We forget how strange most birding conversation must sound to the occasional eavesdropper of more normal habits and predilections. Many of the words and the names that trip so easily from our tongues sound strange at best, and silly at worst, in mixed company.

I don’t mean just the obvious ones, the sapsuckers and the flowerpiercers and the boobies, but even names that seem perfectly usual to “us” — but entirely foreign to “them.”

Nuthatch.

Bittern.

Junco.

Especially this time of year, when fields and feeders are aflutter with those sturdy gray sparrows from the north woods, we birders say “junco” all the time without a second thought.

But if we do think twice, it’s a funny name, isn’t it? English words don’t really look like that, and it’s hard to figure out what on earth this one could mean.

Hard, it turns out, not just for the average birdworder like me, but for just about everyone, it seems. Still our great coryphaeus in such matters, Elliott Coues sets a rare question mark next to the etymology from “juncus, a rush,” and Choate sniffs that this is

a singularly inappropriate name for a genus whose habitat is not among the reeds.

Terres is always good for an often good alternative, but here he offers only the speculation that the name in question refers to the color of reeds. I’m not buying it.

Not even Johann Georg Wagler, naming this genus in the Isis in 1831, provides a clue as to why he should have chosen the name Junco for the new “Finkammer,” and his promise of a more detailed investigation to come was left unfulfilled when he died, at the age of 32, a year later.

But the name “junco” was not new in 1831. It had in fact already been applied, in Latin and the vernacular, to birds of the Old World well before Wagler appropriated it for his new genus of Mexican sparrows.

If we go back nearly three centuries before Wagler, we find that the sixteenth-century Saxon poet and antiquarian Georg Fabricius knew “Junco” as a name for one of the wagtails.

In 1789, Cornelius Nozeman and Maarten Houttuyn used “junco” as a scientific name — but as a species epithet, not a genus designation. In their Nederlandsche vogelen, those authors named the bird we now know as the Eurasian Reed Warbler Turdus junco, “reed thrush.”

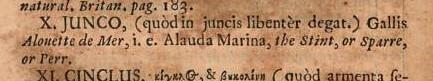

In 1668, Charleton included two entries for the junco in his Onomasticon.

This bird, he so reasonably says, is called the “junco” because it “readily passes its time among the reeds.” The French call it the “sea lark,” the English a “stint.” This junco seems to have been a shorebird.

And, at the same time, a bunting.

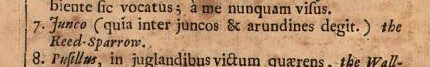

That second usage goes back at least to William Turner, who, working from Theodorus Gaza‘s translations of Aristotle, determined that this was what The Philosopher must have meant with his “junco”:

Since I do not know any small bird living in the rushes and reeds other than the one called by the English “rede sparrow,” I believe that that must be the “junco.” It is a small bird, a little smaller than the House Sparrow, with a rather long tail and a black head. The rest is dusky.

Turner’s identification was sufficiently cogent as to be taken over (probably by way of Charleton) into Phillips’s New World of English Words, which — a good century and a quarter before Wagler — defines “junco” as precisely that same “Reed-Sparrow, a Bird” we now call the Reed Bunting. Phillips’s definition, quoted in the OED as well, probably provides the evidence backing James Jobling’s concise entry in the Helm Dictionary: “Junco Med.L. junco Reed Bunting (>L. juncus reed).”

How, though, did the name shift from an emberizid out in those vast Old World beds of juncaceous vegetation to our demure gray sparrow of open woodlands and winter suburbs?

There is a clue, I think, in one of the alternative names of the Reed Bunting. Swann tells us that this species is also known, misleadingly enough, as the “Black-headed Bunting,”

frequently so called provincially on account of its black head.

For Turner, too, the black head was this bird’s distinctive plumage character — indeed, the only plumage character he mentions at all.

My theory is that Wagler, confronted for the first time with the skin of an unknown dusky-plumed bunting-like bird with a black head, recalled that familiar European bunting. Wagler did not know the habitat preferences of his new bird, and was not thinking of reeds and rushes when he named it. What he did know was that in its most conspicuous plumage mark, the dark-hooded head, it resembled the Reed Bunting — and most importantly, he knew that the slightly odd word “junco” was available for scientific use.

And today, nearly 200 years later, available for the rest of us, too, when we look at the window and wonder what those little gray birds at the feeder could possibly be called.