On his long journey through the West Indies in 1888, the Canadian cleric Léon Provancher attended a reception in Trinidad at the home of the eccentric Sylvester Devenish, where he made the acquaintance of Dr. Léotaud, “an island celebrity of whom I had already heard,” and his son-in-law, also a physician.

Provancher, fully absorbed in his host’s collections of engravings, bronzes, photographs, relics, and “ornaments of all kinds,” has no more to say about the medical men in attendance, but I want to believe that they were relatives of an even more celebrated Trinidadian, Antoine Léotaud, author of what remains nearly 150 years after its publication one of the best and most ambitious, if necessarily imperfect, neotropical ornithologies ever written.

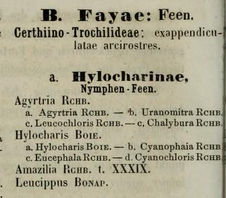

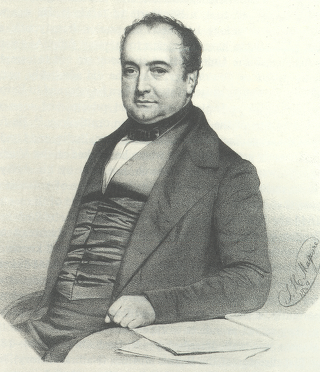

According to an obituary quoted by Junge and Mees, Léotaud was born on Trinidad 200 years ago this New Year; he studied the sciences in Paris, eventually taking a medical degree, and returned at the age of 25 to practice in Trinidad. Léotaud’s Oiseaux was published a year before his death on January 23, 1867 from “a painful malady of fourteen months’ duration.”

I don’t know whether it is poor health, frustration at his lack of scientific resources, or a literary tristesse tropicale that is to blame for the striking tone of disappointed nostalgia that Léotaud affects in the Oiseaux.

It would be the most offensive of positivisms to draw conclusions about Léotaud’s “real life” from the attitudes he strikes in his writings. But consider the fact that in 1865, while he was hard at work on the ornithology, Léotaud was awarded the gold medal of the Medical Society of Ghent for a study entitled “Sur les causes de dépérissement des familles européennes aux Antilles” — on the sources of degeneration in European families in the Antilles.

Somebody clearly missed Paris.

Whatever Léotaud’s own state, he had some pronounced ideas about the emotional and intellectual condition of the wild birds of Trinidad.

The Black Vulture, for example, moves in ways

destitute of gracefulness, revealing the bird’s insignificance; even its anger results in nothing more than an exhaled grunt which evinces its stupidity; its quarrels, lacking in energy of any kind, bear the sign of weakness…. Even in the pleasures of love it exhibits those sad characteristics that it reveals in everything else; it is silent, it is clumsy, its preparations are tedious and only with great effort does it manage to accomplish that act that is normally so effortless in almost all birds.

Projection? Pathetic fallacy? Or just a bad mood?

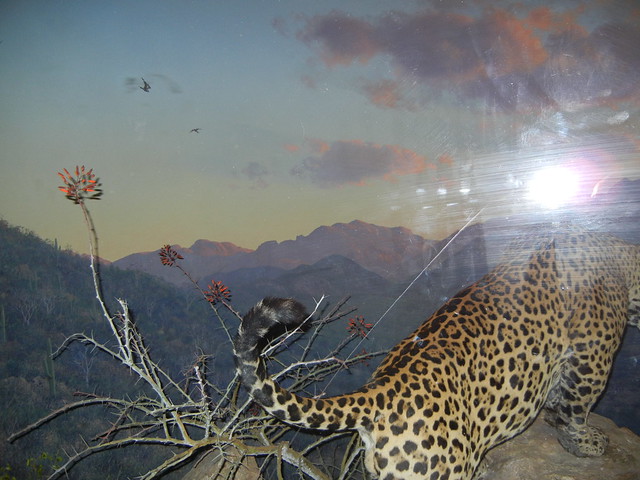

Léotaud writes with greater sympathy of the Snail Kite (the photograph here is from the South American continent — we did not see the species on our visit to Trinidad and Tobago).

This bird is rarely seen here…. It is always alone, no doubt because it finds no companions…. only a few individuals come to visit us around the month of July, and thus they find themselves in conditions contrary to their usual habits.

Loneliness, in fact, seems to be a problem for many of the birds of Trinidad, if we trust Léotaud. The poor little Tropical Screech-Owl sings a song that

inspires sadness, as this bird is heard only when everything in nature is ready for slumber; its song ushers in the dusk. No doubt he is calling his companion in this way….

Even the beautiful Trinidad Motmot moves Léotaud to melancholy contemplation:

He prefers the dimness of our forests, which seems to suit so well the sluggishness of his movements and the sadness of his call. Having perched for a long time on a branch, he leaves it only with reluctance. Even the fires of love can barely raise him above his apathy. His call … is in no way meaningful; it is a call not of gaiety, or of anger, or of passion. And beyond that, his posture is heavy, his shape graceless… he draws attention only with his tail, [the shape of] which is one of those secrets that man will no doubt never manage to unravel. The female accompanies him almost always, but she is incapable of bringing animation to his so sad life.

Yes, motmots are notoriously calm, but rarely have they been accused of having a flat affect. The reproach makes even less sense when Léotaud turns it on the flashy Rufous-tailed Jacamar:

he remains immobile for hours at a time, and hardly stretches out his beak to grab an insect that happens to stray within his reach…. His call is weak and plaintive…. His companion follows him almost always to share this life that seems so sad and monotonous.

The most poignant case of all seems to be that of the Green Honeycreeper.

I’ve always found these sturdy little frugivores a colorful delight, but Léotaud had a different impression:

Its form is not very graceful, and its posture is somewhat heavy…. Its plumage is worthy of admiration, but its weak, insignificant call draws no notice. He is not made for captivity, and deprived of his liberty, he soon converts his cage into a tomb. Nevertheless one can accustom him to his prison, but only at the cost of so much effort and patience that it is a triumph of which only some people are capable, namely those whose interest in birds is a true passion.

It is harder and harder not to imagine that the author is speaking of himself and his own circumstances in such descriptions.