Yesterday morning’s visit to the Pont du Gard was a good one: we missed the one “easy” target we’ve always got before — the charming little yellow-patched Rock Sparrow — but we made up for it.

White Wagtails danced in the shallows, while the air was full of Crag Martins, House Martins, and Alpine Swifts so low overhead we could hear the wind through those arcuate wings. Careful scanning of the big flocks produced the only Red-rumped Swallow of the tour, one of just a handful I’ve ever seen in southern France and a life bird for several members of our delightful group.

It also pays to watch the rocks in the water, habitual perches for everything from Black Redstarts to Little Egrets.

The blue flash of the Common Kingfisher is a frequent sight here, too, but it is usually little more than that, an electric streak tracing the course of the river below us. This time, though, one decided that the waters directly in front of us must harbor the finest fish in France, and she hovered and dived for minutes at a time in plain view, coming up over and over with tiny silvery snacks. Yes, it’s a common bird, and no, we never miss it, but this may have been my favorite kingfisher experience ever.

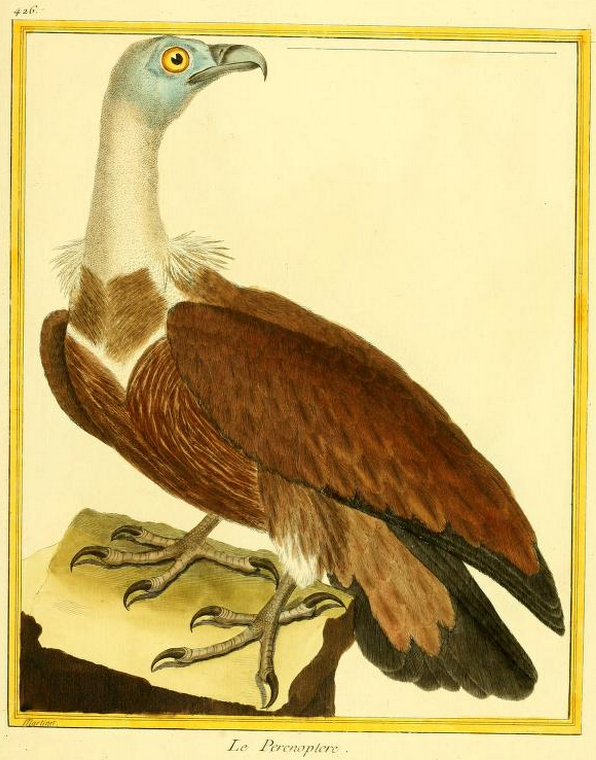

The clock reminded me that we needed to get to lunch in Beaucaire, and so I reluctantly sounded the retreat, Rock Sparrows or no. As we neared the parking lot, a great shadow passed over — and we looked up to find it cast by a Griffon Vulture. The great fulvous bird soared above us for several minutes before passing to the west, leaving us to wonder whether it was a bird from the Alps, the Pyrenees, or the central French massifs driven out into the lowlands of the Gard by hunger or curiosity.

Back when this species could still be spoken of as common, Crespon recounted the “manière particulière” with which the residents of the Cevennes hunted the great vultures:

It is a matter simply of constructing a square enclosure with sticks; they throw a piece of carrion into the middle of it, and in no time the vile odor that it gives off attracts the vultures, which drop out of the sky to feed. But once they have landed inside the enclosure, it is impossible for them to take flight again within the confines of the enclosure (their wings are so long that they need space to jump several times before being able to take off). And so it is easy to take them alive.

Just what the bold hunters wanted with these birds is unclear. Buffon notes that they — the vultures, that is —

are disgusting, thanks to the constant streaming of fluid from their nostrils, along with saliva that pours from two holes in the bill.

Not overly appealing, but it’s a great bird to see.