The first scientific description of the Wilson’s phalarope was written by French ornithologist Louis Jean Pierre Vieillot in 1819. The bird is named after ornithologist Alexander Wilson.

Well, kind of.

The alert reader of the News-Leader‘s news ( a bit of poésie trouvée there, hm?) will have noticed that in fact only the English name of this common sandpiper commemorates the Father of American Ornithology. Its scientific epithet, on the other hand, is tricolor, in clear reference to the lovely red, white, and blue plumage of breeding adults, especially female adults.

How did that happen?

This species has a relatively short history in western ornithology. It was first described not by Vieillot but by the Spanish explorer Félix Azara, who purchased a specimen in Paraguay. Collected in December, Azara’s skin was not in its bright breeding plumage, and so the name he gave it — “le chorlito à tarse comprimé” — signals instead the remarkable shape of the foot, four times, he says, as wide in one dimension as in the other.

“Chorlito with flattened shanks,” of course, is not an acceptable name by the standards of Linnaean taxonomy. It was Vieillot, ten years after the publication of Azara’s Voyages, who first assigned the species a proper binomial.

The genus Steganopus is established on the sole basis of the description that M. de Azara gives of a bird seen in Paraguay, which he considers a quite separate species and only distantly related to his chorlitos (shanks and tringas), distinctive not only in the shape of its bill but also in its tarsi, which are so extremely flattened on the sides….

This species Vieillot names Steganopus tricolor, and tricolor remains its epithet today, whether is assigned, as it has variously been, to the genus Phalaropus or to Vieillot’s Steganopus (“an excellent genus,” writes Coues).

The only problem is that — as so often — Vieillot’s work was little known to English-speaking ornithology. The year after he published his description in the Nouveau dicionnaire, Joseph Sabine (brother of Edward Sabine) announced an

exquisitely beautiful bird, it is believed … never before been described or come under observation. It was received in the collection despatched from Cumberland House, in the spring of the year 1820.

Writing in the Zoological Appendix to Franklin and Richardson‘s Narrative of a Journey to the Shores of the Polar Sea, Sabine named the “new” bird Phalaropus Wilsoni, expressing his hope that

the specific appellation will … be considered a proper compliment to the individual who has so often been quoted in [the Appendix]; in affixing his name to an American bird, it is proposed to record the renown amongst naturalists, which that quarter of the world has acquired by his labours in Ornithology.

Sabine was a great and outspoken fan of his late colleague:

Untaught, and without the aid of scientific books, he has produced a work which, for correctness of description, accuracy of observation, and acuteness of distinction, will compete with every publication of natural history yet extant: nor is it alone on these excellencies that the character of his book stands so high; the beauty of the style, and perspicuity of the narrative, add unrivalled charms to its scientific merits.

Though Sabine’s scientific name is invalid, of course, there is no such thing as “priority” in English names, and it has been Wilson’s Phalarope in the vernacular ever since.

But there is a great irony at work here.

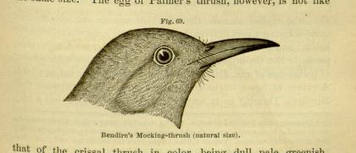

After Wilson’s untimely death 200 years ago yesterday, his friend, patron, and literary executor George Ord saw Volume 8 of the American Ornithology through the press, then undertook to assemble and publish Volume 9, relying on the drawings, paintings, notes, and texts Wilson had left behind. That volume appeared in 1814, and among the birds it treated was one identified by Ord as the Gray Phalarope, Phalaropus lobata. Ord writes:

Of this species only one specimen was ever seen by Mr. Wilson, and that was preserved in Trowbridge’s Museum, at Albany, in the state of Newyork. In referring to Mr. Wilson’s journal I found an account of the bird, there called a Tringa, written with a lead pencil, but so scrawled and obscured that parts of the writing were not legible…. From the drawing, which is imperfectly colored, and the description which I have been enabled to decipher, I have concluded that this species is the Gray Phalarope of Turton.

The only problem is that the bird in Wilson’s drawing, and in the plate, above, engraved from it, is not a Gray Phalarope (we call it the Red Phalarope in the Americas) at all — but a fine female Wilson’s Phalarope in bright breeding feather. Wilson’s description, as given by Ord, is also clearly that of the unrecognized tricolor:

The bill of this species is black, slender, straight, and one inch and three quarters in length; lores, front, crown, hind head and thence to the back very pale ash, nearly white; from the anterior angle of the eye a curving stripe of black descends along the neck for an inch or more; thence to the shoulders dark reddish brown, which also tinges the white on the side of the neck next to it; under parts white….

We can’t blame Ord — “I have not had an opportunity of seeing the bird,” he reminds the reader — but Alexander Wilson had in fact discovered, described, and painted the very bird that would be named for him by Sabine seven years after his death in 1813. Charles Lucian Bonaparte put it neatly 25 years later: Wilson,

had he lived to publish the species himself, would doubtless have fixed it on the same firm basis as in other instances of the kind.

But if Wilson had described the bird, he would certainly not have named it for himself. Things sometimes work out in spite of themselves.