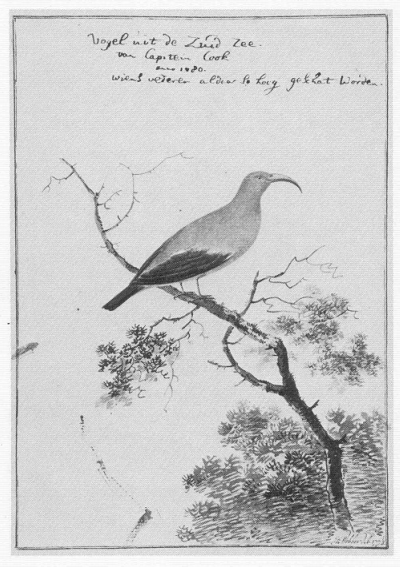

The stunningly scarlet and black iiwi was the first endemic Hawaiian landbird known to European science: it was the first to be drawn by a European — in 1778, by John Webber aboard Captain Cook’s Resolution — and the first to be formally described — two years later, by Georg Forster.

Forster, who had accompanied his father on Cook’s second voyage, was professor of natural history at Kassel when the German sailor Barthold Lohmann brought him the type specimen — now lost — of what Forster named the “carmine treecreeper.” A testimony to the considerable excitement with which discoveries from the South Seas were welcomed, Forster’s description appeared in print a scant three months after Cook’s ships arrived, without the late Cook himself, in London.

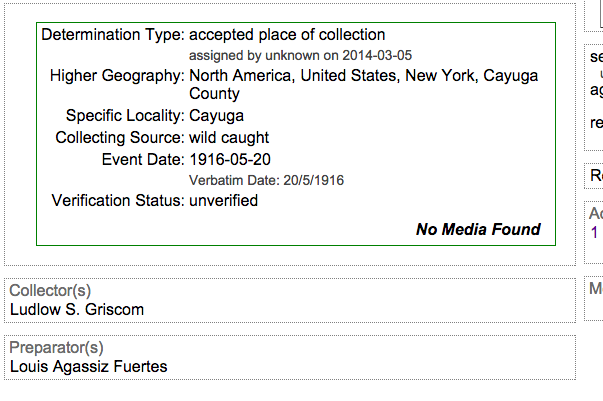

Most of the bird skins from the voyage remained in Britain, but as early as December 1780, Forster had seen no fewer than three specimens of his Certhia coccinea, well justifying his claim that the bird was “decidedly common” in its native range. Indeed, the expedition’s surgeon, William Anderson, recorded “great numbers of skins” of this species offered up for sale by the Hawaiian natives,

often tied up in bunches of 20 or more, or [with] a small wooden skewer run through their nostrils.

Forster’s type was apparently one of those that had been tied rather than skewered, as he describes in detail the characteristic operculum covering the nostrils.

The Hawaiians, it turns out, had not collected all those iiwis just to please their European guests.

In Forster’s words, the natives of Hawaii

make ornaments and various articles of clothing using the feathers of this bird, which must be extraordinarily abundant there given that such items are not at all rare. Mostly, capes are thoroughly covered with feathers, but the young women also wear necklaces, as thick as a thumb, made entirely of such feathers. For ceremonial dances, they weave as many of seven of these bands around their heads…. Barthold Lohmann … has donated one of these necklaces to the royal museum here [in Kassel].

But what exactly were, in the systematic sense, these birds that gave their brightly colored feathers and their lives to the lush beauty of Hawaiian featherwork? Forster in his original description

had no hesitation in assigning this new species [Gattung] of bird to a place among the treecreepers….

He considered and rejected the possibility of affiliating his new bird to a more exotic group:

Only its bill shape suggests any connection to the birds of paradise, in that it is bent like a scimitar, but shows not a sharp culmen, as in the other treecreepers, but a convex culmen. Incidentally, in the collections of the Landgrave of Hessen’s natural history museum, I have had the opportunity to discover that there are both curve-billed and straight-billed species [Gattungen] in the family [Geschlecht] of birds of paradise…. Already on my trip around the world I noted similar variation among other species [Gattungen], without feeling myself justified in increasing the number of families [Geschlechter]. A treecreeper from Tongatapu has fleshy wattles or beards… and two further species from New Zealand… are distinctive for their stronger, longer feet, just like the one [namely, the iiwi] lying before me.

John Latham was of the same opinion, retaining the species in the genus Certhia in his 1790 account; inexplicably, Latham took it upon himself to replace Forster’s perfectly good epithet coccinea with vestiaria (“of clothing”), an invalid alteration that would nevertheless give rise to a widely used genus name for the iiwi. Even as late as 1820, Louis-Pierre Vieillot agreed that the “eee-eve” (another example of the great French ornithologist’s struggles with written English) was simply the representative of “a different tribe” of treecreepers found in the South Pacific.

There were competing taxonomic assessments, though. Blasius Merrem reported finding a specimen in the museum at Göttingen (kept there with a fine example of featherwork) labeled with the name “Red Humming-Bird.” Merrem moved the erstwhile treecreeper into the genus Mellisuga, erected in 1760 by Mathurin Brisson for the vervain hummingbird; in 1783, Joseph Märter shifted it into another Brissonian hummingbird genus, Polytmus.

The most influential early recognition that the iiwi was not a close Certhia relative (and indeed not a hummingbird, either) came in 1820, when Coenraad Jacob Temminck described the genus Drepanis on the basis of the now extinct Hawaii mamo; his new genus also included the iiwi.

Today, following a suggestion first offered by R.C.L. Perkins in 1893, the iiwi and its finch-like Hawaiian relatives are recognized as a close assemblage within the “winter finch” subfamily Carduelinae. Support for grouping them together is provided by a range of shared features, including similarities in plumage, musculature, tongue structure, nostril structure, and vocalizations.

And smell. Odor. Scent. Aroma. Fragrance. Stench.

Perkins was the first western scientist

to notice the scent emitted by so many and so different species of Hawaiian birds. I cannot liken this scent to any other that I know; but I should certainly call it disagreeable.

It was in fact “the peculiar odour” like that of mildewed canvas that first led Perkins to conclude that the thin-billed and the thick-billed Hawaiian honeycreepers belonged to one and the same family. The smell, apparently produced by the uropygial gland, is said to be so strong that it contaminates the feathers of birds placed in the same museum drawer with honeycreepers, and traces of the odor can be transferred from specimen to specimen by the hands of researchers.

Which raises a question, I think. Heinrich Zimmermann, Cook’s coxswain on the third voyage, noted that one only rarely saw the red feathered cloaks and capes worn, which led him to believe that their use must be largely restricted to religious ritual. I wonder, though, if perhaps, for all their visual splendor, they weren’t just too smelly.

The iiwi is the 2018 Bird of the Year of the American Birding Association.