Of all the great names from the generation of the DVOC‘s founders, that of Samuel N. Rhoads may be heard the least.

Even in this year of the sesquicentennial of his birth, Rhoads remains for most of us a dimly remembered name, encountered once or twice, perhaps, in Witmer Stone’s Old Cape May and then forgotten. A leading light a century ago in North and Central American ornithology, Rhoads now seems to be little more than a subject for local historians and eccentric “bloggers” who really should be working on something else.

Ironically, Rhoads may be better known today in the west than here in his native mid-Atlantic. His collecting tours of Texas and Arizona in the 1890s resulted in a number of records still cited today, and his pioneering trip to Washington and British Columbia was, until recently, commemorated each year by the late-summer “Rhoads Count” conducted by the Kootenay Naturalists.

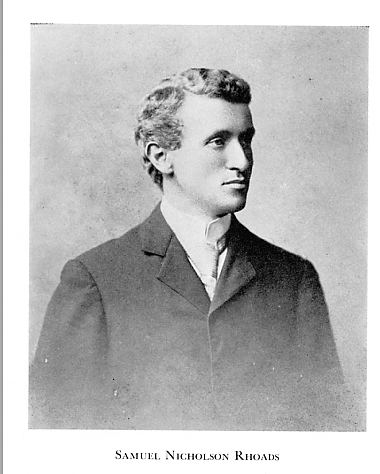

In addition to his attainments as a naturalist, Rhoads was a devoted historian of his field. Writes William Evans Bacon in the Cassinia obituary illustrated by the photograph above

Except for his labors, numerous records of great interest, particularly those pertaining to pioneer days, would have been irretrievably lost …. Rhoads amassed his information by extensive search through the literature, by the examination of museum specimens, … and by personal interviews with naturalists, trappers, trappers, old pioneers, and frontiersmen.

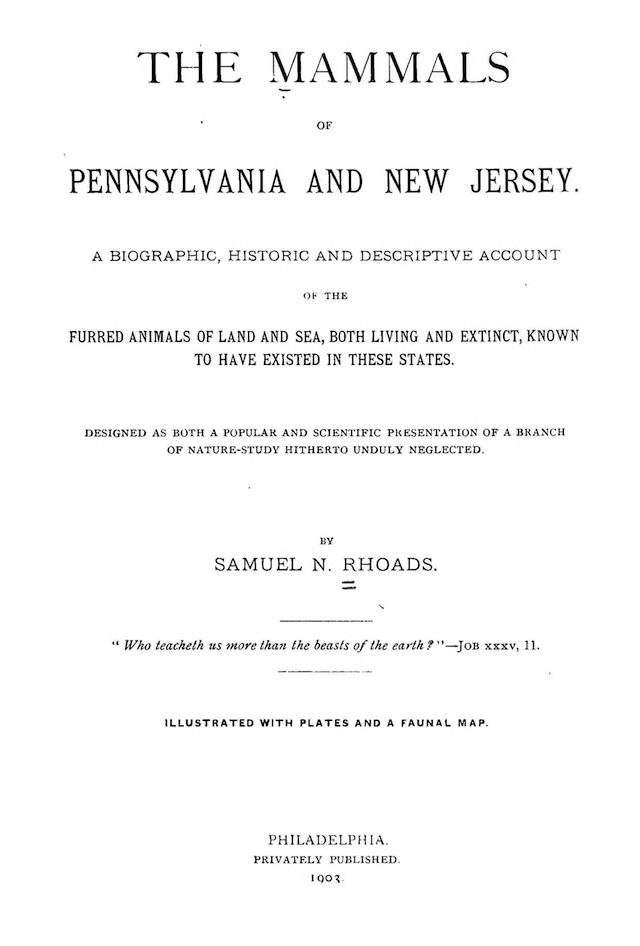

That historical interest was accompanied, inevitably, by the usual bibliophily, and in the first two decades of the last century, Rhoads owned a small Philadelphia bookshop and publishing house, its most notable productions facsimiles and reprints of such regionally important titles as the botanist William Young’s Catalogue and Ord’s American Zoology. In 1903, Rhoads printed his own most important work, The Mammals of Pennsylvania and New Jersey.

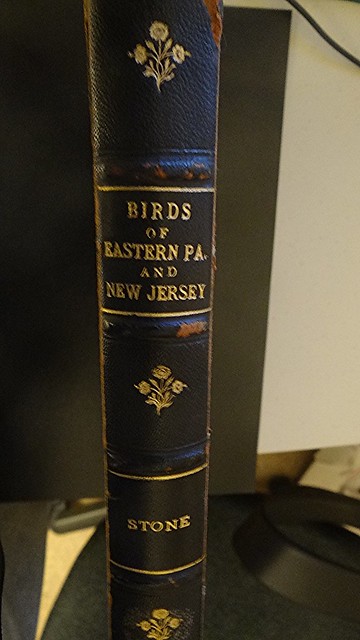

Given these predilections and pre-occupations, it’s no surprise to find that Rhoads’s own library was carefully assembled and, more remarkably, apparently curated with an eye to posterity. I don’t know where the collection ended up after his death, but one of the most interesting volumes, his copy of Witmer Stone’s Birds of Eastern Pennsylvania and New Jersey, is now in Firestone Library.

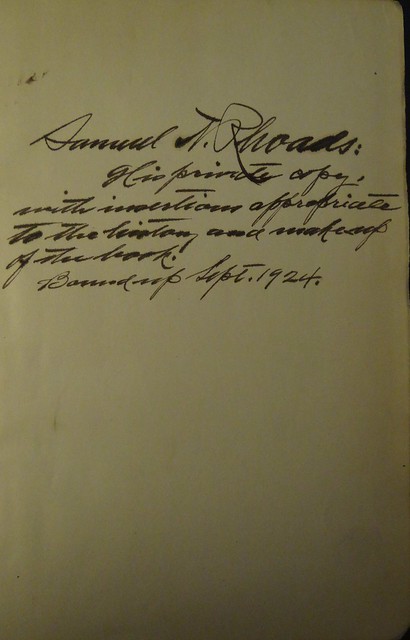

Rhoads was a member of the DVOC committee charged with overseeing the production of this work, and, as he wrote on the second flyleaf in September 1924, he saw his copy as a repository of documents bearing on the history of the Club and its most ambitious publication to date:

Samuel N. Rhoads: / His private copy, / with insertions appropriate / to the history and make-up / of the book. / Bound up Sept. 1924.

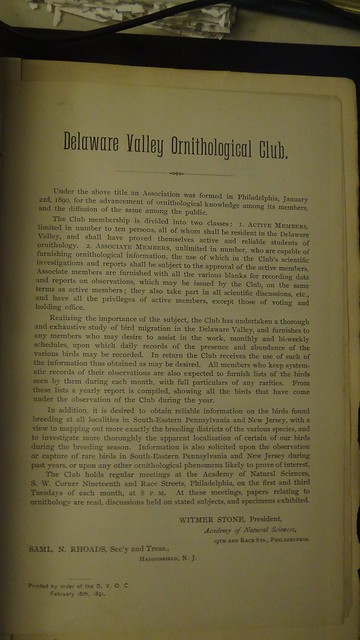

Among the documents inserted into Rhoads’s scrapbook are appeals for phenological information about the birds of the region, directed to the general public

and, no doubt more profitably, to “gunners and sportsmen” who might be able to furnish unusual records.

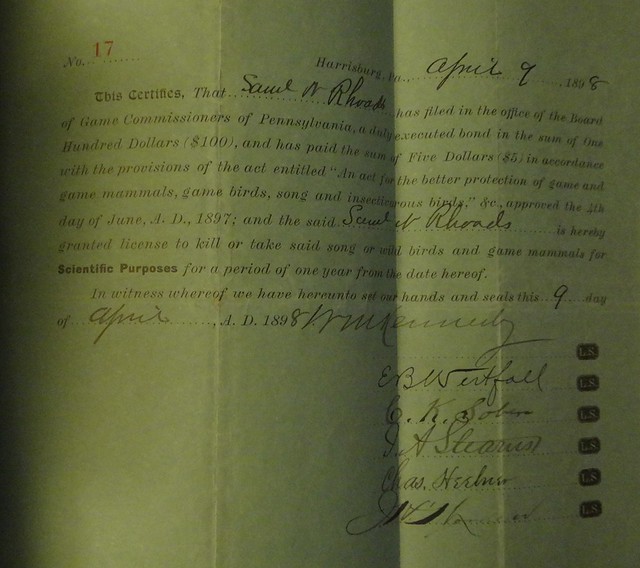

There are also more personal bits of history, including Rhoads’s collecting permit — “license to kill or take said song or wild birds and game mammals” —

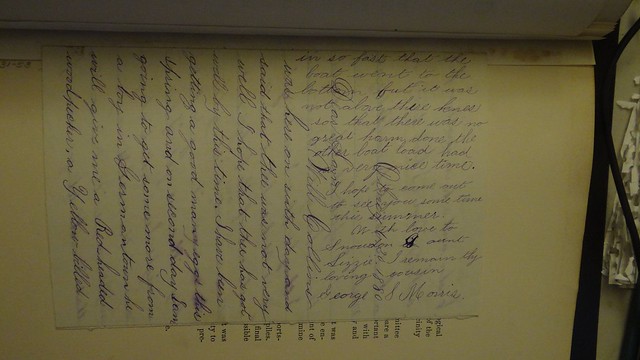

and a delightful letter in pale purple ink from his step-cousin George Morris, full of news of egg collecting and boating mishaps:

The general history of the DVOC is represented by a fine photo of this January 1898 meeting — taken exactly 85 years before the first women were admitted to membership:

Rhoads is number 23, his cousin Morris number 24; Stone, number 28, is seated at the table with the open book. In his handwritten key, Rhoads tells us that this self-same photo was used as “proof” for his 1902 Bird-Lore article and afterwards returned to him by Frank Chapman.

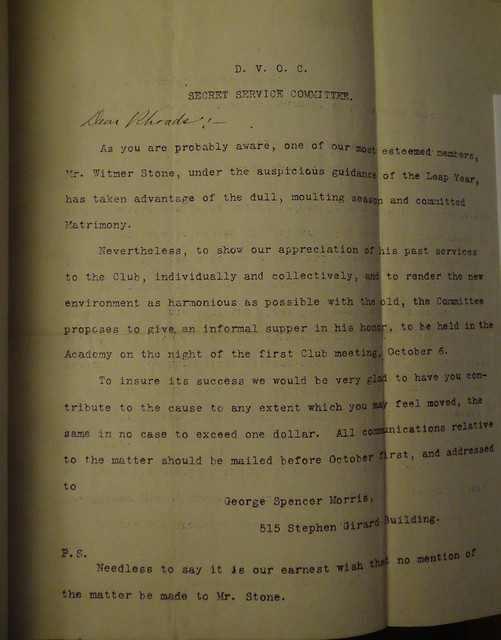

There are postcards and field lists, too, but the most wondrous of the ephemera preserved here is an invitation to a party for Witmer Stone on the occasion of his having “committed Matrimony”:

Two years after Rhoads had his little archive bound, there was an explosion and fire in his Haddonfield house. The books, obviously, survived, but Rhoads’s spirit did not: “conflicting currents of emotion” overwhelmed him, in Evans’s discreet phrase, and he spent the last quarter century of his life in seclusion, sometimes in confinement, until he died, sixty years ago today, leaving us this unique record of the early days of a venerable institution.