On this first truly hot day of summer, I’m deep in thought about — what else — juncos.

As devilishly tricky as it can be figure out just what kind of junco you have before you, there has historically been little difficulty in distinguishing the juncos from other thick-billed ground-dwellers.

But there are exceptions.

Samuel Griswold Goodrich’s Illustrated Natural History of the Animal Kingdom is remembered today, if at all, almost exclusively for its inclusion of a number of dinosaurs, still a novelty when this encyclopedia was first published in 1859. In its late nineteenth-century day, though, Goodrich’s compilation (republished in 1872 as Johnson’s Natural History) was a standard reference for young people with an interest in zoology, and this was the book that inspired the estimable career of none other than Frank Michler Chapman, whose 150th birthday approaches next week.

Goodrich was nothing if not assiduous as a copier and compiler, and his sources (often credited, sometimes not) include many of the most important naturalists of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, from Buffon up to Goodrich’s own day. Every once in a while, though, even Goodrich nods.

For example, when it comes to the juncos.

Somehow, Goodrich conflates three quite different species in his discussion of the genus Struthus. He gives a perfectly recognizable, if concise, description of a slate-colored junco:

color bluish-black; abdomen and lateral tail-feathers white.

But he goes on to apparently synonymize S. hyemalis — the junco — with Plectrophanes nivalis, the snow bunting. The next portion of the description applies to that very different species:

it is a shy, timorous bird, seldom seen except during snow-storms, when it appears in flocks around the houses. At this it presents much diversity of plumage, some being almost white, and others partially white.

The summary of range and habitat also belongs to the snow bunting — at first.

It is a northern bird, common to both continents, being found as far north as Greenland, Spitzbergen, the Faroe Islands, and Lapland. It migrates southward, always by night, on the approach of winter, and some go as far as England and France in Europe, and Virginia in America.

But get this:

Although they mostly breed in high northern regions, still some nests are found in most of the northern Atlantic states,

a statement that can be read as applying only to the slate-colored junco.

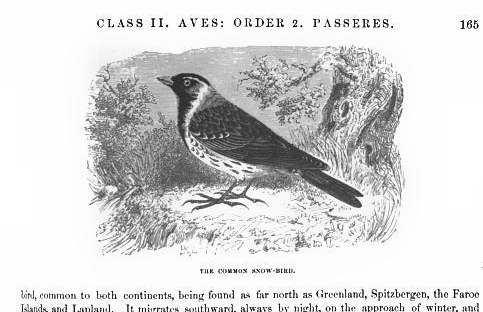

All that is confusing enough. But Goodrich goes on, keeping the promise proclaimed in his work’s title, to illustrate this “snow-bird.”

That’s not a junco, and it’s not a snow bunting. It is a common bird, and it is often found in snowy habitats, but I don’t think anyone, even 155 years ago, could really confuse a Lapland longspur with the other species in Goodrich’s jumble.

I doubt very much that the serious readers of the Illustrated Natural History were led significantly astray by this complex garble — which was repeated, words and picture alike, in the second edition. All the same, I’d love to see the young Frank Chapman’s copy of the book. I bet there’s an interesting note scrawled there.