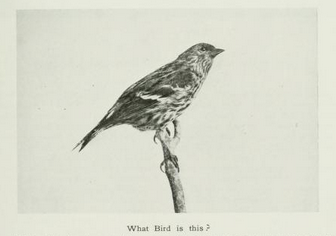

As predicted, this Pine Siskin didn’t pose too many problems for most of us, and the responses tallied pretty much all of the classic “field marks,” including the pointed bill, the small head, the fine black streaking, and the wing markings.

The major “confusion species” for this bird, especially since the 1940s, is the House Finch, females and juvenile males of which are also brown and streaked and fond of bird feeders. There are differences, of course, most of them covered by the respondents to the quiz — the most important, though, unmentioned.

A House Finch, bits of which are visible in the photo above, is a long-tailed, short-winged bird, with the primaries protruding just a short distance beyond the tertials and the wing tip often barely seeming to extend down the tail at all.

Contrast that with the very different rear end of a Pine Siskin:

The long, long primaries of this bird create a noticeably attenuated wing tip extending far beyond the tertials, and that sharp little tail seems barely an afterthought. This is the structural difference that strikes me every time, from any distance, before I can gauge the head size or the bill shape or the wing pattern or the width of the shaft streaks on the underparts.

Over most of the continent, it hasn’t been much of a finch winter. But maybe next year will find more of them at our feeders — and maybe the reminder to start at the rear will make them easier to identify.