Nathan writes:

Audubon cites the Great Crested Grebe as being “not uncommon during autumn and early spring on all the larger streams of the Western Country….” Does anyone know anything about this?

Well, no, not really — not beyond the general observation that even Homer naps. And this time, the dozing was a doozy.

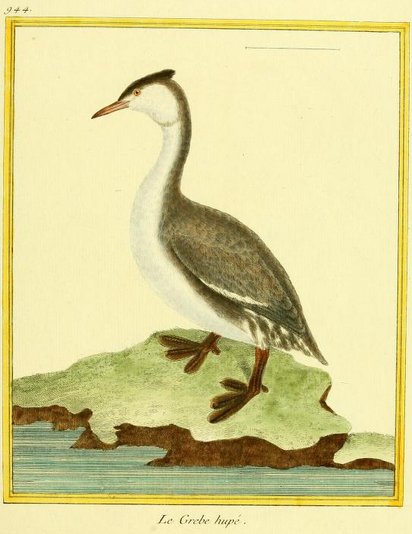

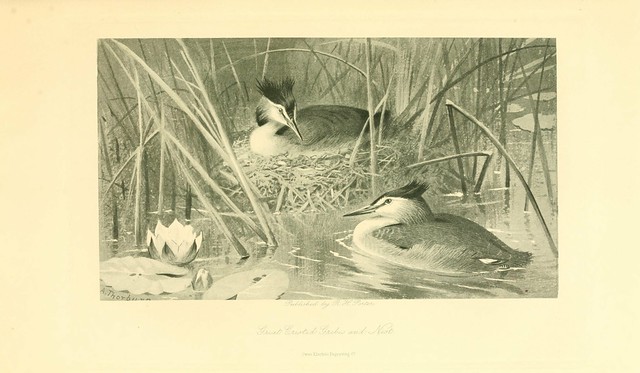

This handsome plate, number 292 of the 435 that would eventually make up the Birds of America, was engraved in 1835 from a painting about which I know nothing else. It seems likely that Audubon drew the birds during one of his sojourns in England, but we cannot be certain that this plate is not based on specimens he borrowed from one or another American collector.

The passage Nathan mentions is from the Synopsis of the Birds of North America, a much-needed taxonomic concordance to the plates and the Ornithological Biography, published in Edinburgh and London in 1839. Audubon provides a full description of the bird in the Synopsis, but has virtually nothing to say there about its habits in its putative North American range:

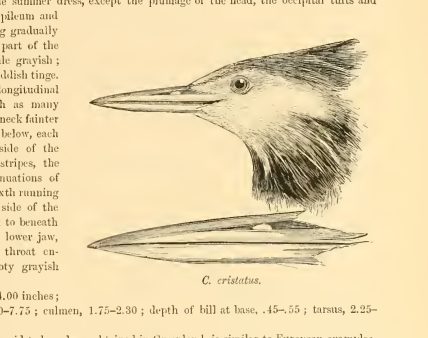

In contrast, the complete account in the Ornithological Biography, which appeared in 1835, is lavish in its detail. The technical descriptions, prepared with (or quite possibly by) MacGillivray, are as complete as any offered for any species, and include the measurements of eggs lent to Audubon by William Yarrell.

What startles is not that Audubon should have accounted this exclusively Old World bird an American species — an easy enough mistake in the days when specimens and their labels did not invariably keep the closest of company — but how, in the Ornithological Biography, he compounds his error with what we can read only as a series of scandalously precise fictions. On his own authority, Audubon tells us that “this beautiful species”

returns from its northern places of residence, and passes over the Western Country, about the beginning of September…. I have observed them thus passing in Autumn, for several years in succession, over different parts of the Ohio, at all hours of the day. On such occasions I could readily distinguish the old from the young, the former being in many instances still adorned with their summer head-dress…. on the Ohio’s rising I have observed that they abandon the river and betake themselves to the clear ponds of the interior…. When these birds leave the southern waters about the beginning of April, the old already shew their summer head-dress….

Audubon’s words paint the vivid picture of regular visible migration over the Ohio Valley, “in flocks of seven or eight to fifty or more” — by a species never before and never since reliably reported on the continent. To forestall any suspicion that he was mistaking this species for what was then the only other large podicipedid known from North America, Audubon assures his reader that the Great Crested and the Red-necked Grebes prefer different habitats.

All very odd indeed. But Audubon, it turns out, was not alone in assuming that this large Palearctic grebe also occurred in the New World.

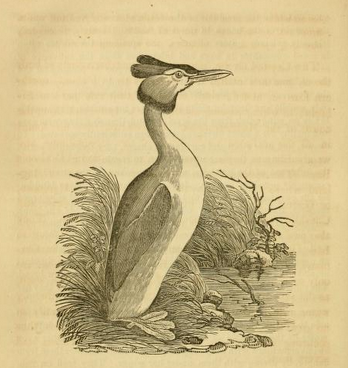

The Great Crested Grebe received its formal binomial from Linnaeus himself, in the authoritative Tenth Edition of the Systema. But the bird, widespread and conspicuous in western Europe, had been known to science for hundreds of years. The descriptions of most of the diving birds given by the ancients can hardly be untangled today, but Severus Sulpicius, the fourth-century historian, is said by Conrad Gesner to have described a grebe with “red feathers like horns on its head.”

Gesner himself, writing in the 1550s, does his best to work out the identity of the larger divers. He appears first to describe the Red-necked Grebe, “known to the Venetians as the sperga,” before turning to a different “genus” found in Switzerland,

quite similar to the others, but crested with plumes sticking up around its crown and upper neck, black at the top and reddish towards the sides, like the hair of a fox.

Not a bad description of a Great Crested Grebe — or of Gesner’s illustration of the species. The Swiss naturalist, like his contemporary Belon, also points out that this, and all grebes, “has its feet at its tail,” an observation behind a great many names for these birds, including the latinizing podiceps, the Dutch arsevoet, and the Savoyard loere, which, Gesner, tells us, is also used as a pejorative for

a fat and lazy person, because of the well-known reluctance of this bird to walk on land.

At the end of the sixteenth century, Aldrovandi copies Gesner’s text into his Ornithologiae — but for some inscrutable reason replaces the perfectly serviceable woodcut there with his own, slightly less successful image of a Great Crested Grebe (Brisson, in a major lapse of taste, calls it “satis accurata”).

We’re on firmer artistic ground with Francis Willughby’s “Crested Diver, or Loon,” a friendly-looking bird with perfectly creditable feet and bill.

Willughby and Ray are at pains to distinguish this bird –which they identify with the one described by Aldrovandi and Gesner — from another, “something less” in size, apparently our Eared / Black-necked Grebe. Unfortunately, the English names they assign each only add to the already enormous potential for confusion. The first they call “The greater crested or copped Doucker,” the second “The greater crested and horned Doucker.” It’s little wonder that even 150 years later Audubon could be confused.

All of these authors agreed on one thing: whatever the bird they were describing and depicting was, its range was Europe. George Edwards was able to cite specimens from Switzerland and England; the Dutch translator of Seligmann’s Recueil even named the bird “de groote Geneefsche Duiker,” the Great Grebe of Lake Geneva.

John Latham, who coined the genus name Podiceps, put it simply and definitively:

Habitat in Europa boreali,

collapsing slightly the detail given five years earlier by Thomas Pennant in the Arctic Zoology, who had added “every reedy lake” in Iceland and Siberia to the species’ known range.

The first forthright assertion I know of of the Great Crested Grebe as an American bird actually antedates Pennant and Latham. In 1781, Buffon and his busy workshop of collaborators published the eighth volume of the Histoire naturelle des oiseaux, comprising accounts of — among many others — the grebes.

A comparison of the information provided by ornithologists shows that the Great Crested Grebe is found both on the sea and on lakes, in the Mediterranean and on our ocean shores: its species is even found in North America, and we have identified it as the acitli from the Gulf of Mexico of Hernandez.

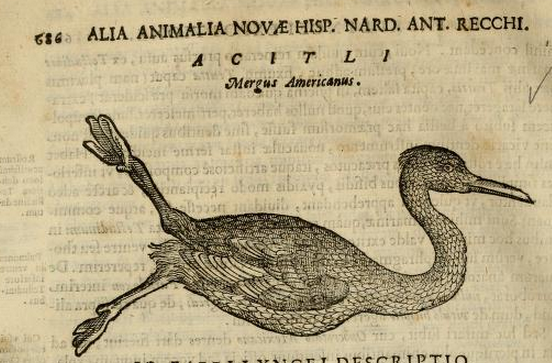

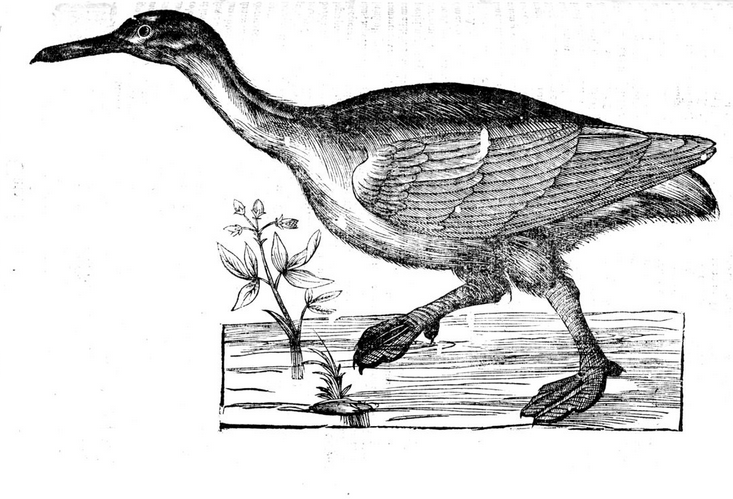

It is not clear, of course, just what the so steadfastly anti-Linnaean Frenchman means when he speaks of “son espèce,” but Buffon appears to have arrived at the suspicion put forward by Willughby and Ray in their account of the “Water-Hare, or crested Mexican Doucker” described in Hernandez’s Thesaurus.

Between this and the precedent [species, namely, the Great Crested Grebe] there is so little difference, that I scarce doubt but they are the same.

And we can scarce doubt that the Thesaurus does, in fact illustrate a bird with feet set far back on the body and terminating in extravagantly lobed toes. Johannes Faber, the papal physician who provided Hernandez with the description of this bird, was himself not entirely sure what to make of it, as his extremely long, extremely learned, and extremely tiresome discussion shows. He finally concludes that the bird must be “the American Mergus,” a name that in fact tells us nothing, given its vast range of application over the centuries to essentially any bird that spends time in the water and dives. There is no positive indication in Faber’s dissertation that he considers this Mexican diver identical with the Great Crested Grebe of Europe (I suspect that the picture is a semi-fanciful rendering of a Sungrebe); but his use of the vague label “mergus,” coupled with the grebishness of the illustration, made it possible for Ray and Buffon — perhaps independently of each other — to take the next step.

And with that, I think, the feathered die was cast. Temminck continued to treat the species as entirely European, but Charles Lucian Bonaparte followed Buffon in his 1827 Synopsis, affirming that the Great Crested Grebe

inhabits the north of both continents: rare in the middle states, and only during winter: common in the interior and on the lakes.

John Richardson, in the Fauna boreali-americana, even goes so far in 1831 as to describe a specimen that he says was “killed on the Saskatchewan,” surely — surely — a misidentified Red-necked Grebe.

The extensive account of the Crested Grebe, or “Gaunt,” in Thomas Nuttall’s Manual probably led Audubon more strongly down the path of error than any other source.

Nuttall’s text relies especially closely on Pennant, carefully including Siberia in the species’ Old World range and even borrowing the pretty phrase “reedy lakes” to describes its breeding habitat. His most fateful borrowings, though, are from Richardson, and it is here, in some incautious copying, that we find the immediate inspiration for Audubon’s later misapprehensions.

The Fauna boreali-americana correctly and sensibly informs us that

the Grebes are to be found in all the secluded lakes of the mountainous and woody districts of the fur countries, swimming and diving….

Unfortunately, Richardson and Swainson’s printer set that paragraph, intended as an introduction to the general status of all grebes in the northern reaches of North America, beneath rather than before the header for the species Podiceps cristatus, the Great Crested Grebe, making it seem to the careless reader that the statement applies to that species alone.

Nuttall’s research assistant was, apparently, one of those careless readers, and this was the result in the Manual:

The Crested Grebe, inhabiting the northern parts of both the old and new continents … [is] found in all the secluded reedy lakes of the mountainous and woody districts, in the remote fur countries around Hudson’s Bay,

a neat compilation of Pennant and Richardson — but not true at all.

Audubon did not notice the error — he probably didn’t consult Richardson directly at all — and Nuttall’s statement seems to have been all it took to set Audubon to spinning the wild tale he tells in the Ornithological Biography.

And it took considerable time before that tale was refuted. George Lawrence, in the ornithological report of the Pacific Railroad Surveys, reports no fewer than five specimens of the Great Crested Grebe from North America, two from Shoalwater Bay, in present-day Washington, and three from the “Atlantic coast.” Spencer Baird owned one of those latter skins, said to have been collected by Audubon himself; it’s no surprise, then, that Baird included the species on the list of the birds of North America he published in 1859.

Elliott Coues, too, listed cristatus among the birds credited to “Amer.Sept.” when he presented an overview of the continent’s grebes in 1862, and he retained the species in the first edition of the Key and in the 1873 Check List; the greatly expanded and fully reworked second edition of the list would call the grebe “extra-limital, as far as known.”

Meanwhile, the Great Crested Grebe had been determined to be “occasionally observed about the submerged meadows on Long Island,” and recorded from “New York, Long and Staten Islands, and the adjacent parts of New Jersey.” It was said to breed “about fresh water late in the season” in Maine (though “not common”), and was “not uncommon” in winter in eastern Pennsylvania and New Jersey.

Not until 1881, nearly half a century after the publication of Audubon’s effusions, did a young Robert Ridgway suggest, tentatively, the removal of the species from the North American list. In the appendix to his Nomenclature, Ridgway annotated the name Podiceps cristatus, Lath., with a simple question:

Not North American?

Three years later, Baird and Ridgway provided a definitive answer to that query.

In the Water Birds of 1884, they give the range of the Great Crested Grebe as the “Northern part of the Palaearctic Region; also, New Zealand and Australia. No valid North American record!” The italics and the startling exclamation point are the authors’, and they go on to call

the occurrence of C. cristatus — which for half a century or more has been included in most works on North American ornithology, and generally considered a common bird of this country — …so very doubtful that there is not a single reliable record of its having been taken on this continent.

As late as 1894, a full decade later, Coues was still warning his readers that the grebe might “have been hastily eliminated from our fauna,” but the final edition of the Key finally admits that the species is “not authentic” on the list of North American birds.

The American Ornithologists’ Union, graced by late birth, never really had to face the question. The Great Crested Grebe is included in none of the editions of its Check-List, and as far as I know, the nearest this species has been authentically — to use the Couesian term — recorded to North America is Gran Canaria, where a single adult appeared in December 1984.

Not to rule out the possibility, of course. Birds have wings and they fly, as someone long ago pointed out.

But it’s unlikely, at least on the scale of human history, that we will ever see Audubonian flocks of this lovely species flying south through the center of the North American continent. That was a possibility — an imaginary possibility — only thanks to some sloppy printing, some careless reading, and the unbounded fantasy of the greatest American ornithologist of his time.