Do you ever get the feeling that the nineteenth-century world was so small that anyone who was anybody inevitably bumped into everyone who was somebody? In the ornitho-realm, think of Alexander Wilson and John Greenleaf Whittier — or John James Audubon and virtually every single one of his notable contemporaries.

Most such meetings were felicitous encounters, but late the night of June 17, 1841, two ornithologists bumped into each other in the worst possible way. As The Tablet reported, that afternoon

the Pollux, a new and very pretty steamer, left Civita-Vecchia with every promise of a most delightful passage to Leghorn. As evening closed in the daylight failed, but the night was pleasant, the sky serene and starry, the sea calm and smooth. These circumstances had fortunately induced many of the passengers to sleep on deck. About an hour before midnight, some one being still awake noticed a vessel approaching, and already so near as to cause alarm. It was some time before any one could be found to look to the danger — and when perceived, the vessel was only just turned with its broadside forward when the other vessel, also a steamer, ran into her amidships, with a shock that threatened instant destruction to both.

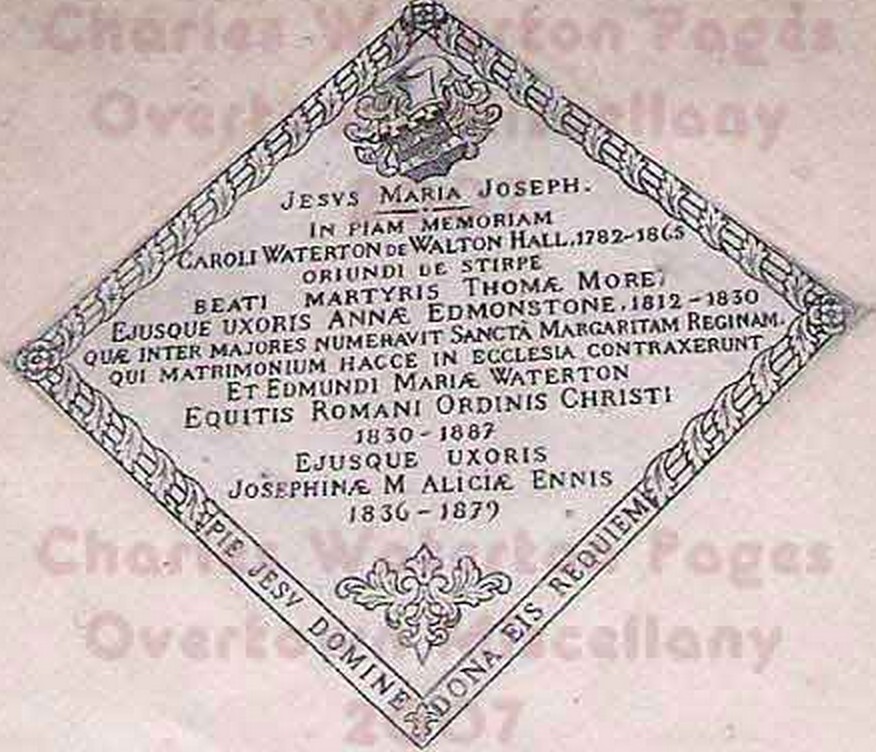

The Yorkshire naturalist, ornithologist, and taxidermist Charles Waterton was on board the Pollux with his sisters-in-law and young son:

it was evident that she had but a very little time to float. I found my family all around me; and having slipped on and inflated my life preserver, I entreated them to be cool and temperate, and they all obeyed me most implicitly. My little boy had gone down on his knees, and was praying fervently to the blessed Virgin to take us under her protection, while Miss Edmonstone kept crying out in a tone of deep anxiety, “Oh, save the precious boy, and never mind me!”

Waterton and his family, and indeed all but one of the passengers on the Pollux, were indeed rescued. Credit for averting total destruction went to — get this! — Charles Bonaparte, who just happened to be on the Mongibello when that ship so quickly sank the Pollux:

Had it not been for Prince Canino, Charles Buonaparte, it is more than probable not a single soul would have been saved. The Pollux would have been literally cut in two had he not had the paddles of the Mongibello reversed; the Mongibello could not have got the passengers to her deck in time had not he seized her helm, and brought her alongside the sinking vessel, which, within fifteen minutes after the first shock, had disappeared.

According to Waterton, his princely colleague’s ministrations continued even after the Mongibello and its shipwrecked passengers reached the harbor at Livorno:

Prince Canino pleaded our cause with uncommon fervor. He informed [the port officials] that we had had nothing to eat that morning…. He described the absolute state of nudity to which many of the sufferers had been reduced, he urged the total loss of our property, and he described in feeling terms the bruises and wounds which had been received at the collision…. The council of Leghorn relented, and graciously allowed us to go ashore.

Waterton would never forget the bravery and generosity of the Franco-Italian ornithologist, and neither should we.