In 1912, Harry C. Oberholser set out to sweep the Augean stables of green heron taxonomy,

to clear away, as far as the present material will permit, the confusion now existing with regard to the relationship and distribution of the various races… with their intricate relationships and rather peculiar geographical distribution.

Of the eighteen subspecies Oberholser claimed to be able to distinguish, only four have stood the test of time: bahamensis from the eponymous islands; frazari from southern Baja; anthonyi of western North America; and the nominate virescens of eastern North America and middle America south to Panama.

Oberholser’s splittery may belong to the past, but one conclusion reached in his revision still rests its dead hand heavy on the list of American birds.

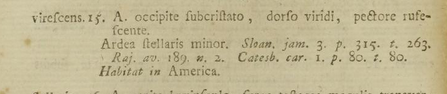

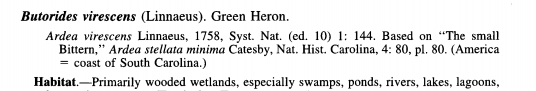

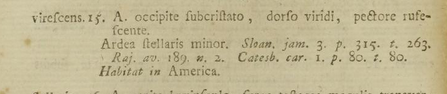

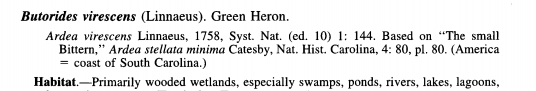

We owe the standard scientific binomial of the green heron to Linnaeus himself, whose Ardea virescens appeared in the Systema naturae of 1758, the first edition to “count” in zoological taxonomy.

It’s a good description:

a heron with a somewhat crested rear crown, a green back, a rusty breast….

The Linnaean statement of range at first strikes us as a bit vague: this bird “lives in America.” But it makes sense if we look at the ornithological sources on which Linnaeus based the name.

Mark Catesby had recorded the bird in Carolina and Virginia, while Hans Sloane and John Ray had prepared their descriptions — the former English, the latter Latin — from a specimen taken, it would appear, in the West Indies.

“Habitat in America” seems a reasonable way to describe the composite range of so widespread a bird.

Oberholser, however, knows better.

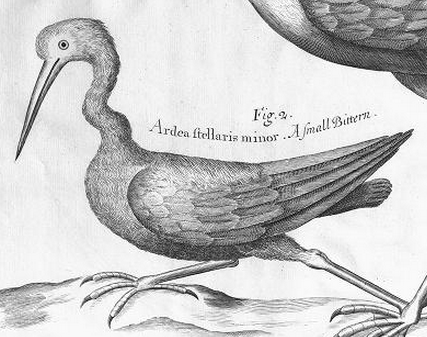

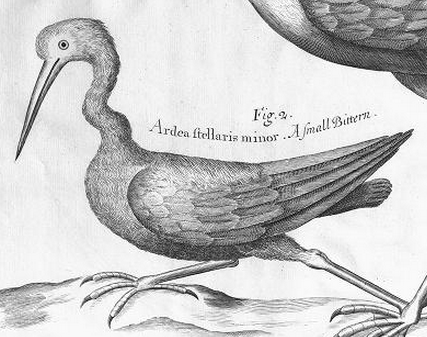

In his 1912 revision, he writes that “Linnaeus’s diagnosis fits only the green heron,” as do, obviously, Catesby’s text and plate. But Ray and Sloane, on the other hand, “without much doubt” in fact recorded not the green heron but the least bittern.

Oberholser concludes that

This makes Catesby’s description the sole basis of [Linnaeus’s] name, and since most of his [Catesby’s] birds came from the coast of South Carolina, it seems best to restrict the type-locality to that region,

thereby excluding Sloane’s and Ray’s contributions to the Linnaean project.

Oberholser’s restriction is still treated as authoritative in the latest edition of the AOU Check-list:

But was the bird described by Ray and by Sloane really what we know today as a least bittern?

Both those authors describe the bird, apparently a specimen dissected by Sloane on his tour of the West Indies, as “fourteen Inches long from the point of its Bill to the end of the Tail,” with a wing span of about 20 inches — a bit on the small side for a green heron, but largish for a least bittern. Critically, neither remarks on the whitish or tawny panels so conspicuous on the spread wing of the least bittern, but they do note that the wings have “some whitish and tawny Spots here and there,” as in a non-adult green heron. None of the bittern’s distinctive wing and back pattern is apparent in Sloane’s illustration.

Oberholser’s characteristic confidence notwithstanding, there is no reason not to believe, with Linnaeus, that Ray and Sloane were both describing the bird we know as the green heron. Thus, the limitation of Linnaeus’s sources to Catesby and the consequent restriction of the type locality to coastal South Carolina (which Oberholser had already managed to sneak into the 1910 edition of the Check-list) is, if not wrong, then at the very least unnecessary. I say we should give Sloane and Ray their due, too.

Ardea virescens Linnaeus, 1758, Syst. Nat. (ed. 10) 1:144. Based on “A small Bittern,” Ardea stellaris minor Ray, Syn. meth. avium, 1: 189.4; on “The small Bittern” Ardea stellaris minor Sloane, Voy. Isl. 2: 315; and on “The small Bittern,” Ardea stellata minima Catesby, Nat. Hist. Carolina 4: 80, pl. 80. (America = West Indies and Virginia and South Carolina.)