I didn’t know Roger Peterson, and the closest I can recall having come to meeting The Great Man was a damp morning in Princeton, when there were so many reporters and television cameras in the Institute Woods that we turned around in a righteous huff and went elsewhere.

Or rather: Of course I know Roger Tory Peterson. I’ve known him since my first birdbook (the 1961 Western, a longitudinal misunderstanding on my part ), and I’ve got to know him better and better over the years, obsessively obsessing over the field guides, the prose books, the interviews, the prefaces and forewords, the never-ending flow of words from a man I never met. Over the decades I’ve deduced–or perhaps I’ve constructed–a lifesize picture of Peterson and his life; I’m good at such things, by temperament and by training, and I’m sure that broad swaths of that portrait are as accurate as they are plausible. And I’m sure that even broader swaths are neither.

I remember the eagerness with which I seized on the Devlin and Naismith “biography,” and I remember the disgust with which I put it down: even at 13 I smelled that mouldering whiff of hagiography (remember the scurrilous story of the bloodied dustjacket?). Not the television interviews, not the coffee-table albums of paintings and photos, not the increasingly repetitious essays and forewords gave me what I really wanted–a check on the fantasy vita I’d created, a little historical truth against which to measure years of surmise and suspicion.

As the Peterson centennial approached, two new experiments in biography appeared: the one a “lite” collection of anecdotes, the other a well-researched and solidly written piece of historiography. To my surprise, I’ve enjoyed both, and each has forced me to adjust certain components of my image of Peterson, generally in favor of the man; but both together have rather confirmed a long-held suspicion: that Peterson reached his estimable peak early, and that apart from the wonder that was the 1947 Field Guide, there was a great deal of frustration in Peterson’s efforts.

I don’t remember now just why I was so ready to dislike Elizabeth Rosenthal’s Birdwatcher, but only when Susan Drennan told me that she had been involved in the refereeing of the manuscript did I find myself moved to pick the book up. And I’m glad I did; it’s a delightful read, a gracefully written compilation of stories and anecdotes largely unburdened by argument. Rosenthal relies heavily on long quotes from interviews conducted with Peterson’s family, friends, and acolytes; for the most part, these are neatly integrated into her larger text, with only the occasional editorial officiousness (my favorite: “stable chemicals” is emended to “stable [of] chemicals”!).

I don’t mean at all to suggest that the book is aimless or unstructured. It begins with Peterson’s birth and ends with his death; in between we learn about his fortes and his flaws, his childish relationships with women and his profound friendship with his polar opposite, James Fisher. We encounter a hopelessly abstracted and slightly creepy Peterson–voiding his bladder in public, “rating” strange women on train platforms–and a gloomy, moody Peterson whose fear of age and death took him to the plastic surgeon more than once. More fascinating, perhaps, are the portraits Rosenthal sketches of many of Peterson’s associates, friends, and partners, their names familiar to birders from decades of printed acknowledgments but their lives and personalities until now pretty much lost. The three wives in particular gain dimension in Rosenthal’s accounts; Barbara Peterson turns out–as any careful reader of Wild America must have guessed–to be strong and engaging and intelligent (not to mention long-suffering), to my mind at least as rewarding a subject for biography as her famous husband. Virginia Peterson, on the other hand, comes off as the Lady Macbeth she’d long been rumored to be; at times her depiction descends almost to caricature, and I find myself wondering whether the picture painted here is entirely fair–especially given the occasional positive comment about her from the lips and pens of Peterson’s later acolytes. The first wife, Mildred Peterson, remains a relative mystery. Rosenthal is able to provide some details about her family and background–distinguished and privileged, respectively–but this great-great…niece of George Washington disappears from the biography as surely as she seems to have disappeared from her ex-husband’s life, surfacing only briefly on her accidental death many years later.

To the extent that Birdwatcher presents an argument, it is found in the central 100 pages of the book, where Rosenthal treats Peterson’s conservation activities in, especially, the 1960s, identifying him as among the prima mobilia of a burgeoning world-wide environmental movement. Peterson’s own early work, conducted for the US Army in the 1940s, on the effects of pesticides was incidental and inconclusive, but he was an early and influential supporter of Rachel Carlson in her search for a publisher for Silent Spring; the Petersons also provided support and assistance to researchers seeking the causes of the decline of the Osprey in coastal Connecticut. Peterson’s visit with Guy Mountfort to the wild Doñana raised worldwide awareness of the threats to one of Europe’s most important landscapes, ultimately resulting in its preservation.

These are great accomplishments, but Rosenthal’s accounts of Peterson’s role in them are somewhat undermined by comments she reproduces from others involved: the recurring remarks that Peterson was always willing to lend his name to a worthy cause begin to sound rather like back-handed compliments. I have no reason at all to doubt Rosenthal in this matter, but especially given those comments, I would like to have seen in the supporting documentation for this section more citations to primary archival materials than to popular articles from Peterson’s own pen. My suspicion remains that Peterson’s active and direct contributions to conservation may be a little overstated here, even as his influence–the influence of his field guides–even now on many of the leaders of the environmental movement can hardly be exaggerated.

The field guides, both those Peterson created and those he edited, weighed heavily on him in the last decades of his life. Rosenthal’s final chapters recount an unending conflict between what he considered the responsibility to update the guides and the desire to indulge himself in photography and travel. For the reader, those stories are made the more melancholy by our knowledge–shared, and forcefully expressed, by some of Peterson’s friends as early as 1980–that however strenuous his efforts, the bird guides had been rendered largely obsolete, and that from many birders’ perspectives, Peterson was honoring an imaginary obligation in devoting so much of his time to them. Saddest of all is the notion, given voice repeatedly in the last three decades of Peterson’s life, that the field guide work was keeping him from pursuing his studio painting, a complaint Rosenthal reports without comment or irony.

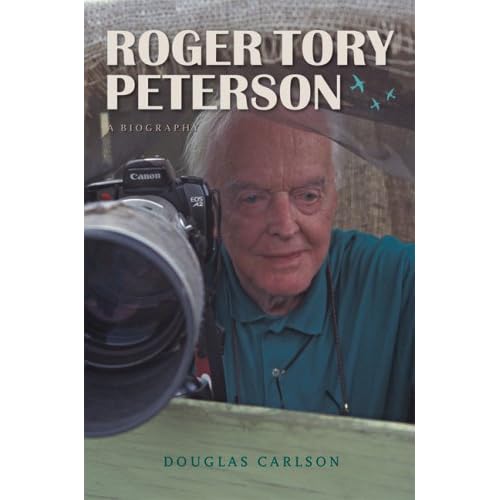

The tension the older Peterson experienced between his art, his field guides, and his indulgences is at the center of Doug Carlson’s fine Roger Tory Peterson: A Biography. Folk wisdom to the contrary, you can tell a book by its cover, and where Rosenthal’s shows the young Peterson at the top of his game, confidently and slightly ridiculously assuming the pose of Goethe in the Campagna, Carlson’s dust jacket depicts Peterson not long before his death, eyes empty, smile vague, dwarfed by the longest of long lenses. No field guides, no paint brushes, no birds in sight–just an old man pondering his legacy.

I’ll review Doug Carlson’s book soon in a final entry commemorating the Peterson centennial.