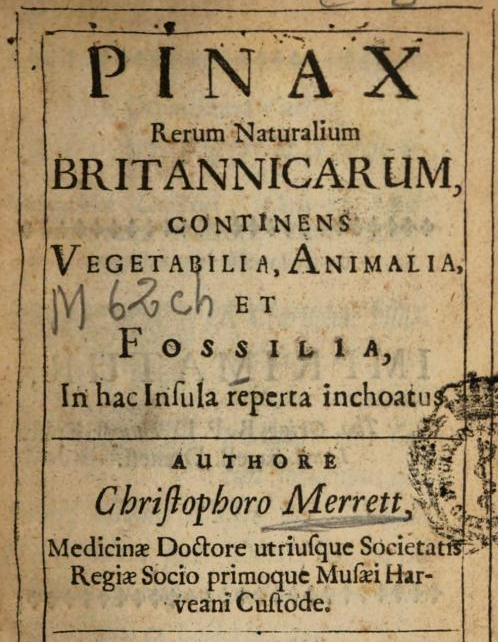

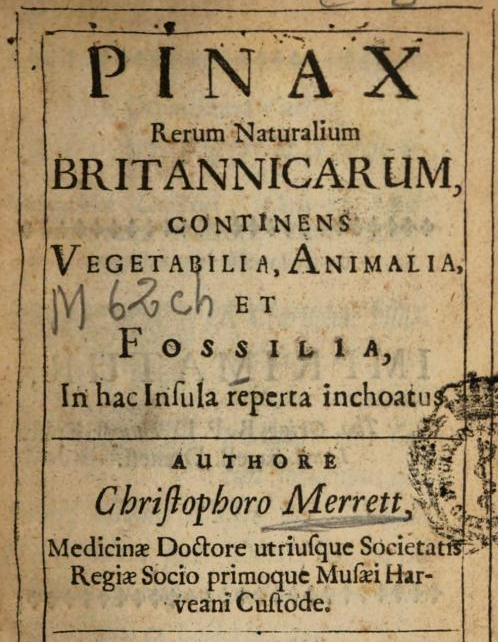

As near as the history of calendar reform lets us tell, today is the 400th anniversary of the birth of Christopher Merrett, author of the first complete list of the birds of Britain.

His Pinax rerum naturalium britannicarum, first published in the annus mirabilis/horribilis of 1666, covered all the plants, animals, and fossils known from the island.

As a physician, Merrett was naturally most well-versed in botany, agreeing with his predecessors that

plants were of greatest use in helping the human race, in so far as they sustain human life and protect and restore human health.

As to the birds, he tells the reader in his Introduction that he consulted in large part

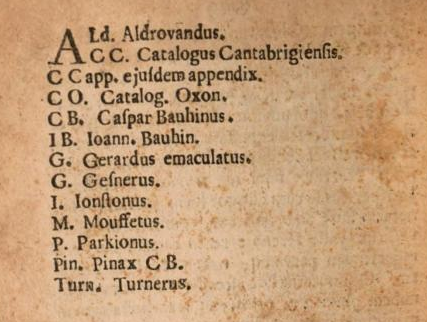

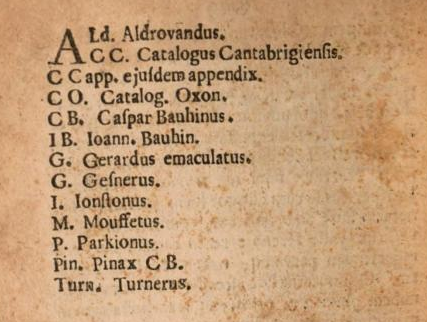

Gesner, Aldrovandi, and Johnston, who have all treated them quite fully; and in some cases, our Turner, that most industrious researcher of his day, who published a book on birds that, though light in weight, was substantial in good judgment.

Merrett cites other sources passim in the list itself, among them

that noble man Dr. Willoughby, the most diligent and most intelligent investigator of nature not just throughout Britain but over the greater part of Europe.

Most of the catalogue of birds relies on records published by those authorities, but Merrett also includes a few of his own sightings, including that of “a Skreck,” also known, he says, as “the Butcher, or murdering Bird”:

I have seen it three or four times in the summer near Kingsland.

Of the Nightjar, he notes that a Sir Cole collected one on Hampton Heath in 1664, “quite a rare bird.”

Merrett also offers his clarifications of the reports of others:

Cornix aquatica. Turner saw this bird on the river banks…. I tend to believe that it is the murre of Cornwall.

Some of those corrections, including this one, are nothing but Verschlimmbesserungen. As Mullens points out,

this is the Water-Ouzel, or Dipper. Merrett has been misled by Turner’s use of the Northumbrian name “Watercraw” … and has placed it among the Corvidae. He has further confused the matter by suspecting it to be the Cornish “Mur” … the Razor-Bill.

Merrett also passes on some facts that strike the modern eye as unlikely.

Barn Swallows, he says, spend the winter in marshes and seashore cliffs in Cornwall, and it is a shame that in between the Eurasian Oystercatcher and the Crossbill Merrett — not unlike so many of his contemporaries — should have listed the “Bat, Flittermouse, Rearmouse,” a bird that appears on summer evenings and spends the winter hidden away in cellars.

One source Merrett relied on that is no longer available to most of us was the ornithopolae of London — the bird sellers. It was from them that he had his knowledge of several species, especially of certain less common waterfowl.

The “Gaddel” — our Gadwall —

is known by that name to our birdcatchers; it is a bird of the size of a Mallard, its bill very like that of a teal, but somewhat more bluish.

A Mr. Hutchinson, bird merchant in London, informed Merrett about three species that he claimed to have seen on the plains around Lincoln.

The Nun [the Smew] is a water bird, slightly smaller than a teal; it has a round, thin, narrow bill, a bit curved on the upper mandible, and it is whitish on all its underparts, blackish above. The head is crested, whence it may well have its name, that is a say, from a nun wearing a hood.

Hutchinson and Merrett’s “Crickaleel” appears to be the Garganey, described as a small duck with blue on the upper wing. Their “Gossander” is more mysterious. This is a bird

with webbed feet and a crest. Its belly is yellow, its bill long and narrow. The flesh, fully cooked, turns yellow and then is transformed into oil; it is not edible. From the fields of Lincoln. This seems to be a type of “puphinus.”

It’s not clear at all whether this bird is a duck, an auk, or a shearwater, though its origin in Lincoln suggests that it may in fact have been simply a Goosander in the modern sense, a Common Merganser, with an overlay of characters from another species or two.

Obviously, Merrett’s list is of little value today to anyone hoping for an up-to-the-minute assessment of the avifauna of Great Britain. But it remains, 400 years after its author’s birth, an invaluable document of the process of ornithology at the turn of an era, when the corpses hanging in birdcatchers’s stalls, the traditional hearsay of medieval natural historians, and observations recorded by the first empiricists could all find their place in an authoritative avifauna.