I’ve always thought it nicely appropriate that we should celebrate Edward Sabine‘s birthday just at the time of year when his most beautiful namesake is exciting so many birders on its southbound passage.

Sabine would be 225 years old today. In 1818, at the age of 30, he was recruited to serve as the astronomer on the Ross Expedition in search of the Northwest Passage. A scientist of wide-ranging interests — he would later be elected President of the Royal Society — Sabine made a point during his time in the Arctic of collecting birds, among them specimens of an unknown small gull. The circumstances were described by his brother, Joseph Sabine:

They were met with by [Edward Sabine] and killed on the 25th of July last on a group of three low rocky islands, each about a mile across, on the west coast of Greenland….

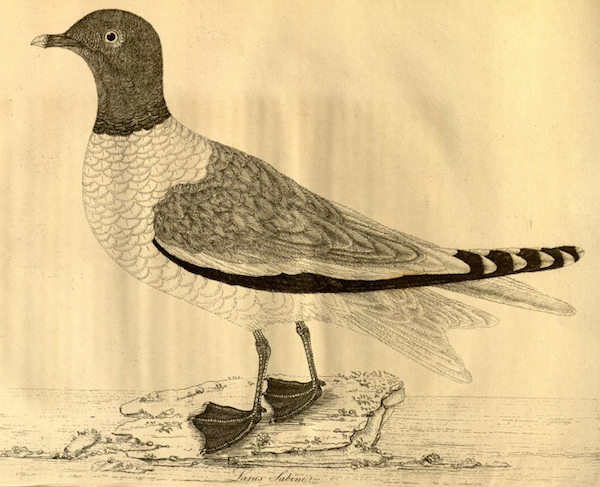

Joseph Sabine, “in conformity,” as he said, “with the custom of affixing the name of the original discoverer to a new species,” named the new gull Larus Sabini.

It was an understandable gesture, but the name has exposed the Sabine brothers over the years to occasional sniping by those who believe that Edward Sabine had named it for himself. He didn’t, and I leave it up to you to decide whether you think Joseph Sabine was looking for a bit of vicarious immortality in his choice of names.

Among the many other honors accruing to him over a very long lifetime, Edward Sabine would later be also commemorated in the name of those very islands off western Greenland where he shot the first gulls. As a result, the Sabine’s Gull is one of the most onomastically overdetermined birds around:

English name: Sabine’s Gull

Scientific name: Xema sabini

Original collector: Sabine

Original describer: Sabine

Type locality: Sabine Islands.

It makes it very easy to remember.