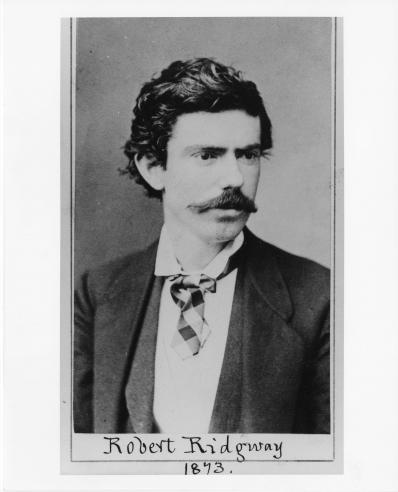

It was two centuries ago this summer, just a year after the death of his “ever-regretted friend,” that George Ord published the first scientific description of the bird he honored with the name of the Wilson’s plover.

Ord commemorated his late colleague in both the English name and the scientific name of the new species, assigning it the Linnaean binomial Charadrius wilsonia. Ten years later, he changed his mind. Not about Alexander Wilson’s considerable merit, and not about the suitability of “this neat and prettily marked species” as a monument to the American Ornithologist; but rather about the proper form of the bird’s scientific name. In the second edition of Volume Nine, and then in the three-volume edition of Wilson’s work published in 1829, Ord — accepting without comment a change first made by Vieillot in 1818 — alters the epithet, from his original wilsonia to wilsonius.

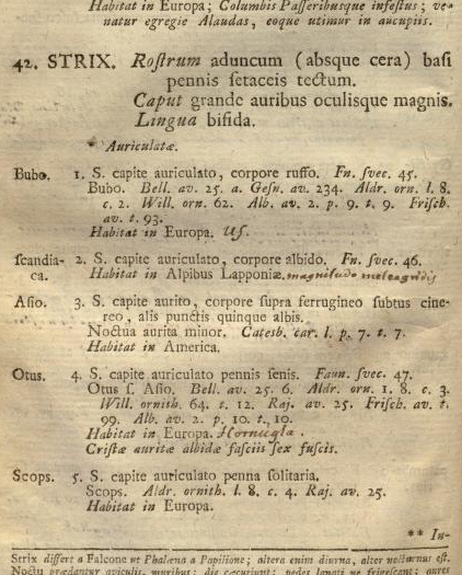

Alters and corrects, I should think: Charadrius is a masculine noun, and so any adjective modifying the genus name — from vociferus to nivosus, from thoracicus to modestus — should itself be masculine — and thus, Charadrius wilsonius it is. Sometimes. And sometimes not. The currently recognized scientific name of the Wilson’s plover is — if we follow the AOU, the SACC, Clements, the IOC, Howard and Moore — Charadrius wilsonia, just as it was in Ord’s 1814 description. Why? It all started, I think, in 1944, when the Committee responsible for the preparation of the fifth edition of the AOU Check-List — long delayed, “in part due to the war” and the attendant shortage of good paper — published a preliminary digest of the changes to be expected whenever that edition might appear. Among the principles propounded: where in the fourth, 1931 edition any “obviously” adjectival specific names were made to agree in gender with the genus name, in the new edition

original spellings will be used in all scientific names.

When the fifth edition was published, in 1957, that pronouncement was furnished with an important exception:

specific and subspecific names used as adjectives have been made to agree with the gender of the genus,

just as had been the case before 1944. Oddly, though, that exception was not applied to the plover, which on being returned after some decades of exile to the grammatically masculine genus Charadrius, nevertheless retained, and retains today, the grammatically feminine epithet wilsonia.

This combination, officially sanctioned though it be, is not only barbarous, but contravenes the ICZN, whose principles and decisions the AOU expressly follows in matters of naming. While priority remains the highest of principles, the Code tells us that

a species-group name, if it is or ends in a Latin or latinized adjective or participle in the nominative singular, must agree in gender with the generic name with which it is at any time combined (31.2)

and that

if the gender ending is incorrect it must be changed accordingly (34.2).

If I read this correctly, then the name of the Wilson’s plover should rightly be Charadrius wilsonius Ord 1814; wilsonia should be rejected as improperly formed. Unless, of course, the ICZN has issued a special dispensation permitting the retention of the ungrammatical name. I can’t find such a document, but maybe it’s out there — or maybe I’ve missed something obvious.

I do not, by the way, buy the explanation offered by some — most recently endorsed in the new Howard and Moore — that Ord’s “wilsonia” was not adjectival. The change to “wilsonius” in 1824 (and earlier in Vieillot) is proof enough that Ord understood the word to be a first-and-second declension adjective — and that obviously renders inapplicable the ICZN’s provision (31.2.2) covering equivocal species epithets:

Where the author of a species-group name did not indicate whether he or she regarded it as a noun or as an adjective, and where it may be regarded as either and the evidence of usage is not decisive, it is to be treated as a noun in apposition to the name of its genus.

Does anyone know who decided, when and on what basis, “wilsonia” was a noun? What am I overlooking here?

Fill me in.

On the 201st anniversary of the death of Alexander Wilson — with thanks to David and Ted for good discussions.