The Lister’s Punctilio

I don’t like grocery shopping. At all. But Alison is even busier than usual this time of year, so it has been my lot of late to be dodging cars in parking lots and carts in narrow aisles. No fun at all.

This morning’s expedition was better, though. As I stepped out of the car, senses alert, a big black bird flew across low: a common raven. No longer rare, no longer unexpected, this species is always great to see, especially in the urban wilds of northern New Jersey.

But here’s my dilemma.

Brookdale Park is just two blocks from our local Shoprite (grocery store names!), and the tops of its tall old oaks and tulips dominate the view to the west. Which is where this morning’s raven came from.

Brookdale happens to be the only site for which I am keeping careful lists nowadays. And I’ve been expecting a common raven to show up.

But I can’t “count” this one for the park. Neither the bird nor I was in or over Brookdale at the time of the sighting, so the gap in the list remains.

Silly, yes. Arbitrary, yes. But it wouldn’t be a game if it didn’t have rules.

Parkhurst’s Junco: The Career of a Quotation

It’s one of the infallible signs of the season. Sitting inside on a chilly day, a cup of hot chocolate warming the hands and busy feeders cheering the heart, every year about this time you can watch it creep across the internet: the description of the slate-colored junco as “leaden skies above and snow beneath.”

I’d love to know who’s behind the e-revival of that particular bit of kitsch. Or do you suppose that everybody is quoting the phrase directly from its source, Howard Elmore Parkhurst’s The Birds’ Calendar?

Parkhurst’s “informal diary” is now virtually unknown — apart, of course, from that throwaway line about the juncos. But it marks the birth of a very special sub-genre in the literature of American birding, namely, the Central Park memoir.

The observations here recorded, with slight exceptions, were all made in that small section known as “The Ramble,” covering only about one-sixteenth of a square mile…. Within this little retreat I have, during the year [1893], found represented nineteen of the twenty-one families of song birds in the United States; some of them quite abundantly in genera and species; with a sprinkling of species from several other classes of land and water birds.

Among the birds Parkhurst encountered in January was

the snow-bird, a trim and sprightly creature about six inches long, dark slate above and on the breast, which passes very abruptly into white beneath, as if it were reflecting the leaden skies above and the snow below…. Their sleek and natty appearance and genial temper commend them at once to the observer.

And Parkhurst’s “attractive” prose commended itself equally to the contemporary reader. His felicitous description of the junco appears to have been quoted abundantly in the first two decades of the twentieth century, almost (only almost!) always with an attribution to the author. It seems likely that Neltje Blanchan was the earliest vector of dissemination for the phrase, which passed from her Bird Neighbors into leaflets for schoolchildren, who no doubt were as taken by “Mr. Parkhurst’s suggestive description of this rather timid little neighbor” as were his adult readers.

In the years that followed, however, the quotation was loosed from its authorial origins, most often to be cited anonymously. In his 1968 entry for the Bent Life Histories, Eaton followed that “modern” practice in noting only that the junco had been “aptly described as ‘leaden skies above, snow below'” — not bothering to tell us by whom. Parkhurst’s words still appeared in quotation marks, but they had plainly become part of a shared store of birderly lore, no more requiring attribution than the observation that the white outer rectrices are “prominent in flight.”

This has always been the path of a catchy phrase: invented by a single mind, admired by others, then finally taken over into a broader culture eager to forget that it ever had an origin. But the internet has introduced another, more sinister step.

Parkhurst’s words still circulate — especially this time of year — without his name attached. In a classic internet move, though, a google search now, once again, turns up the quotation with an attribution.

Thoreau described [juncos] as “leaden skies above, snow below.”

I don’t know all of Thoreau. I don’t remember those words in what I have read of the oeuvre, though, and it seems suspect to me that the earliest printed assertion of his authorship (thanks, google) should be from no more than four years before the Mother Jones quotation above. Surely in the 101 years between Parkhurst’s Calendar and 1994 someone would have pointed out the theft. I’m left wondering whether the credit to Thoreau isn’t — gasp — made up, as are so many (it sometimes seems like most) of the attributions on the internet.

It’s one of the unhappy elements of this e-world that it’s awfully easy for us to just say things, whether they’re true or not. But, in an encouraging paradox, the same casual convenience lets us go ad fontes in search of the truth: it takes hardly more time to look up “leaden skies and snow” than it does to decide to type the name “Thoreau.”

So here, a couple of weeks early, is my 2015 resolution: To give Howard E. Parkhurst credit for everything he said or wrote, and to resist the easy temptation to throw attributions around at random.

Who’s with me?

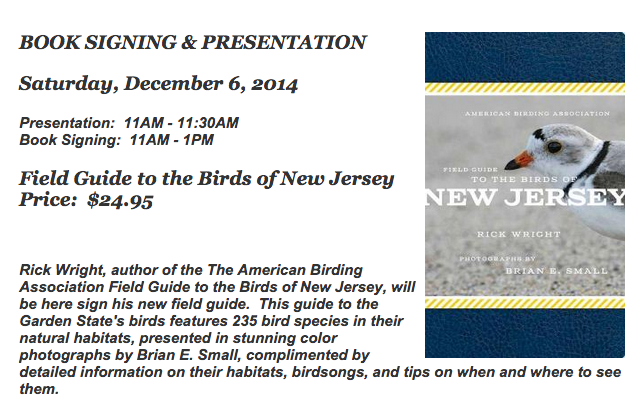

Tomorrow at Wild Birds Unlimited, Paramus

Wild Wigeon Wonderings

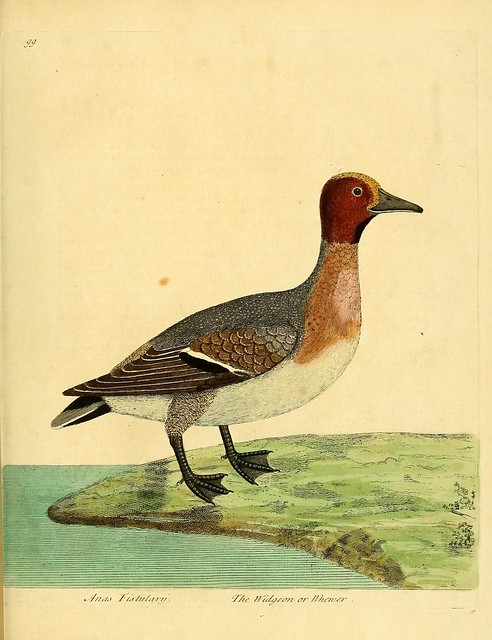

Eleazar Albin gives three different names for the bird we know as the Eurasian wigeon: the more or less expected “Widgeon,” the lovely and onomatopoetic “Whewer,” and the puzzling Latin “Anas Fistularii.”

“Fistularis,” of course, is an ancient name for this species, going back beyond Gesner, and the source — or perhaps the reflex — of such vernacular names as “Pfeifente” and “siffleur,” all of which, like Albin’s “Whewer,” refer to the drake’s voice. Charleton says the bird

is so named for the rather sharp sound that it makes, like that of a shepherd’s pipe (fistula),

an explanation that makes perfect sense.

But Albin changes it, on his plate and in the caption to his short text. Instead of “the piping duck,” his wigeon is “the piper’s duck,” and I wonder whether there is not a meaning behind his emendation.

Ducks have been taken over live decoys, “call ducks,” since the first human noticed how tasty they were under all those feathers and down. To increase the attractiveness of their spread, fowlers — as they still do today — imitated the vocalizations of their quarry.

Might Albin be using “fistularius” here to refer to the whistling wildfowler, and might the anas be “his” in the sense that it was a frequent or a favored decoy species? We know from Albin himself that the bird was not of high culinary repute, so perhaps local hunters were more likely to use it as a decoy than a meal.

Plausible enough, isn’t it? Now all we need is an attestation of “fistularius” in that context, and some evidence that wigeons were used preferentially as lures.

Yeah, that’s all. Simple.