Tomorrow marks the 150th anniversary of the death of Alfred Malherbe, one of those great French amateurs to whom we owe so many collections — and so many pretty books.

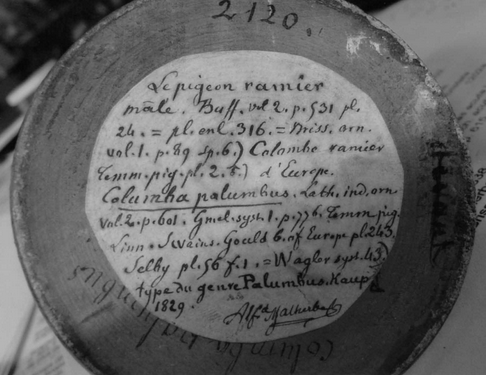

Malherbe was born on Mauritius on Bastille Day 1804, but returned with his family to their native Metz, where he was appointed to the bench at the age of 28. His real passion, though, was natural history, and over the last two decades of his life he served as director of the Metz museum and president of the Société d’Histoire naturelle de la Moselle, the eventual heritor of his own extensive collections.

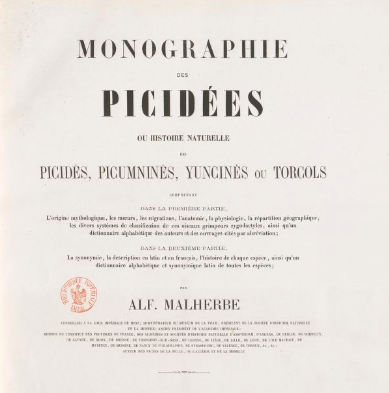

Malherbe is most famous today — if he is famous at all — for his Monographie des picidées, published in four volumes between 1861 and 1863.

More than 15 years in the making, the work was greatly lauded on its appearance. Félix Guérin-Méneville greeted the first livraison in the pages of the Revue et magasin de zoologie:

One can find nothing more beautiful than this work by M. Malherbe, and one can confidently state that in the perfection of its execution it exceeds anything that has been produced up to now in France or abroad.

The plates, prepared from paintings by Luc-Joseph Delahaye and others, Guérin-Méneville called “magnificent … of an accuracy and truthfulness in color and form such as one rarely finds in the most luxurious of works.” All of the considerable number of new species described by Malherbe are depicted the size of life.

Charmingly, and invaluably, Malherbe begins his text volumes with two chapters treating of woodpeckers and people — a subject worthy of an entire book in itself. We learn about Picus and Canente, Picumnus and Pilumnus, and the powerful love philtre known as jynx. Malherbe collects stories of superstition from the Romans to his own nineteenth-century day, accounts of the medical and venatorial use of woodpeckers and their parts, and, naturally, tales of rustic feasts built around the flesh of picids,

which they even claim is delicious…. But having been so curious ourselves as to taste the flesh of French great spotted and green woodpeckers, we share the judgment of Audubon … who affirms that the flesh is detestable, that it tastes strongly of formic acid and is extraordinarily disagreeable….

They may not be tasty, but Malherbe takes a firm stance on woodpecker conservation.

If one considers the terrible ravages committed in orchards, forests, and farms by the innumerable myriads of insects in their terrible swarms, one can ask whether on balance the woodpeckers, far from being harmful, are not rather extremely useful to the owners of forest and field by devouring an immense quantity of larvae, caterpillars, and insects of all kinds every day, particularly when they are feeding young…. Count up the number of fruit trees, especially peaches, that perish from [insect damage], and you will become indulgent of these birds that are the principal destroyers of such insects.

Gone, happily, are the days when there were bounties on the heads of sapsuckers and other woodpeckers — in part, perhaps, thanks to the beautiful work prepared by Alfred Malherbe.