It’s well known that the two sexes of the Williamson’s Sapsucker were originally described as separate species, a perfectly understandable confusion given the remarkable difference in their plumages.

What most of us don’t recall is that in the early nineteenth century another woodpecker was subjected to a similar, and similarly temporary, fate. Today we think of the Red-headed Woodpecker as absolutely distinctive, unmistakable in any plumage; but our forebears weren’t always so certain.

John Latham was the first to describe this puzzling bird, in the 1780s; he called it, logically, the White-rumped Woodpecker, and based the account in his General Synopsis on a specimen from Long Island, New York. Neither the collector, a certain Captain Davies, nor Latham himself quite knew what to make of it: as the latter wrote, this bird

has, till now, never come under my inspection. I have some opinion of it being a female, but of what species cannot ascertain; am therefore constrained to place it as a distinct species, at least for the present.

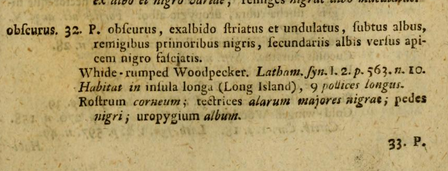

Johann Friedrich Gmelin, updating the Systema naturae at the end of that same decade, was less cautious. He copied out Latham’s description in Latin, then assigned the “Whide-rumped Woodpecker” its very own Linnaean binomial, Picus obscurus — in allusion, I’m sure, to the animal’s overall color, not to its ontological status.

Alexander Wilson, whose own connection to this species is the stuff of myth, was apparently unaware of Gmelin’s unwarranted multiplication of species; in the American Ornithology, he writes only — probably in reference to Latham, whose work we now know was available in Philadelphia — that the dusky plumage of the young birds “has occasioned some European writers to mistake them for females.”

It was up to Louis Jean Pierre Vieillot to point out the full error into which Gmelin had fallen:

As similar as the male and the female of this species are to each other in color, the immature birds differ from both sexes of the adult…. Latham and Gmelin created a redundancy when they presented the young bird as a separate species.

It was no doubt a specimen from Vieillot’s own collection that served as the model for Jean-Gabriel Prêtre’s illustration of the “Pic tricolor jeune”:

The matter, one would think, was closed. But Charles Bonaparte, while acknowledging that Vieillot had already made the point clear, still felt moved, twenty years later, to include an account of the Young Red-headed Woodpecker in his American Ornithology of 1828. In addition to a very thorough description to debunk this “nominal species,” Bonaparte “thought proper … to give an exact figure of it,” in the shape of the colored plate at the top of this page, by Alexander Rider. Bonaparte, always given as he was to extravagant enthusiasms, felt that Rider’s woodpecker

will perhaps be allowed to be the best representation of a bird ever engraved.

I’m not so sure about that (or rather, I’m quite sure about that). But it is a nice illustration from, and of, a time when even the familiar birds of America could provide a mystery.