It’s mildly old-fashioned now, I think, but “Alice” was all the rage in the nineteenth century, a naming fad inspired in Britain, Germany, and the US by Alice Mary Maud, daughter of a British empress and mother of a Russian one. (I am married to one of her more recent namesakes, born of British and Hessian parents almost a hundred years after the Grand Duchess’s death.)

The popularity of the name coincided with a great boom in descriptive natural history, and today there are dozens, no, hundreds, of plants and animals named for one Alice or another. There’s the Alice sundew, the Alice wood-boring beetle, the Alice cream-spotted frog, and on and on. There are even a few birds.

A quick look at the Handbook of Birds of the World turns up something like twenty species named for an Alice, among them –unsurprisingly — four hummingbirds. One of them is the threatened Purple-backed Sunbeam, Aglaeactis aliciae.

This lusciously beautiful Marañón endemic was first met with by the German collector Oscar Theodor Baron, who in March 1894 found several of the birds in Succha, Peru, “above an elevation of 10,000 feet … feeding from parasitic flowers which abound on alder and other trees.” Before returning to Europe himself, Baron divided the large collection he made in Peru into two lots, “containing many novelties” besides this hummingbird, and shipped one set of specimens to Walter Rothschild, the other, jointly, to Frederick DuCane Godman and Osbert Salvin, then some 35 years in to their collaboration on the vast Biologia centrali-americana.

When Salvin published the formal description of Baron’s new hummingbird in early 1896, he named it Aglaeactis aliciae. Alice’s Sunbeam, a pretty name. But he didn’t bother telling us who Alice was

James Jobling’s unbeatable Dictionary, our first and usually last resort in such questions, identifies the mysterious eponym as

Alice Robinson (fl. 1895) wife of US collector and explorer Col. W. Robinson.

Although that suits chronologically, there’s a problem.

Not only have I been unable to retrace Jobling’s path to that conclusion, but the one hummingbird we know absolutely to have been named for that particular Alice goes unmentioned in the Dictionary, suggesting some confusion. And nowhere have I found any evidence that Salvin knew either of the Robinsons.

So it’s back to the drawing board, which in this particular case is already covered by a messy sketch of a very large haystack and a very slender needle.

Baron, the collector of the first specimens of the sunbeam, remains a little known figure even in lepidoptery, his apparent specialization. It would be almost as nice for us as for him if he was happily married to a lovely Alice, but I can discover no mention of any matrimonial circumstance anywhere in any of the sparse documents available from his life. Arguments ex negativo are the most dangerous kind, but there is further, if equally circumstantial, support for the belief that this well-traveled naturalist was without an help meet to him. See what you think of this.

In 1893, Salvin had described another hummingbird taken by Baron as Metallura baroni, the Violet-throated Metaltail. Had there been a wife in the picture, I suspect that Salvin, gallant Victorian gentleman that he was, would have honored her rather than her husband, if by nothing more then at least naming the bird baronae.

That’s a slim straw to grasp at, but there’s more. Ernst Hartert, Rothschild’s curator at Tring, named two hummingbird species for Baron, a Eutoxeres sicklebill in 1894 and a Phaethornis hermit three years later. Both bear the epithet baroni, a potentially inexcusable slight — and one that would certainly have been avoided by Claudia Hartert, co-author with her husband of the description of Eutoxeres baroni.

The Baron’s Superciliated Wren, described by Hellmayr, and the Baron’s Spinetail and Yellow-breasted Brush-Finch, both named by Salvin, all commemorate a masculine eponym, too. Either Mrs. Baron did not exist, or she had somehow made herself persona non grata with much of the ornithological establishment of her time.

What about Osbert Salvin? We know that he was married, but we also know that his wife’s name was Caroline Octavia Maitland, and that they had one daughter, Viola. No jesuitical squirming and wriggling required here: our Alice was clearly not a member of Salvin’s immediate family.

But we’re not out of possibilities yet.

Recall that though Salvin was the author of the formal description of Baron’s new sunbeam, the specimens were not his alone. In the Novitates Zoologicae for February 1895, Salvin wrote that

during the past summer Mr. Baron, who is now traveling in Peru, sent to Mr. Godman and myself his first collection of birds made during the first half of the year 1894 in Northern Peru.

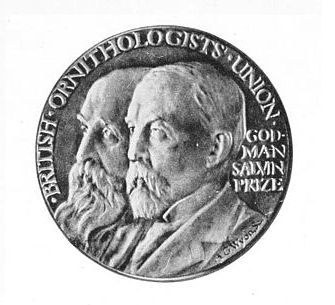

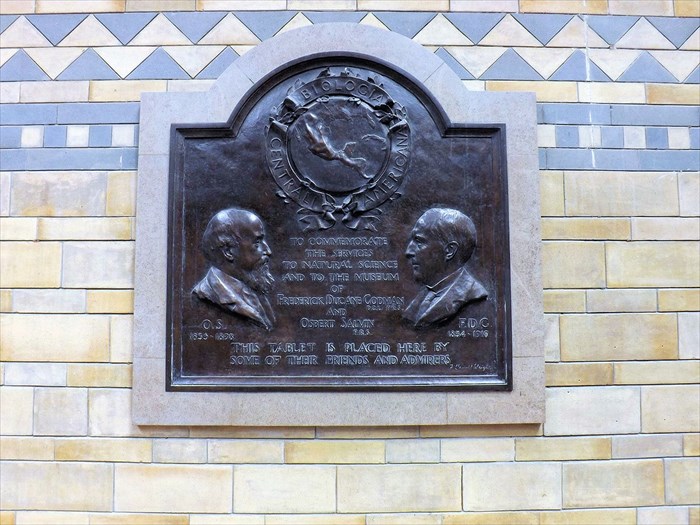

Godman and Salvin were the powerhouse natural history team of the second half of the nineteenth century.

In August 1923, on the occasion of the unveiling of a memorial tablet to the men, Science described their relationship:

these two distinguished men of science were intimately associated in research and the results of their labors form an important part of the treasures of the Natural History Museum. The friendship between them dated from the fifties of the [nineteenth] century, when they were both undergraduates at Cambridge, and lasted until the death in 1898 of Salvin, who was survived twenty-one years by Godman, the latter dying in 1919, in his eighty-sixth year. In 1876 [probably much earlier] the two friends conceived the idea of the monumental work entitled Biologia central-americana, which has been described as without doubt the greatest work of the kind ever planned and carried out by private individuals.

In 1885, Godman and Salvin decided to donate the specimens and library gathered in the course of their work on the Biologia, which they owned in common, to the British Museum; Science reports that the combined collection comprised more than 520,000 — that’s more than half a million — bird skins.

The memorial to the two ornithologists had been paid for by subscription. So great was the respect for their work that more contributions had been received than needed:

Lord Rothschild, in presenting the tablet on behalf of the subscribers, explained that the committee had decided that any subscriptions left over after the memorial had been paid for should be devoted to a collecting fellowship…. Such names, such acts, such memories and such lives should not be forgotten by those who looked at the specimens and collections the museum contained.

The Godman family agreed:

a further sum of £5,000 [was donated] to the Godman Exploration Fund

by his two daughters, Edith and Eva, and by his widow.

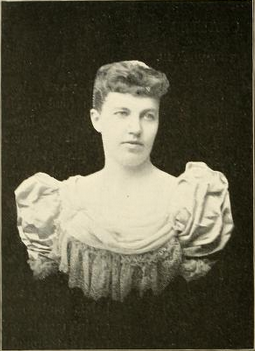

His widow: Dame Alice Godman.

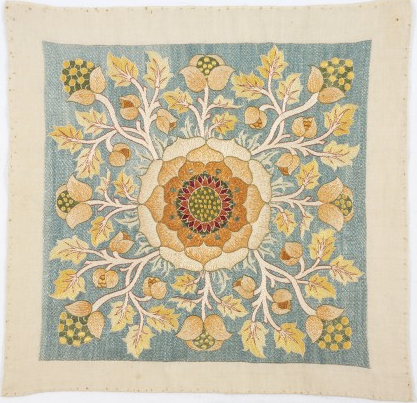

According to the dedication page of the Biologia, Dame Alice took “the deepest interest” and offered “much assistance and sympathy in the completion of this work.” I know nothing of her ornithological pursuits, but she had considerable enthusiasm for botany and gardening, providing a subvention for the publication of Elwes’s Monograph of the Genus Lilium and lending her name to several plant species, some of which can still be seen on the grounds of the former Godman estate. She and her husband traveled very widely, in the New World and the Old, even joining a paleontological expedition to Africa.

She was also a skilled needleworker,

a founder of the British Girl Guides, and Vice-President of the Horsham Division of the British Red Cross during the First World War.

I think it more than likely that Salvin named the sunbeam for this Alice, his friend and colleague’s wife, who had borne their first child in summer 1895 (and would have the second at the end of 1896). Anyone with access to the correspondence between Salvin and Godman should be able to prove that supposition with ease. Meanwhile, I think she deserves her hummingbird, Aglaeactis aliciae. Don’t you?

![2009 Top One Hundred Countdown # 1: Cabinet Card---Mrs. Wirt Robinson (Anita Alice Mathilde (Phinney) Robinson) [Brought Forward For Pure Greatness]](http://farm4.staticflickr.com/3435/3980086523_29d436d19a_z.jpg)