Among the birds discovered by Freyreiss and Maximilian in Brazil was a glossy gray-green tanager, a lively bird encountered in almost every dense tangle of palm fronds along the coast.

But back up. “Discovered” may be saying too much.

As Maximilian himself pointed out, the palm tanager was already known to European science, just misidentified:

This bird has hitherto been treated as the female of the Tanagra Episcopus, and it is depicted as such in Desmarest. This is an error, however, as Tanagra Episcopus, or Sayaca (the Sanyaçú of the Brazilians of the east coast), is very different from this supposed female, a bird of which we have often received both sexes, which resemble each other quite closely. This latter bird, formerly thought to be the female, is entirely different from the Sanyaçú even in its very soft, twittering voice. Because it is constantly found among the cocoa palms, I name this bird Tanagra palmarum.

I have to confess that before I read this passage this morning, I’d forgot that the blue-gray tanager was named “bishop.” And now I’m wondering why.

This pretty and familiar tropical thraupid barely escaped being called virens, a name — meaning “greenish” — that would have made less sense even than most tanager names. Instead, thanks to some timely intervention by the ICZN, it still, again, bears the Linnaean epithet episcopus, making it one of those almost innumerable birds named for churchmen and churchwomen, from popes all the way down to nunlets and monklets. So how did Linnaeus come to name this tanager in particular episcopus, the bishop bird?

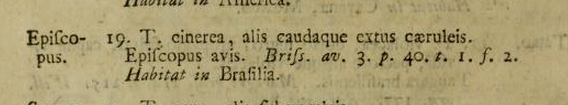

The short answer: It wasn’t his idea in the first place. We tend to credit (or more often to blame) the Swedish nomenclator for all the scientific names with his initial after them, but in fact, a goodly number — anybody know offhand just how many? — of the names in the Systema were not coined by Linnaeus but adopted from his many sources. This is one of them. Linnaeus called the tanager episcopus because Mathurin Brisson had done it first.

Brisson gives a very detailed description of the specimen in Réaumur’s cabinet, sent from Brazil by two French collectors; but he offers no clue as to why it should have been appointed bishop among the birds. Perhaps it was the episcopal hue of the lesser coverts, “grayish white with a hint of violet,” though that seems a bit of a stretch. More likely, I think, this was Brisson’s witty way of easing the transition between his accounts of the various tanager species and those that immediately follow in his Ornithologie.

What better way to introduce the full suite of cardinals than with a bishop?

Brisson’s gentle joke had, as they say, legs. Not only did Linnaeus immortalize the name episcopus, but his successors found in it the inspiration to create an entire little curia of ecclesiastical tanagers.

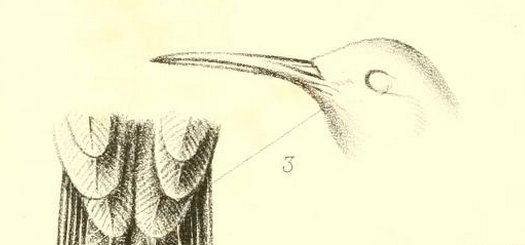

Desmarest, in his 1805 Histoire naturelle des tangaras, des manakins et des todiers, retained what he thought were both sexes of the “tangara évêque,” and added to the ranks a Peruvian bird brought to the Paris museum by a French collector, a bird he named Tangara archiepiscopus, the archbishop tanager.

Desmarest had access to specimens of both sexes of this species, resulting in the odd caption “the female archbishop” — surely something that led to a little bemused head-shaking even in Napoleonic France.

Unfortunately for Desmarest, this species, known today as the golden-chevroned tanager, had already been described by Anders Sparrman a generation earlier, from a specimen the Swedish naturalist thought had been collected somewhere in the East Indies.

Today, the bird is stuck, and we are stuck, with the accurate but not very evocative name Sparrman gave it: ornata.

Accuracy and priority proved only a minor setback to tradition, however.

In 1830, Hinrich Lichtenstein prepared a list of specimens sent back to Berlin by the German collectors Deppe and Schiede; those skins representing species already held in the Berlin museum were offered to private collectors “for cash payment in Prussian courants.” Some of those specimens represented still undescribed species, making Lichtenstein’s Preis-Verzeichniss the location of original publication. Among the nova: a yellow-green, blue-headed tanager with black wings with a yellow panel. Lichtenstein named it Tangara Abbas, the abbot.

It has been suggested, with no contemporary documentation, that “abbas” refers in a roundabout way to the given name of a man, Abbot Lawrence, who may or may not have met one or the other of the Deppe brothers sometime or another.

As far as I can discover, no one else has ever come close to believing that, and when this lovely little bird of Mexico and northern Central America hasn’t been called the yellow-winged tanager, it’s gone by the English name abbot tanager — not “Abbot’s,” as one would otherwise expect.

Apart from that slender shred, there’s an additional bit of far more convincing evidence that places this tanager, too, firmly in the tradition of ecclesiastical names.

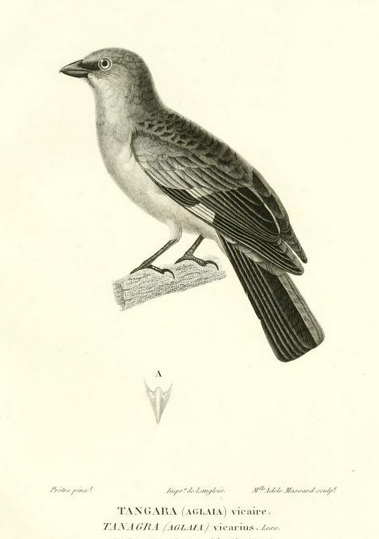

For all his great merits, René-Primevère Lesson was notorious — is still notorious — for the utter lack of respect he showed for other ornithologists’ nomenclatural acts. When Lesson turned to this species in 1831, which he found represented by several skins that had been shipped from Mexico to Paris (take that, Prussians), he simply renamed it, calling it Tanagra vicarius, “le tangara vicaire,” the vicar. Lest his reader overlook the clerical connection, Lesson compares the vicar to two other tanager species — the bishop (our blue-gray) and Tangara prelatus, the prelate tanager (Lesson’s name for the palm tanager).

Lesson was at it again in 1842. Eight years earlier, William Swainson had published a new bird he called the blue-shouldered tanager, Tangara cana; if I’ve kept up, this is now considered a subspecies of the blue-gray tanager (and I think it was this race that was introduced into Florida).

Lesson gave this taxon, too, a brand new name, Tangara diaconus, the deacon tanager. Could the theme be any clearer?

The synonymy of the tanagers is nearly as complicated as that of the hummingbirds, and has been so for more than 150 years. In the very middle of the nineteenth century, three ornithologists — Cabanis, Sclater, and Bonaparte — all set out, independently, to work out the relationships among the known species and to give them clear names, with the predictable result that not a few tanagers suddenly had three new names to go along with whatever old ones might have been attached to them before.

The eventual clearing up of the taxonomic mess, to the extent it was possible, was obviously a consummation devoutly to be wished; but it cost us those Lessonian tanager names, and with them a glimpse into what just may have been the longest-running gag in ornithological history.