The would-be type of Audubon’s Smith bunting provides a troubling example of how specimen data can be corrupted in the chain of publication.

We know from Audubon himself that he saw this species alive only once, in 1820, when he failed to secure a specimen. Not until 1843 did he handle specimens in the United States, when birds collected in southern Illinois were brought to him in St. Louis; the specimens had been secured by John G. Bell and Edward Harris, not by Audubon, who stayed in the city during his companions’ two-week excursion.

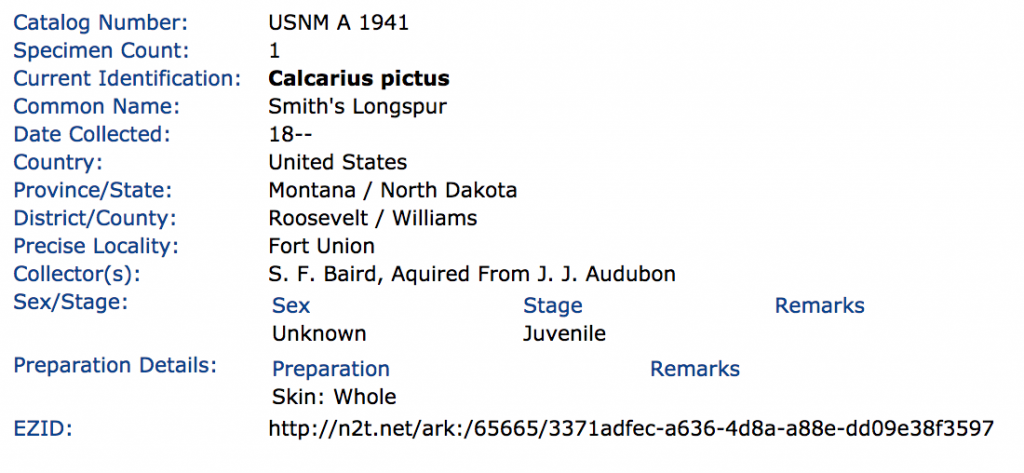

Nevertheless, with two of those skins on the table before him, Spencer Baird credited one to Audubon as collector — no doubt less a case of flattery (Audubon had been dead six years when Baird et al. published their Birds) than a poor solution to the difficulty of fitting all of the provenance information into the specimen chart.

More puzzlingly still, that skin, the single Bell/Harris example of the species apparently remaining at the Smithsonian, is now listed in the NMNH database as collected by Baird and received from Audubon — and deprived of its true date (April 1843), its true locality (Illinois, Madison County, near Edwardsville), and its true age (most certainly not a juvenile).

Innocent errors all, and no doubt easily resolved with another look at the specimen labels, but still a bizarre and instructive case of téléphone arabe in the history of ornithology.