Remember how hard it used to be to gather image material for study or publication?

No, you probably don’t. I can barely recall those days of drudgery and trudgery myself, all that time in the library and on the telephone and at the post office. Now, it’s all (or much, with more every day) out there just a click away — a circumstance that keeps me wondering why on earth, in this year of sad commemoration, we haven’t assembled more of the pictorial record of the passenger pigeon.

Even Joel Greenberg’s now canonical Feathered River, which offers a good selection of images — not a few of them new to me — is limited by the constraints of print to scattered black and white photographs and a single sixteen-page gathering of color plates. Maybe Pinterest is the way to go after all.

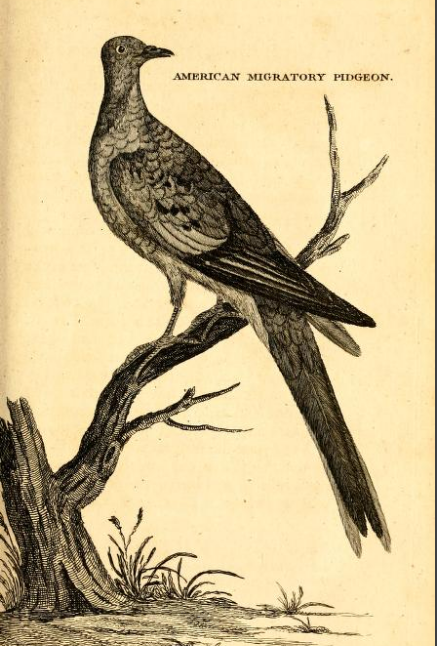

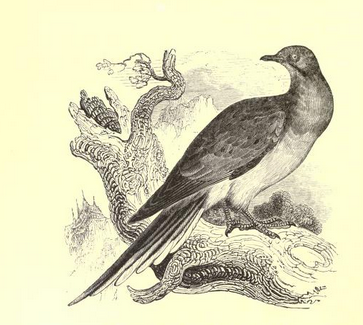

In any event, here are a few of the many images produced over the years and the centuries; critical remarks on some of them are offered in Schorger’s “Evaluation of Illustrations,” Chapter 16 in his Passenger Pigeon. I’ve forborne from posting the well-known plates by Wilson, Audubon, Fuertes, and Hayashi, all of which are widely and conveniently available.

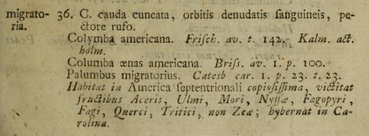

I make an exception for Mark Catesby, as many of the images credited on line and in print to his Carolina, Florida and the Bahama Islands are in fact from Seligmann. Here is the real thing, thanks to the Smithsonian Libraries and (again and again) BHL:

According to Schorger, Catesby’s painting was preceded some thirteen years earlier, “about 1700,” by the first European drawing of the species, in the Codex canadensis now attributed to the Jesuit missionary Louis Nicolas.

The text reads, in translation,

Oumimi, or ourité, or dove. One sees such great numbers of this bird at the first passage in spring and fall that it is incredible unless seen.

(Incidentally, Nicolas’s other work, the Histoire naturelle des Indes occidentales, which appears to be known almost exclusively to botanists, includes an entire chapter on the passenger pigeon, unmentioned, if rightly I remember, in Schorger and in Greenberg.)

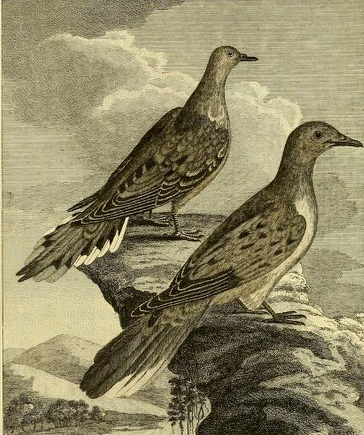

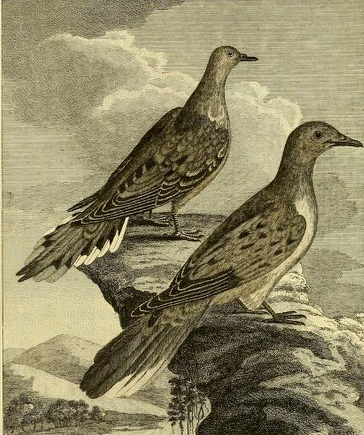

Thomas Pennant’s Arctic Zoology poses a passenger pigeon alongside its smaller cousin, the mourning dove:

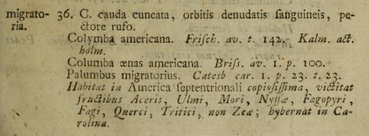

Mathurin Brisson rightly praised Johann Leonhard Frisch’s plate in the Vorstellung as “icon accurata”:

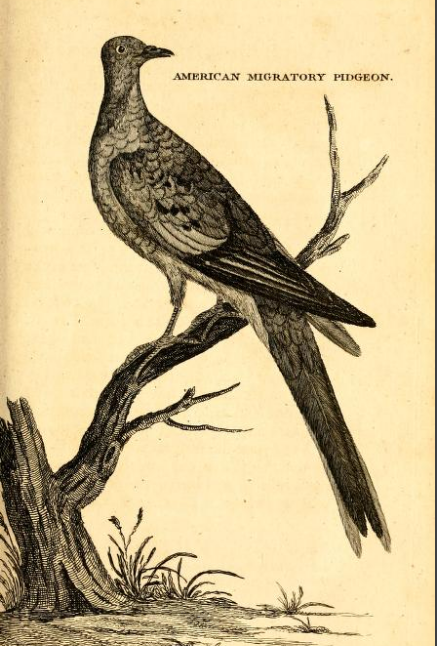

He could also have mentioned that it is one of the loveliest depictions of the bird ever published, a distinction that separates it vastly from the raggedy pigeon shown in Forster’s translation of Kalm’s Travels:

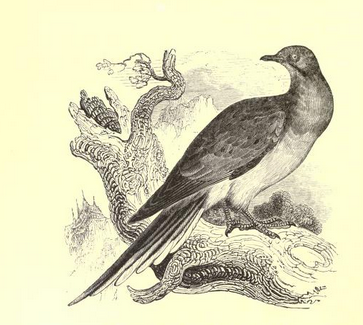

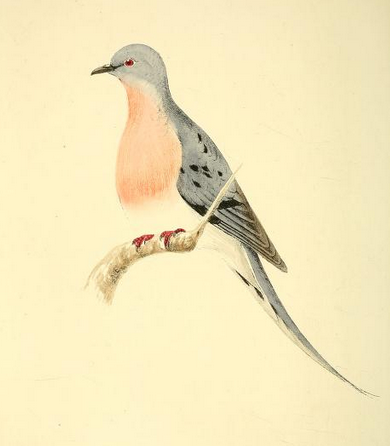

Surprisingly, E. Lear (I assume that E. Lear) was hardly more successful in the pigeon he drew for Prideaux John Selby’s Pigeons.

I can’t say that the figure in the Planches enluminées is too much better.

Eyton gets it closer to right in his History of Rarer British Birds.

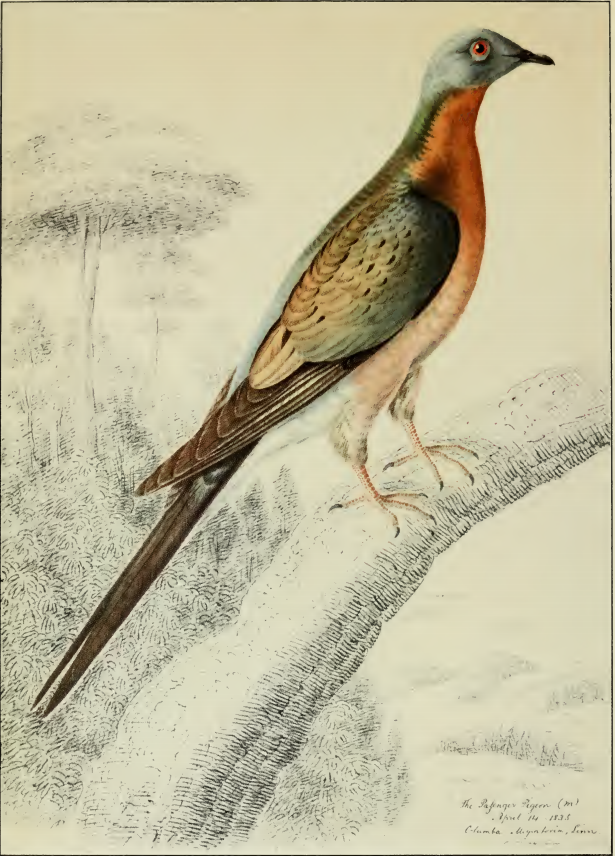

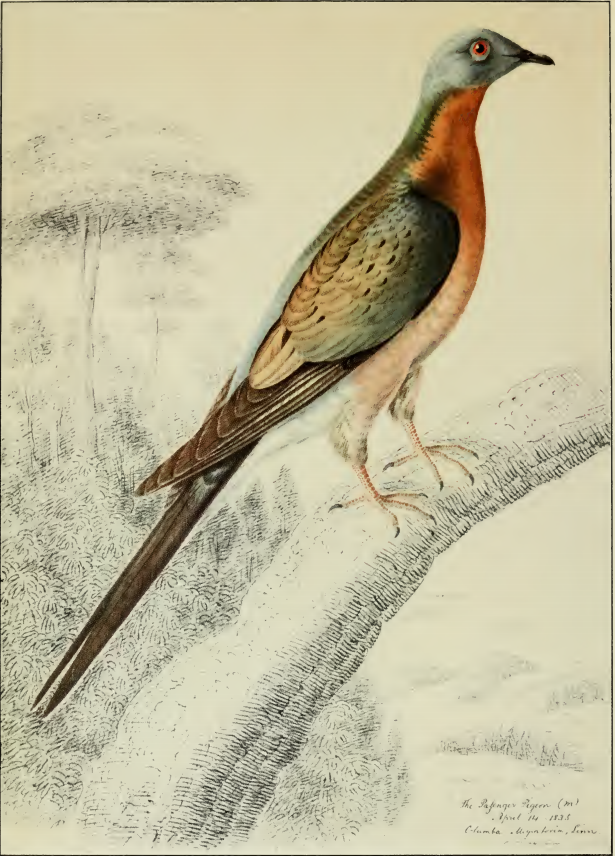

William Pope painted his bird in 1835.

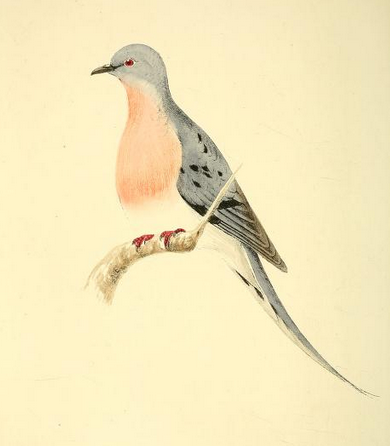

From earlier in the nineteenth century, the notorious Pauline Knip’s pigeon pair is decorative, but both birds are too obviously dead and stuffed for my taste.

Both sexes are also shown in De Kay’s Zoology of New York:

Henry Leonard Meyer’s colored portrait, almost two hundred years old now, has an orientalizing lightness to it that still appeals to my twenty-first-century eyes (Schorger, a sterner critic than I am, says “no merit as to drawing and coloring”).

Copied and imitated and plagiarized again and again, the appealing woodcut in Thomas Nuttall’s Manual seems familiar even to eyes that have never seen it.

It is not clear to me just who is responsible for the plate in Morris’s History of British Birds, whether Alexander Lydon or another painter; in any event, this is not a work many artists would rush to claim.

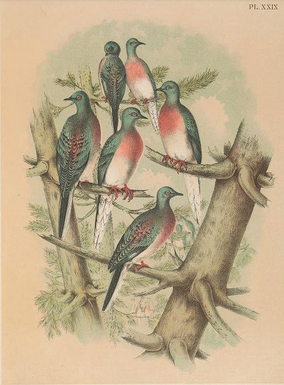

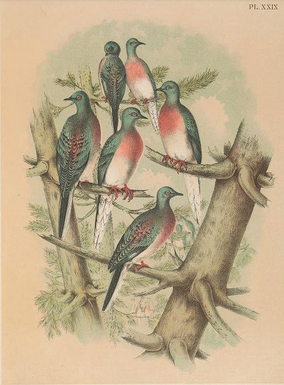

Still, it’s better than the infamous image of half a dozen shockingly colorful, big-footed birds in Studer:

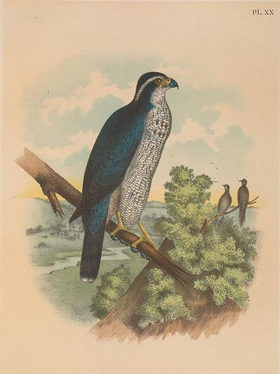

I prefer the justifiably wary birds in the background of this plate from the same work:

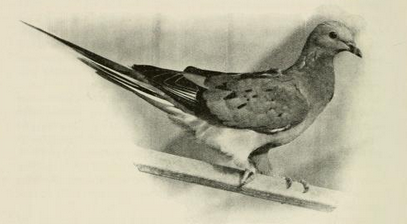

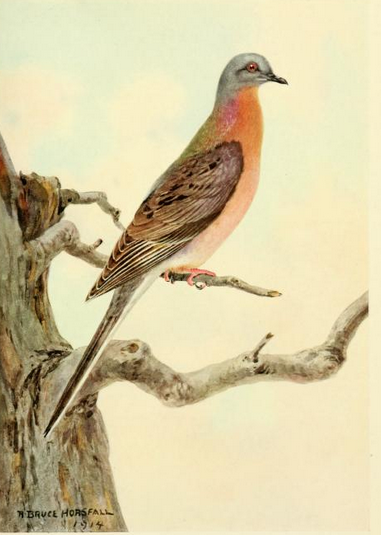

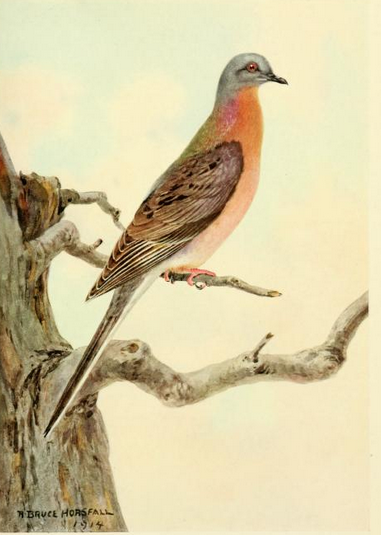

Published in the same year as the death of the last pigeon, Bruce Horsfall’s bird looks a bit too much like a mourning dove, I think.

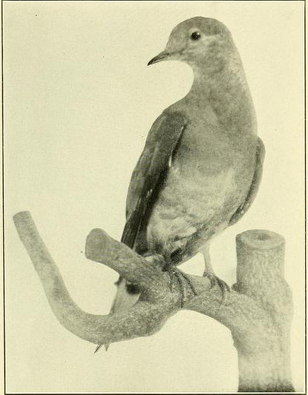

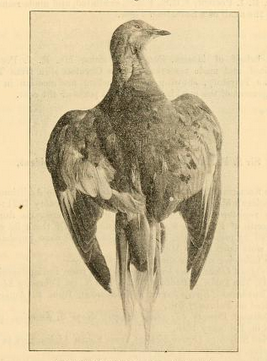

The passenger pigeon survived, at least in dribs and drabs, well into the age of photography. Martha, the last known individual of the species, may have been the most pictured of all individual American birds before the invention of the digital camera.

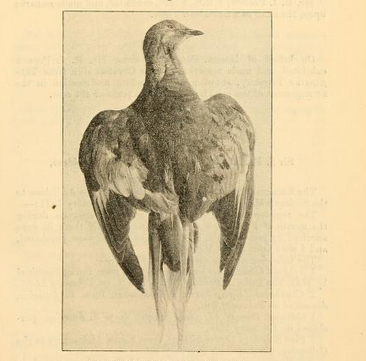

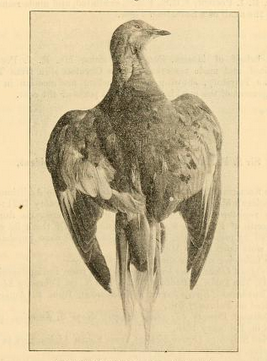

One of the last photographs of the dead Martha, taken by Robert Shufeldt while the corpse was still intact:

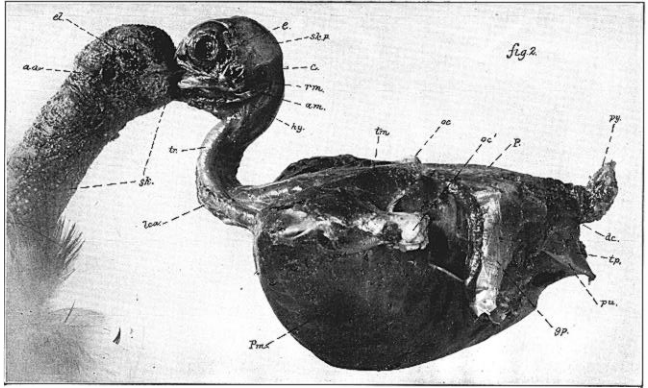

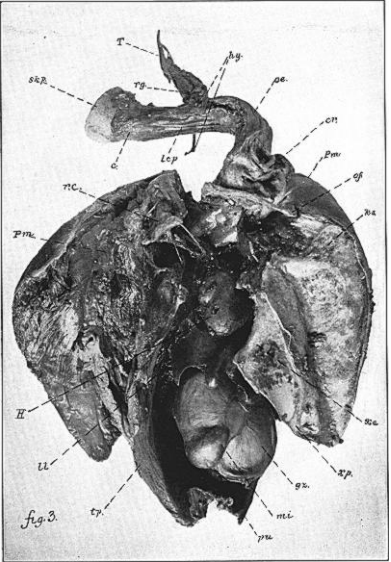

The shutters didn’t stop clicking here. Sometime between now and September, I’ll post some of the published photographs of the dissection — memento mori.

Meanwhile, are there interesting and useful images I’ve missed?