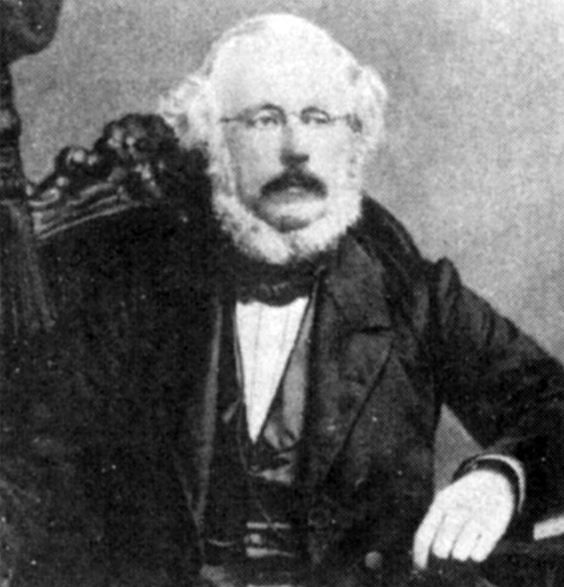

Today marks the 150th anniversary of the death of Edward Harris.

Harris was a wealthy gentleman-farmer from New Jersey, and it was his moral and financial support that in significant part enabled John James Audubon to publish the Birds of America. But Harris was more than just a generous patron and influential advocate; he accompanied Audubon on the long expeditions to Texas and the Gulf in 1837 and up the Missouri River six years later, and the two became to all appearances friends, the title by which Audubon continually refers to him in the Ornithological Biography.

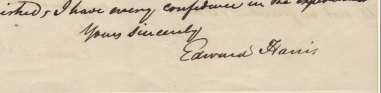

Audubon seems to have trusted Harris implicitly as a natural historian; in dedicating the Harris’s Hawk to his friend, he writes that Harris,

independently of the aid which he has on many occasions afforded me, in prosecuting my examination of our birds, merits this compliment as an enthusiastic Ornithologist.

That may sound like nothing more than a polite floscule, but Audubon repeatedly cites Harris as a reliable authority on the birds of the mid-Atlantic region.

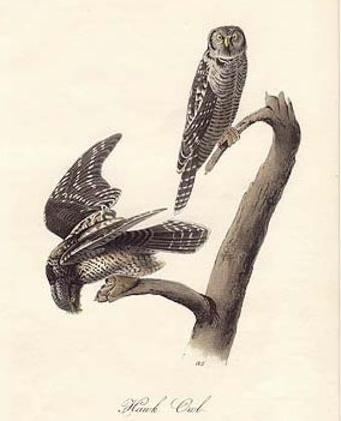

Harris, for example, is Audubon’s source for the red plumage of some female Summer Tanagers, and it is in part on his authority that Audubon pronounces the Henslow’s Sparrow “abundant” in New Jersey (those were the days). Harris’s reports extended the known range of the Carolina Chickadee into New Jersey, and he taught Audubon everything he knew about the Cape May Warbler, a bird the great ornithologist himself never encountered. Harris is even credited with a New Jersey record of the Northern Hawk Owl, a report passed over in discreet silence by the most recent surveys of the state’s birds.

Audubon honored these and Harris’s other contributions by naming not just the hawk but the Harris’s Sparrow for his friend (never mind, of course, that that fine bird had already been discovered, described, and named at least twice by the time Audubon and his party reached the Missouri River).

Harris is also commemorated in the name of a picid.

The first specimens of the Harris’s Woodpecker, now classified as a subspecies of the Hairy Woodpecker, were collected by Townsend on the Columbia River in the mid-1830s; when Audubon came to describe “this singularly marked species,” he

honoured the present Woodpecker with the name of [his] friend Edward Harris, Esq., … for his efficient aid when … [Audubon] was reduced to the lowest degree of indigence…. he merits this tribute as an ardent and successful cultivator of ornithology, and an admirer of the works of Him whose good providence gave [Audubon] so noble-hearted a friend.

At some point, Harris presented Audubon with the skin of a squirrel, also acquired from Townsend; in their Viviparous Quadrupeds, Audubon and John Bachman named the “pretty little” animal Harris’s Marmot Squirrel, now known to every inhabitant of Sonoran Desert suburbs, and loved by most, as the Harris’s Antelope Squirrel.

Nowadays we tend to think of Harris only in his relation to Audubon and the other participants in the Missouri River journey, but as a member of the Academy of Natural Sciences from 1835 on, he had connections to all of Philadelphia’s natural historians of the time. In August 1845, he and the great John Cassin traveled to Cape May, and it was Harris who introduced Cassin and Audubon (an occasion called by George Spencer Morris “a not entirely happy one“). Harris was even Chairman of the Academy’s Ornithological Committee for a time (and not just a member, as Morris would have it); his service in that capacity was commemorated by Cassin in 1849, when he named a “singular and beautiful little” new owl Nyctale Harrissii. In one of those singular and beautiful little symmetries that history is so given to, Cassin had obtained the specimen of what we now know as the Buff-fronted Owl from John Bell, who had been with Audubon, Harris, and the others as a collector and preparator on the Missouri.

Harris’s death was announced to the Academy by Cassin on June 9, the day after the “distinguished naturalist” died at home in Moorestown. The Proceedings had remarkably little to say, describing Harris only as “aged 64, late a member”; one wonders what had happened, whether there was a falling out or whether Harris in his last years, when Lucy Audubon referred to him as “an invalid,” had withdrawn from active participation in events across the river.

In any event, the contemporary reticence on Harris’s death would echo, so to speak, down through the next century and a half. He is remembered, though, in Moorestown, where the drawers that once held his collection of bird skins is now a cherished relic — and a new park is under construction to honor Harris’s interest in exotic draft horses. Maybe today we birders will think of him too.