I can’t see it. No matter how many I’ve watched in the field, no matter how many skins I’ve handled, I just can’t see the green on a green heron. And I’m not alone: this name regularly shows up on those lists of “worst bird names of all time,” and I can’t count the times I’ve had to soothe sputtering colleagues in the field who, like me, can see blue and gray and purple and red, but not green.

It’s just a name, of course, and names don’t “mean” in the same way that real words do. There’s nothing to stop us from calling this bird the orange heron or the apricot egret or, for all I care, Hortense. Names can’t be “bad.”

But that doesn’t stop me from wondering why we call it green.

Hans Sloane seems to be the first European to have described this bird, which he encountered in Jamaica in 1687/88.

Sloane’s description of his “small bittern” leaves no doubt as to the species under discussion, but he has very little to say about his bird’s colors — and he never mentions any shade of green. He does half-apologize for the engraving:

I know not but that some part of the odd Position of the Neck may be owing to the carrying of it, after it was kill’d.

It was Mark Catesby who, in word and in picture, first convinced the scientific world that this bird was green.

A Crest of long green Feathers covers the Crown of the Head. The Neck and Breast of a dark muddy Red. The Back cover’d with long narrow pale-green Feathers. The large Quill-Feathers of the Wings of a very dark Green, with a Tincture of Purple. All the Rest of the Wing-Feathers of a changeable shining Green….

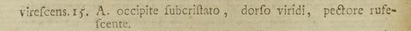

Given that description to rely on, it only made sense for Linnaeus to christen the bird Ardea virescens, “a heron with a somewhat crested crown, a green back, and a reddish breast.”

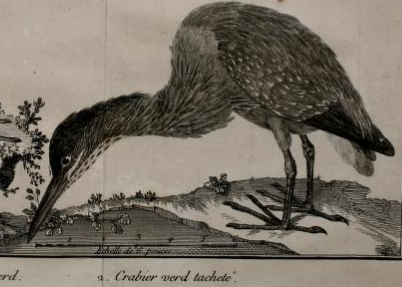

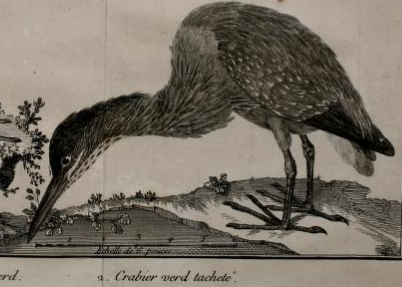

Catesby, like Sloane, still knew the species under the name “small bittern,” as Mathurin Brisson confirmed in 1760 in the Ornithologie. Rejecting the binomial Linnaeus had published two years earlier, Brisson assigned the bird the Latin label Cancrofagus viridis, which he translated in his French text as “le crabier verd,” the first time, so far as I know, that such a name was used in a European vernacular.

Martinet’s illustration is not what one might call overly successful, combining as it apparently does the body of a green heron with the legs and neck of another species or two. He does much better with the bird Brisson calls “le crabier verd tacheté,” occasionally considered in those long-ago days a distinct taxon or, later on, the female of the green heron. Martinet’s drawing is as delightful as it is readily identifiable, as a juvenile green heron.

Twenty years later, Buffon retained Brisson’s “crabier vert” in the heading for his account of the species, and he continued, too, to recognize the “spotted green heron” as a distinct species.

So far as I can tell, the first ornithologist to have rendered Ardea virescens or “crabier vert” in English was Thomas Pennant, in his Arctic Zoology of 1785. Not content just to call the bird “green,” Pennant goes lavishly, extravagantly out of his way to justify the name, describing the little wader as a

H[eron] With a green head, and large green crest … coverts of the wings dusky green, edged with white….

Pennant’s name appears to have been made canonical by its use in John Latham’s General Synopsis and Index ornithologicus. One holdout was William Bartram, who in his 1791 Travels used “green bitern” or “lesser green bitern” for the bird — an obvious nod in the direction of Catesby, whose itinerary largely inspired Bartram’s journey.

Bartram’s friend and disciple, Alexander Wilson uses the name “green heron” as the title of the species account in his American Ornithology; no doubt as a compliment to his patron, though, the text itself refers to the bird as “the Green Bittern.” Wilson also alludes in disgust to the “very vulgar and indelicate nickname” with which the bird is saddled by “public opinion”; “shitepoke” and similar names are still current today over much of this species’ US range, a rare example of the survival of a genuine folk name.

Bartram and Wilson were on the wrong side of onomastic history. It has been green heron ever since, except for that brief period when this species and the striated heron were “lumped” under the English name green-backed heron (intentionally or not, a direct translation of Linnaeus’s Ardea dorso viridi).

Once again, though, green heron it is, and green heron it will remain. Whether I can see it or not.