Not the warbler. The owl. Yes, Kirtland’s Owl.

It’s obvious enough to us now what this once-mysterious bird was — is — but two and a quarter centuries ago, when even the diurnal birds of North America were still imperfectly known, these tiny chocolate owls were a real puzzle to the first European naturalists who stumbled across them in the dim wildnesses of northern North America.

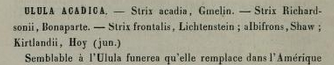

George Shaw, renowned as the cataloguer of the Leverian Museum, was the first to describe this little predator, naming it, in his Naturalists’ Miscellany of 1794, Strix albifrons, the White-fronted Owl:

I don’t believe that this extremely small species of owl has ever been depicted or described before. It breeds in North America, especially in Canada. The female is thought to lack the white forehead that distinguishes the male. The White-fronted Owl belongs to that group in the genus which contains the birds called “smooth-headed” or “earless.”

Seven years later, John Latham provided a much more detailed description, along with a little information about the origin of his specimens,

brought from Quebec, by General Davies, in 1790.

Thomas Davies had commanded the British artillery in Quebec. On his return to England, he contributed to Latham’s studies not just a number of American specimens, but also several of his own extremely skillful watercolors of birds — not, unfortunately, including the owl.

Davies told Latham that in life

this bird frequently erected two feathers over the eye,

a detail that may have inspired the first doubts about this owl’s status as a distinct species. In 1807, Louis Jean Pierre Vieillot placed the Hibou à front blanc among the “eared” owls, even though

its tufts are composed of only two or three feathers above the eyes and no longer than any of the others.

After quoting Latham at length, Vieillot poses a good question:

Given their similarity to the Long-eared Owl, might these birds not instead be young birds of that species, which inhabits the same region?

The first really serious attempt to sort out the identity of this tiny owl was made by Lichtenstein in his June 1837 investigation of the birds of the American west coast, based on specimens sent to Berlin by Ferdinand Deppe.

This bird is distinguished from all other small North American owls by its short tail and the distinct spotting on the remiges. Those characteristics make it impossible to confuse it with the smallest of our northern European owl (the true Strix passerina of Linnaeus), which seems nevertheless, in spite of the significant size difference, to hae happened so often…. Strix passerina (Linn.) is, I am entirely convinced, not found in America, and Latham’s Strix acadica, with which it has so often been combined, is, to judge by Latham’s description and by his illustration, in fact nothing more than the immature plumage of our Strix frontalis.

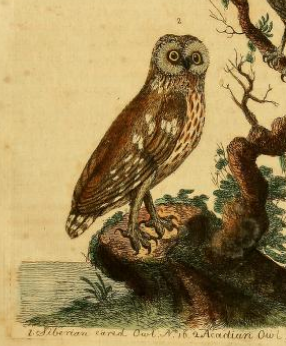

Latham received his Acadian Owl from General Davies, who had painted the species in Nova Scotia — no doubt with much greater skill than Latham himself, whose own Northern Saw-whet Owl isn’t terribly convincing.

Lichtenstein goes on to correct Wilson and Nuttall, both of whom he says, failed to recognize the distinctness of the Old World’s Pygmy Owl from Latham’s Acadian Owl, resulting in the false application of Linnaeus’s name passerina to the bird of the New World.

Lichtenstein, satisfied that he had solved the mystery with his identification of Latham’s acadica as simply the immature form of albifrons, proceeded to offer an intriguing theory:

Latham received his specimen of the Acadian Owl, as its name suggests, from Nova Scotia, and Nuttall says that it is found south to New Jersey. We are also in possession of several specimens in immature plumage from such eastern regions, but we have received adult birds only from California. Thus, the west seems to be this bird’s actual home, where it breeds, while only young birds fly beyond those boundaries, just as other birds exhibit a similar pattern in Europe.

All quite logical. All quite wrong.

It’s a good measure of how hard it was in the mid-nineteenth century to keep abreast of the ornithological literature — especially that published on another continent — that in 1852, fully fifteen years after Lichtenstein’s would-be solution to the whole problem, Philo Romayne Hoy could describe Shaw’s owl again, half a century after its first publication. Hoy writes

But two specimens of this bird have been taken to my knowledge; the first was captured Oct., 1821, and kept until winter when it made its escape; the second, and the one from which [Hoy’s] description was taken, flew into an open shop, July, 1852…. It is different from any other species yet known to inhabit North America, and appears to have some general resemblance in color to N. Harrisii, Cassin, but not sufficient to render it necessary to state their difference.

Hoy named his “new” species Nyctale Kirtlandii,

as a slight tribute of respect to that zealous Naturalist, Prof. Jared P. Kirtland, of Cleveland, Ohio,

the same man to whom Spencer Baird, in that same year, dedicated the warbler.

Baird and Cassin, in the 1858 report of the Pacific Railroad Expeditions, filled in the bibliographic blanks, and explicitly rejected Lichtenstein’s interpretation of the slender specimen record:

It is given by Professor Lichtenstein … as identical with N. acadica…. This bird is about the size of Nyctale acadica, but is quite distinct, and in fact, bears but little resemblance to that species. We have no doubt that it is the true Strix albifrons, Shaw,

a species, they say, “lost sight of by naturalists for upwards of half a century, and until brought to light by the researches of Dr. Hoy.”

In the years following that so confident assertion, American ornithologists tended to recognize the Kirtland’s Owl as distinct, while Europeans were more likely to follow Lichtenstein in considering the bird the adult of the Northern Saw-whet Owl. Hermann Schlegel, for example, synonymized the two in his 1862 catalogue of the birds of the Leiden museum:

Baird, on the other hand, still maintained the specific status of albifrons in his 1870 edition of Cooper’s California Ornithology:

The very next year, however, Baird wrote to A.E. Verrill — Yale’s first professor of zoology — with his suspicion that albifrons might after all just be the young of the Northern Saw-whet Owl. Verrill wasn’t entirely convinced:

if so, it is singular that the young of the latter has not oftener been observed in localities where it is common, as in many parts of New England. This question is well worthy of thorough investigation.

And that’s just what it got, finally. The spark seems to have been provided by Daniel Giraud Elliot, who in 1872 published an article in the Ibis in which he definitively identified the owl of Shaw and Hoy as “the young of the true N. tengmalmi,” a determination reached on Elliot’s examining five specimens of that bird.

The response was prompt and vigorous. Robert Ridgway immediately took issue with Elliot’s “erroneous” opinion. The so-called American White-fronted Owl, he writes,

is scarcely more than half the size of the N. Tengmalmi, and cannot, by any means, be referred to the latter species.

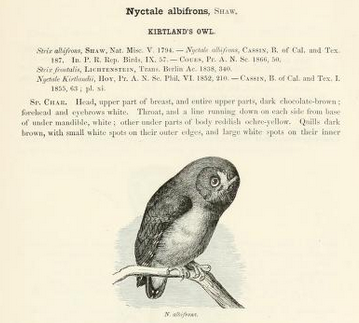

Instead, Ridgway argues, there is a “direct analogy” to be drawn between the differences in the adult and immature plumages of the Boreal Owl and the differences between the White-fronted and the Northern Saw-whet Owls, such that he was satisfied that the latter two should be considered the “old and young of one species.” The specimens held in the collections of the Smithsonian Institution supported Ridgway’s conclusion: the texture of the plumage of all the specimens of albifrons / kirtlandii revealed them all to be “unmistakably” young birds, while all those of acadica were adults. Most tellingly, two of the specimens identified as albifrons / kirtlandii

have new feathers appearing upon the sides of the breast (beneath the brown patch), as well as upon the face; these new feathers are, in the most minute respects, like common (adult) dress of N. Acadica.

Given how notoriously easy these small owls are to capture and to keep, it should have been easy to resolve the issue years earlier with a simple experiment on live birds. The Canadian historian and naturalist James MacPherson Le Moine kept a live Kirtland’s Owl in the early 1860s, apparently for some time, but in the 1864 English translation of his Ornithologie, the bird is still listed as a species distinct from the Northern Saw-whet, even though Le Moine must have seen his strigid pet molt.

In November 1872, having read Ridgway’s American Naturalist article, J.W. Velie of the Chicago Academy of Sciences reported that he had

kept a fine specimen of “Nyctale albifrons” until it moulted and became a fine specimen of Nyctale acadica.

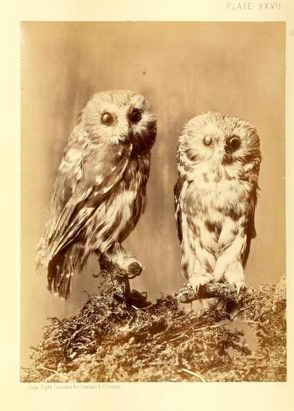

That should have settled things. Coues affirmed Ridgway’s identification in the first edition of the Key: “these are the young,” he writes of albifrons, of the Saw-whet Owl. The 1874 History of North American Birds by Baird, Brewer, and Ridgway naturally simply reproduced the results of Ridgway’s investigations from two years before — and relabeled the drawing from Cooper’s Ornithology and placed it pointedly next to an adult Northern Saw-whet Owl.

With the true state of affairs now endorsed in the era’s two most important handbooks, the story of Kirtland’s Owl should have come to an end. And yet there were holdouts.

In 1876, Henry George Vennor acknowledged that most authorities thought the Kirtland’s to be merely the immature plumage of the Northern Saw-whet Owl — two rather frighteningly mounted specimens of which illustrated his volume Our Birds of Prey — but Vennor could “yet to come no satisfactory conclusion” himself about the identity of the “tawny” birds.

If this tawny form is in truth the young of the Acadian or Saw-whet Owl, it is another of those puzzling instances in which, while the mature birds are plentiful, the young and immature are but rarely met with…. the small proportion of tawny to the ordinary found plumage … may be given as but one in a thousand. Are we, then, really to believe that, while we have such numerous occurrences of typical Acadian Owls, or in other words, of undoubtedly mature birds, we have only occasional accidental occurrence of the young and immature form?

Maybe, Vennor hesitantly suggest, the Kirtland’s Owl is instead a melanistic variant, that pops up with great infrequency, entirely independent of age and sex.

The last serious mention of the Kirtland’s Owl I am aware of appeared 95 years ago in Bert Bailey’s Raptorial Birds of Iowa.

Bailey’s account of the Northern Saw-whet Owl notes, correctly, that “immature birds lack the streaks and spots of the adult,” suggesting that he was aware of the chocolate plumage of the young. And yet, in comparing his list with the 1870 catalogue of Iowa’s avifauna prepared by J.A. Allen, Bailey observes that some species of birds of prey listed by Allen

have not appeared [since], nor have they been authenticated by collected specimens. Among these are Richardson’s Owl and Kirtland’s Owl.

Hope springs, I guess, eternal.

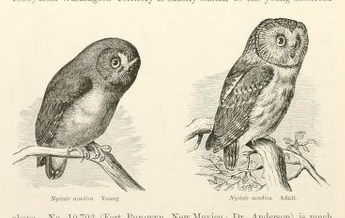

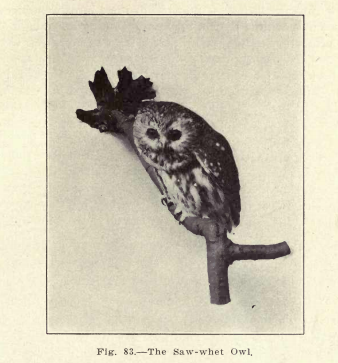

Northern Saw-whet Owl. Or perhaps, just perhaps, an adult Kirtland’s Owl.