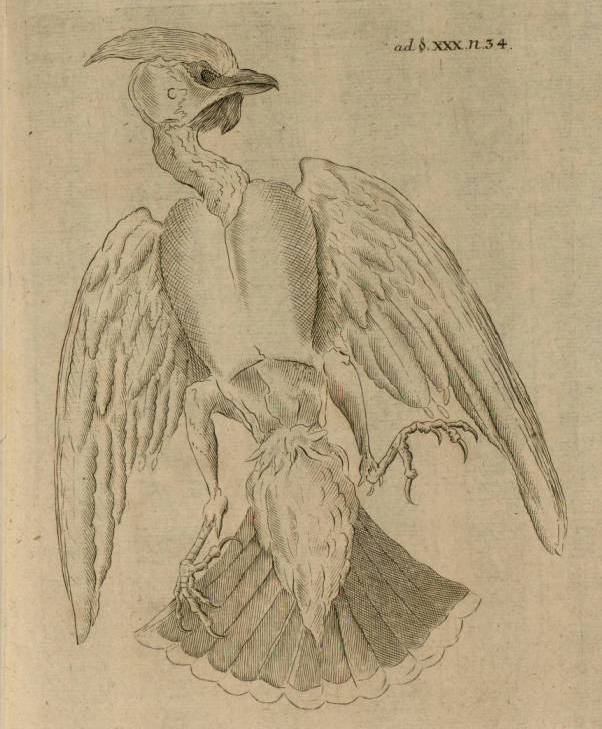

We’re happily, gratefully spoiled. Need a note from an obscure regional journal published half a century ago? One e-mail, and the text is on my computer desktop within minutes. Wonder what the type specimen of a bird looked like? I can see it in three dimensions on the museum’s website. Want the original account of a species’ discovery? It’s right there in my e-bookmarks. All pretty miraculous.

Sometimes, though, I’m surprised at how quickly information and objects could move even a century and a half ago. The beautiful and relatively uncommon Lawrence’s goldfinch offers an example.

John Graham Bell, Audubon’s companion on the Missouri and Theodore Roosevelt’s mentor in the taxidermy shop, first encountered this pretty little finch in Sonoma, California. He deposited his specimens in Philadelphia, where John Cassin published a formal description of the species in 1852.

Cassin named the bird

in honor of Mr. George N. Lawrence, of the city of New York, a gentleman whose acquirements, especially in American Ornithology, entitle him to a high rank amongst naturalists, and for whom I have a particular respect, because, like myself, in the limited leisure allowed by the vexations and discouragements of commercial life, he is devoted to the more grateful pursuits of natural history.

(Lest there be any worry that Cassin had slighted Bell, in the same paper the Philadelphia ornithologist named the pretty California sage sparrow still — again — known as Bell’s.)

Not much more than a year later, in mid-December of 1853, Charles Bonaparte was able to introduce the bird to his colleagues in Paris, in a letter describing the specimens brought back from the New World by Pierre Adolphe Delattre:

Our collection dazzles especially in the finches…. One… now appears for the first time in Europe, the pretty Lawrence’s goldfinch, discovered by Mr. Cassin in Texas and collected by Mr. Delattre in California.

As usual, Bonaparte could not resist going on to re-describe the species, but this time at least he preserved Cassin’s scientific name.

Bonaparte’s misidentification of the discoverer — it was Bell, not Cassin — and of the type locality — it was California, not Texas — suggests to me that he had not yet actually read the description published the year before. Then as now, though, news traveled quickly along the ornithological grapevine.

Just not yet at the speed of light.