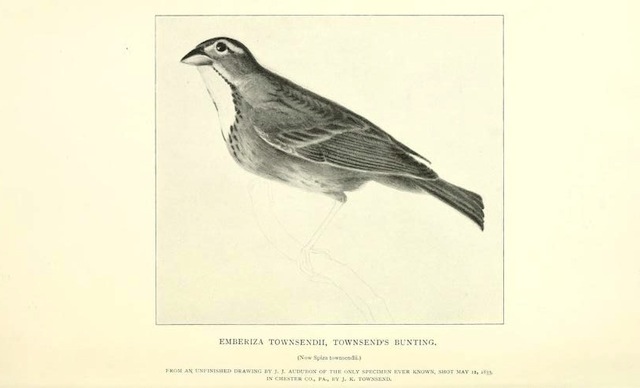

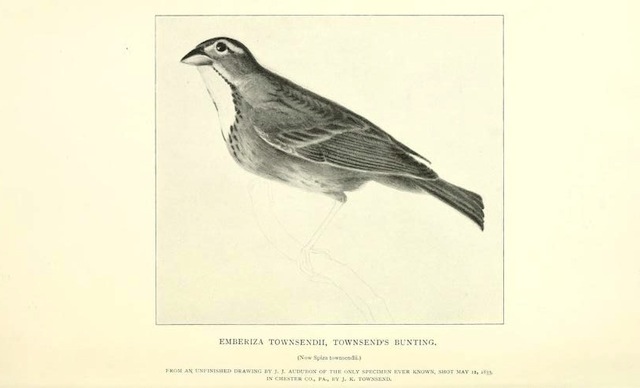

This year’s World Series of Birding will be run under the mysterious shadow of the Townsend’s Bunting, a bird collected for the first time just across the river in Chester County, Pennsylvania, exactly 180 years ago today.

Just what this bird is, or was, has never been clear. Audubon described it from a specimen taken by John K. Townsend for the collection of the botanist, zoologist, and Quaker historian Ezra Michener.

Though the collector furnished some details of the bird’s song and flight attitudes, Audubon himself said that “nothing is known of its habits,” a verdict that is unlikely ever to be reversed: for the shy bird with the loud, lively, and varied song that Townsend shot that May day in Philadelphia was the last of its kind ever encountered.

For a century and a half following its discovery, Townsend’s Bunting, named by Audubon as a “tribute of respect to [Townsend] in honor of his great attainments in ornithology,” was generally believed to represent a distinct taxon, almost surely extinct. While Elliott Coues had suggested as early as 1884 that the puzzling skin might be a hybrid, perhaps between a Dickcissel and a Blue Grosbeak, the first six editions of the AOU Check-list reject that possibility:

its peculiarities cannot be accounted for by hybridism [or] probably [the Fifth and Sixth editions here read “apparently“] by individual variation.

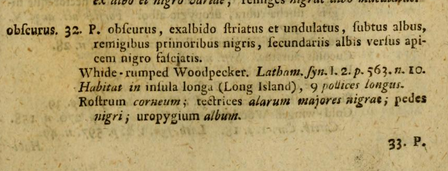

In 1985, Kenneth C. Parkes reached a different conclusion. Townsend himself had been “at first inclined to consider this species as identical with the Black-throated Bunting,” which we now know as the Dickcissel. Parkes’s examination of the specimen, which still resides in the collections of the United States National Museum, led him to propose

that it is a female Spiza americana that lacks the normal carotenoid pigment in its plumage,

a view reported approvingly in the latest edition of the Check-list.

All this is well known. What is invariably omitted from the modern accounts of Townsend’s Bunting, however, is a strange and wonderful statement offered by Coues, first in the second edition of his Check List and then repeated in the second, third, fourth, and fifth editions of the Key. This bird, he writes, is a “standing puzzle to ornithologists,” and “no second specimen of this alleged species is known.” And then:

it is not improbable that the type came from an egg laid by S. americana [the Dickcissel]. But even such immediate ancestry would not forbid recognition of “specific characters”; the solitary bird having been killed, it represents a species which died at its birth.

Natura non facit saltus, indeed; but this seems a leap to me. I think that Coues explains what he means in the General Ornithology prefacing the Key:

no such thing as species, in the old sense of the word, exist in nature…. their nominal recognition is a pure convention…. We treat as “specific” any form, however little different from the next, that we do not know or believe to intergrade with that next one…. the differentiation is accomplished, the links are lost, and the characters actually become “specific.”

What I find so wonderful here is the way in which Coues, convinced Darwinist that he was, is still, like every other natural historian before the Modern Synthesis, tangled up in a purely typological view of difference and relationship. Because the chick that emerged from that egg in 1832 or so was visually, morphologically different from its immediate ancestors — “morphology being the safest, indeed the only safe, clue to natural affinities” — it was distinct at the conventional level of species from the parent that laid that egg. Not a freak, not a variant, not a hybrid, but a new and distinct species deserving of its own name and its own category of thought.

However we understand Townsend’s Bunting, as a bit of spontaneous species creation, a hybrid, a “schizochroistic” variant, you would think that the mechanism behind its production 180 years ago would still be out there, waiting to bring forth another. Maybe today, as hundreds of birders scour the state, New Jersey will get its first record of this “standing puzzle.”

But what would we call it?