This year marks the 300th anniversary of the birth of Jean-Thomas Aubry, one of the great natural history collectors of eighteenth-century France. Both Buffon and Brisson, the two most important ornithological cataloguers of the day, made extensive use of the birds in his cabinet, shipped back to France by correspondents and collectors around the world.

With characteristic graciousness, Buffon thanked the good Abbé:

We have often been furnished with specimens of new animals unknown to us by the Curate of St-Louis, whose beautiful collections are known to all scientists and scholars, and who combines a great knowledge of natural history with an eagerness to make that knowledge useful by freely and generously sharing all that he possesses of this nature.

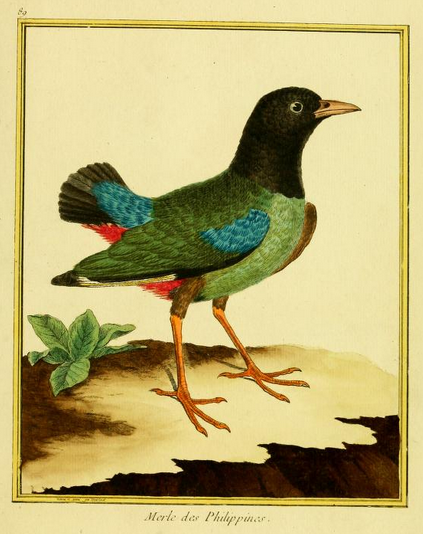

Among the birds first described from Aubry’s collection was what Mathurin Brisson called the “merle verd à tête noire des Moluques,” the Moluccan black-headed thrush or, as we know it today, the hooded pitta.

The engraving cannot do this colorful bird justice, but Brisson’s description helps:

The head, the chin, and the throat are black. The back and the scapulars are deep green. The breast, upper belly, and flanks are of a brighter green. The lower belly is covered with feathers that are black at the base and tipped with pink. The undertail coverts are entirely pink. The rump, uppertail coverts, and wing coverts are a dazzling aquamarine. The primaries are black at the base, then white, and tipped with blackish brown; the secondaries are blackish, with the outer webs fringed with green; the tertials are entirely green. The tail is made up of twelve black feathers.

Buffon, observing “the structural differences by which Nature herself has distinguished them from the thrushes,” recognized the pittas as a distinct group, and eventually renamed Brisson’s bird — still labeled “merle” in the Planches enluminées — the “breve des Philippines.”

While Buffon’s description is, surprisingly, fairly terse, Martinet’s new plate brings all the bird’s astonishing colors to life.

As of the mid-1770s, these two images and descriptions, and the now-lost specimen on which they were based, was all that European science knew about this colorful pitta. That is more than enough, though, to make me wonder what on earth was going through Philipp Ludwig Statius Müller’s mind in 1776 when he — with an explicit citation to Buffon — gave this pitta its “official” Linnaean name.

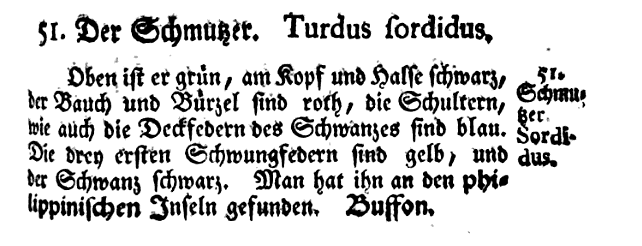

It is green above, black on the head and neck; the belly and rump are red, and the shoulders and tail coverts are blue. The three outermost primaries are yellow, and the tail is black. It is found in the Philippine Islands.

A brief description, obviously based exclusively on Martinet’s plate and simplified to the point of inaccuracy (compare Brisson’s description of the primaries with Müller’s) — but it still makes clear that this is a striking, brightly colored bird.

So what does Müller name it?

Der Schmutzer. Turdus sordidus.

There are plenty of birds named sordidus/a/um or sordidior or sordidulus or sordidatus, and all but this garish pitta live up to it by being more or less dull, dingy, drab.

I can buy sordidulus for the western wood-pewee, but Müller, unless he was completely off his ornithorocker, must have had some reason other than color to name his pitta sordidus (now, of course, it’s Pitta sordida).

That Müller had not committed a typo, or intended an otherwise unattested meaning of the Latin adjective, is clear from his simultaneous coining of the German name “Schmutzer,” something that smudges or stains (or is smudged or stained). What was in the back of his mind? Did he have a poorly colored copy of Buffon? Did the black head make him think the bird fed in the mud? Or did the dark bases of the pinkish belly feathers call to mind some sort of soiling?

Who can figure this out for me?