The end draws nigh.

The end of the warblers as most of us know them.

It’s likely to still take a year or six, but it seems as if that long-familiar assemblage known as the American wood warblers is finally going to be … disassembled. And when that happens, the yellow-breasted chat will be leading the flight from a monolithic Parulidae into new, and in some cases perhaps uncertain, taxonomic seats.

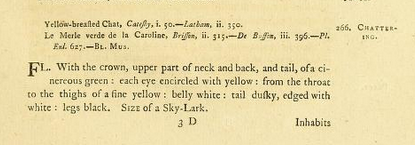

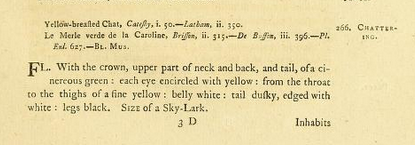

Beginning with the first edition of the Check-list, published in 1886, the AOU simply embedded this big, noisy, thick-billed creature among the other wood warblers without comment. It took almost a hundred years and five more versions of the list for the Committee to issue the express warning that, in the words of the sixth edition, the

allocation of the genus is in doubt; it may not be paruline.

The world turned upside down! Happily for those clutching their field guides in existential dread, the seventh edition made everything right again, assuring us that

although placement of this genus in the Parulidae has been questioned frequently [with citations to here and here]… molecular data support its traditional placement

among the wood warblers.

What a relief. “Molecular data” are, after all, so authoritative. So definitive. So soothing.

What has always caught my eye, though, once I’ve finished wiping the tears of joy from it, is that other phrase in the Check-list‘s reassurance: “traditional placement.” My family has traditions; yours does. too. And so, most likely, do warbler families (worms at Thanksgiving, worms at Christmas, worms at Easter, worms on birthdays and anniversaries!).

Taxonomic traditions are of a different nature, though, and we’re well within our rights to ask whether there really is such a tradition, who started it, and why. And were other, competing traditions suppressed with the stroke of a pen a century and a quarter ago, when that first Committee located the chat between the yellowthroats and the old Wilsonia warblers?

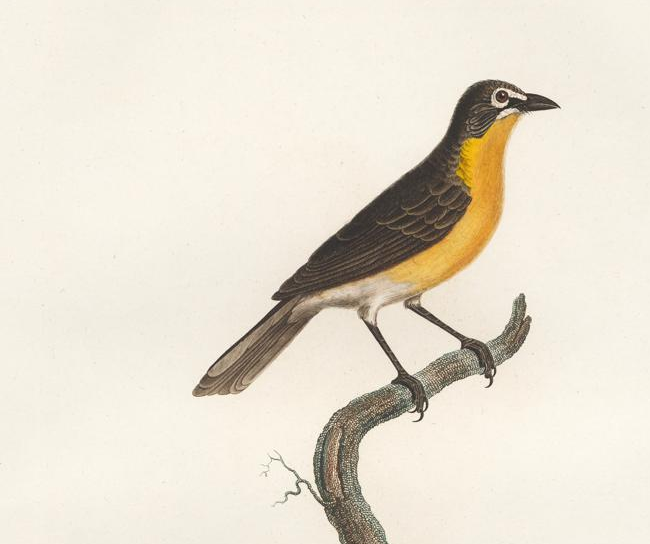

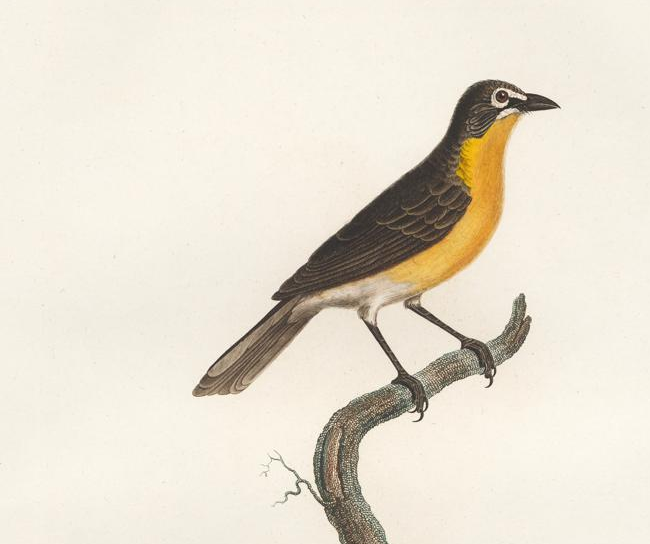

As is the case for so many of our common eastern birds, it was Mark Catesby who gave us the first detailed account of the bird we know as the yellow-breasted chat.

Exploring the American southeast 300 years ago, Catesby found this species wild and retiring, entirely absent from “the inhabited Parts” of the country; instead, he writes, they

frequent the Banks of great Rivers; and their loud chattering Noise reverberates from the hollow Rocks and deep Cane-Swamps.

The traveling naturalist anticipated the laments of many birders even today when he complained that these “very shy Birds … hide themselves so obscurely.” In fact, after many hours’ effort on his own, Catesby had to hire an especially skilled native to secure the specimen he would so delightfully paint in its song flight.

Catesby was equally prescient in his uncertainty as to just what this bird is.

“Chat,” of course, is about as polysemic as a bird name gets, and Catesby’s Latin name, “oenanthe americana pectore luteo,” isn’t much clearer. Now restricted to a single well-defined genus of, well, chats, the name “oenanthe” — dating to Aristotle and beyond — was applied in those pre-binomial days to wheatears, whinchats, stonechats, linnets, whitethroats, and others. Catesby’s French translator, that anonymous

very ingenious Gentleman, a Doctor of Physick, and a French-man born,

decided — most likely without consulting the author — that this “chat” was an example of the first of those “oenanthes,” a “cul-blanc,” a wheatear.

Linnaeus wasn’t buying it. In 1758, he assigned this bird — which he never saw in life or in skin — the final place in his genus Turdus, which he characterized as possessing

a sharp bill, round in cross section, with the upper mandible decurved at the tip. The nostrils are bare, half covered by a thin membrane. The tongue is bifurcated.

He distinguished the species Turdus virens — which he based expressly on Catesby’s painting — from the other “thrushes” by its dusky green color, yellow underparts, and white supercilia.

In a rare show of international peace and understanding, Johann Michael Seligmann, Jacob Theodor Klein, and both of the authoritative French ornithologists of the time, Brisson and Buffon, followed Linnaeus in considering our bird a thrush.

That unanimity — that “traditional placement” — did not last, however.

Somehow, somewhere, the Swedish collector and diplomat Gustavus Carlson appears to have acquired a skin of Catesby’s chat — to my knowledge, the first in any European cabinet. Oddly enough, though, when it came to cataloguing Carlson’s collection, Anders Erikson Sparrman, who had studied under Linnaeus in Uppsala, failed to recognize the bird as his Master’s Turdus virens; in his Museum carlsonianum, Sparrman names the perilously posed specimen instead Ampelis luteus, placing it in a genus that then comprised the waxwings and half a dozen cotingas.

English ornithologists in the late eighteenth century took a different approach. John Latham moved Catesby’s wheatear-chat, which at the hands of the continentals had become a thrush, to a place among the tyrant flycatchers.

Two years later, Thomas Pennant in his Arctic Zoology situated the bird he knew as the “chattering tyrant” between the fork-tailed flycatcher and the great crested flycatcher.

Neither Latham nor Pennant gave this noisy flycatcher a scientific name. Thus, in 1788, when Johann Friedrich Gmelin published his new edition of the Systema, he was forced to rely instead on the hints provided in the English names “flycatcher” and “tyrant,” names that persuaded him to move the chat-like bug-catching thrush into the very large genus Muscicapa, which at the time united all sorts of vaguely flycatchery birds in a decidedly miscellaneous lot– among them a number of only distantly related species, from the Old World and the New, known today as “warblers.”

Twenty years later, Louis Jean Pierre Vieillot — still, all efforts to the contrary notwithstanding, the least-appreciated of early American ornithologists — stepped in to clear matters up. And he did so in no uncertain terms. After acknowledging the accounts of the chat provided by Brisson, Buffon, Linnaeus, Latham, and Gmelin (he seems to have overlooked Sparrman), Vieillot observes that

all those authors seem to me to have done nothing but describe the bird in reliance on Catesby…. No other ornithologist claims to have seen the bird in nature, such that it must seem that the taxonomic assignments have been made solely on the basis of the figure published by Catesby.

And, he continues, “that figure being inaccurate” like so many of Catesby’s paintings, it inevitably proved to be the occasion for such a wide and conflicting variety of taxonomic views.

Vieillot sweeps all of that confusion away by assigning the bird to an entirely new genus, Icteria, and coins the novel vernacular name “ictérie dumicole,” the thicket-dwelling icteria.

Vieillot was moved to iconoclasm above all by the bill of the bird,

thick, sharp-pointed, and without any notch,

more closely resembling, he says, the bill of the troupials than of any other bird. He admits that the chat’s bill differs from those of the typical blackbirds and orioles in its arched culmen and the presence of bristles at the base, but it is even more thoroughly unlike those of the thrushes and flycatchers.

I have thus found myself obliged to correct the false naming, and as I find no other genus that combines the characteristics possessed by this bird, I make of it the type species of a new genus,

namely, Icteria, an appellation usually said to refer to the yellow underparts of the bird but, as a reading of Vieillot makes clear, more likely meant by its author to indicate that similarity to birds of the genus Icterus.

Refreshingly, Vieillot has a lot to say not just about the structure and appearance of his new icteria but its behavior, as well. He obviously watched these birds closely –and collected a good series of both sexes — during his stay in the United States as a refugee in the 1790s, and his notes are of sufficient value and interest to merit a long excerpt:

This icteria eats insects and berries…. Shy and distrustful by nature, it keeps to the thickest parts of the brush, and when it does come out to feed, it again seeks refuge in the thicket once it is disturbed…. This species arrives in Pennsylvania and New York in May, and leaves those regions in autumn. Catesby says that in southern Carolina it is encountered only at a distance of three hundred miles from the sea; in contrast, in the northern states it commonly frequents areas no more than a mile from the coast. It seeks its food in open areas, often on the ground, but always close to its favored retreat, whence the male emerges by mounting perpendicularly to a height of thirty or forty feet, where it turns a pirouette while descending with its feet hanging down, soon plunging into the fastness of the brambles. I have observed that he he flies this way only when singing and only during the breeding season.

Vieillot never succeeded in finding the nest of this species, but he assumes that the clutch is of four eggs,

since that is the number of young that I have often seen accompanying their parents when they were still in need of the adult birds’ care.

Vieillot places the account of his dumicolous icteria between those of the vireos and those of the todies. It is not obvious here whether mere position indicates relationship; even though he has told us, loud and clear, that this is not a flycatcher or a thrush or even an icterid, we’re still left wondering just where to file the renamed species.

Not until 1834 would Vieillot explicitly place his ictérie in the third “division” of his family of “weavers,” immediately following the orioles and the Old World weaver finches of the genus Ploceus.

Alexander Wilson published his natural history of the chat in the same year as Vieillot’s. Though neither author’s text provides any acknowledgment of the other’s, they share, nearly verbatim, the description of the male‘s

mount[ing] up into the air, almost perpendicularly, to the height of thirty or forty feet….

I do not know which direction influence flowed here, but it seems very unlikely that these passages were composed independently. It may be worth pointing out that the so memorable first line in Wilson’s account,

This is a very singular bird,

echoes closely the beginning of his mentor William Bartram’s brief summary of the same species, which he called Garrulus australis, literally the “southern jay”:

The yellow-breasted chat … is in many instances a very singular bird.

My suspicion is that both Wilson and Vieillot had profited from an unpublished description supplied to both by the Philadelphia naturalist, making Bartram the first scientist to fully describe the song flight of the yellow-breasted chat.

Like Vieillot (and like Bartram), Wilson tut-tuts over the Europeans’ failure to identify the bird’s true taxonomic affinities. Unlike Vieillot, however, Wilson was content — “almost” — to assign the chat to an existing genus and family:

In short, tho this bird will not exactly correspond with any known genus, yet the form of its bill, its food, and many of its habits, would almost justify us in classing it with the genus Pipra (Manakins), to which family it seems most nearly related.

In honor of the chat’s “strange dialect,” Wilson headed his account with the novel binomial Pipra polyglotta. Charles Bonaparte, in a characteristically delicate formulation, found this “not a little remarkable.”

The bird he placed in [Pipra] has certainly no relation to the Mannakins, nor has any one of that genus been found within the United States.

Bonaparte was no happier with the treatment Vieillot gave the species in his Analyse, where he listed the “ictérie” as a member of the family Texores, “weavers.” Just a year later, obviously influenced by Vieillot’s classification and led astray, perhaps, in part by an old misidentification in Desmarest’s Tangaras, Georges Cuvier put forth another idea: the yellow-breasted chat is a transitional species between the tanagers and the African weavers. Lichtenstein, too, had identified Deppe’s Mexican specimens of the chat as representing a new tanager and named them Tangara auricollis.

The allocation of this species to the tanagers proved a dead end. In 1832, Thomas Nuttall placed his yellow-breasted icteria between the warblers and the vireos. Audubon, in the Synopsis of 1839 and in the octavo edition of the Birds of America, stubbornly followed Wilson in assigning “this singular bird” (that phrase again!) to the family of the manakins. The real trendsetter, though, was Charles Bonaparte, who listed the species as a member of his family Vireoninae in 1838.

There things stood, with the chat deemed a sort of aberrant vireo, for twenty years. Then, Spencer Fullerton Baird, acknowledging “much contrariety of opinion among ornithologists” about the correct classification of Icteria, nevertheless found

no reason why it may not be assigned to the Sylvicolinae [the warblers], possessing, as it does, so many of their characteristics. The bill is stouter and more curved than the rest, but the other characters agree very well. It cannot properly be placed with the vireos and shrikes….

Baird assigned the chat — which he, too, called “this very singular bird” — to its own almost unpronounceably vowel-rich “section” among the warblers, Icterieae. Fifteen years later, he, Ridgway, and Brewer, in the History, elevated that section to a subfamily, Icterianae.

Uncertainty persisted, of course. Salvin and Godman wrote in 1879 that

even now [Icteria] cannot be said to have found a final resting place, as much of its internal structure has yet to be examined and compared with that of the birds with which it has been associated. For a long time it was placed with the Vireonidae, of which it was obviously a very abnormal member. Its relationship with the Tanagridae has also been suggested. in placing it here, in the midst of the Mniotiltidae [= Parulidae], we follow in a great measure Prof. Baird’s assignment….

Elliott Coues, though in the first edition of the Key he retained the Bairdian subfamily Icteriinae for the chat and its apparent “allies” in the tropics, observed that

it is perhaps questionable whether they are most naturally classed with the Warblers.

Even thirty years later, the final edition of the Key reminds us that

the position of Icteria … is open to question…. It is probable that the final critical study will result in a remapping of the whole group.

Nevertheless, Baird’s identification of the chat as a warbler became the accepted one, the conventional one, the “traditional” one — after a century and a half in which the bird drifted from the wheatears to the thrushes to the tanagers to the manakins to the weavers to the vireos and back.

No “critical study,” molecular or otherwise, will ever be “final,” but the latest review of the advanced passerines concludes that Baird’s warblerization of the yellow-breasted chat was, in fact, less perceptive — or less lucky — than Vieillot’s characterization of his new genus:

The dumicolous icteria more closely approaches the troupial than any other bird, thanks to its strong bill with a fine, sharp tip and no notches.

Indeed, Barker et al. discover that their “concatenation results” — I do not know what that means — support an arrangement in which the yellow-breasted chat is “the sister lineage to the blackbird family Icteridae.” To reflect that relationship, their proposed taxonomy removes the chat entirely from the warblers, placing it in its own family, Icteriidae.

A family whose name is ultimately based on the old “section” Icterieae, a section created and a name coined by Spencer Baird, who was responsible for the “traditional” placement of the species among the warblers, a placement we’re all going to need to work hard, one of these next years, to forget.