In 1751, George Edwards’s “generous encourager” Mrs. Clayton, of Flower in Surrey, seems to have engaged the painter and ornithologist to record the birds of her aviary. It was not an unusual request: Edwards tells us that by then he had

been for a good part of the Time employ’d by many curious Gentlemen in London to draw such rare foreign birds as they were possess’d of…. as the like Birds might perhaps never be met with again.

With the permission of his subjects’ owners, Edwards

never neglected to take Draughts of them … for [his] own Collection

as well, and it was those drawings that he published — though he was “backward in resolving to do it” — in the Natural History of Birds and in the Gleanings.

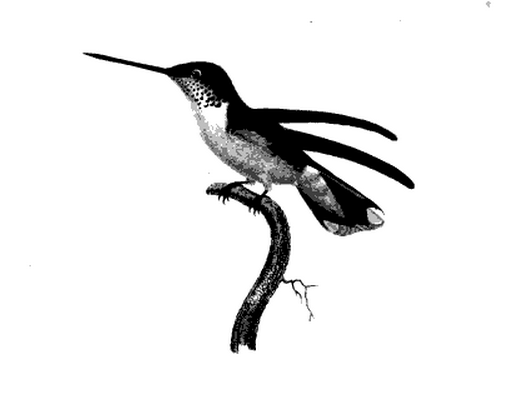

His visit to Flower turned up a number of birds new to him and to science, among them a curious passerine with

the bill white, the head and neck black: the back, wings, rump, and tail are of a blackish yellow-green, or dark olive colour: the breast, belly, thighs, and covert feathers under the tail, are of a yellow colour: the legs and feet are of a dusky colour…. Many of its feathers are curled….

Logically enough, he named it the black-and-yellow frizzled sparrow.

As complete as his description was and as precise as his engraving, though, there was one thing Edwards could not say with any confidence about Mrs. Clayton’s sparrows:

they are natives either of Angola or the Brasils, but I cannot determine which.

It’s a good four thousand miles as the bunting flies between Luanda and Sao Paulo, but such wild uncertainty was simply par for the course in the world of eighteenth-century ornithology. In a similar context, Buffon himself, who was in a better position than most to determine the provenance of his specimens, noted with a sigh

that nothing is more imperfectly known than the native country of birds that come from a great distance and pass through many hands.

When Linnaeus named Mrs. Clayton’s bird Fringilla crispa (“curly-haired finch”), he settled, apparently arbitrarily, on Angola as the terra typica. Others, though, more careful bibliographers than the great Swede, left the matter undecided: Brisson says “in the kingdom of Angola or in Brazil,” and even Gmelin, in his 1789 edition of the Systema, returns to Edwards’s original formulation, “either Angola or Brazil.”

Why those two, so far-flung localities? Buffon fills us in on the “many hands” involved here:

As this bird came from Portugal, one concludes that it was sent from one of the chief colonial possessions of that country, namely, from the kingdom of Angola or from Brazil,

an explanation repeated a few years later by John Latham in his General Synopsis:

As we know it not except through Portugal, its native place is not certain.

By 1802, these birds were being imported into France. Louis-Pierre Vieillot owned a pair, but not even he could say where the species was native: Portugal, which remained reluctant to grant other Europeans direct access to its colonies, remained the only source. Twenty years later, Vieillot still did not know where his frizzle-feathered charges had come from.

That was bad enough. But gradually, the mystery shifted from the origin of the bird to its identity. Just what was Mrs. Clayton’s sparrow?

In hindsight, it’s obvious that the frizzled finch was a seedeater — and with that complete black hood, just as obviously a seedeater of Ridgely and Tudor’s Type II. But which one?

The identification and taxonomy of the Sporophila seedeaters is a tangle beyond compare. No synonymy agrees with any other, and certain of the specific epithets have seemed to float in space, available to anyone who cares to reach up and grab one to slap, more or less at random, onto a troublesome bird.

What we know today as the yellow-bellied seedeater has fallen victim to such haphazard naming more than once since it was first described by Vieillot in 1823. There’s no reason here to rehearse its onomastic fortunes and misfortunes, from gutturalis to olivaceoflava to nigricollis and forth and back and back and forth.

It’s enough to know that this species, widespread in the American tropics, including the former Portuguese possessions in Brazil, comes closest to Edwards’s frizzly finch.

I believe that it was Bowdler Sharpe who first sought to identify the mystery sparrow as this seedeater. In Volume 12 of the Catalogue, he adduces Edwards’s description and Linnaeus’s names first in the synonymy for Spermophila gutturalis — though in both cases with a hesitant question mark.

Far less cautious, Outram Bangs asserted outright that

Edwards’s plate agrees exactly in measurements and color with this species except that the yellow is a little too vivid.

Indeed, Bangs was so sure that Mrs. Clayton’s birds were yellow-bellied seedeaters that in 1930 he urged that Linnaeus’s name of 1766 — based on Edwards’s plate as “type” — be restored, such that the bird should henceforth be known as Sporophila crispa (Linné).

Charles Hellmayr disagreed. Vehemently. In the Catalogue of Birds of the Americas, Hellmayr does not even include Bangs’s Linnaean name in the synonymy, instead rejecting it in a snarl of a footnote:

I am, however, quite unable to recognize our bird in “The Black and Yellow Frizled Sparrow” … which formed the exclusive basis of Linné’s account. The bright yellow belly and the heavy, acutely pointed bill, which in shape, recalls that of a Siskin, render the identification more than problematical, and I hesitate to sacrifice a certainty for the benefit of an uncertainty.

And there, so far as I know, is where it stands. Debate about the frizzled sparrow fizzled seventy-five years ago with Hellmayr’s dismissal of the only plausible identification, and Mrs. Clayton’s bird is consigned to the dustheap of nonce species, forgeries, and incompetent errors.

It’s probably just a tanager anyway.

![Marsigli, whiskered [or black?] tern](http://birdaz.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/Screenshot-2014-09-14-13.28.48.png)