820,” while Boyle gives “around 1812” —

a beautiful male, in full plumage … was shot near Bridgetown, New-Jersey, at the extraordinary season of the first week in December, and was presented by Mr. J. Woodcraft, of that town, to Mr. Titian Peale, who favoured me with the opportunity of examining it.

“Me,” of course, is Charles Lucian Bonaparte, writing in his American Ornithology, for which Peale also provided the rather stiffly elegant plate reproduced above.

When James Bond set out, almost 75 years ago now, to determine the subspecific identity of US Fork-tailed Flycatchers, he was unable to locate any of the specimens taken before 1834, “if any exist.” But even absent a skin, Bonaparte’s detailed description of the Bridgeton bird allows us to pin it down almost 200 years later:

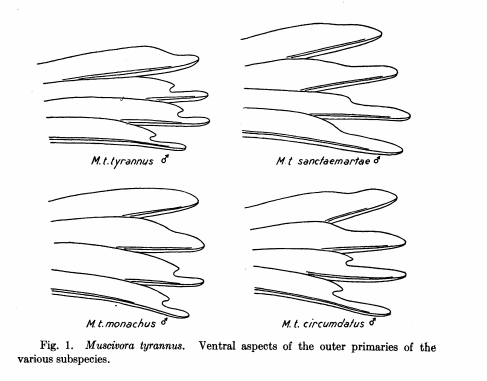

… the three outer [primaries] have a very extraordinary and profound sinus or notch on their inner webs, near the tip, so as to terminate in a slender process.

That is enough, according to Zimmer, to identify the Woodcraft specimen as a member of the subspecies savana (then known as tyrannus).

That austral migrant, abundant in its range, is responsible for almost all northerly records of this species, though Zimmer identified one New Jersey specimen, of unknown date and locality, as sanctaemartae (a determination adjudged only “possible” by Pyle).

To Bonaparte, it was “evident” that his specimen “must have strayed from its native country under the influence of extraordinary circumstances.”

That’s for sure.