The calendar and the weather agree: It’s still late summer in northern New Jersey. A month from now, things will be different, but for the moment, only the most foolishly impatient prodder of the seasons is thinking of winter birds.

Except, of course, on this date. It’s September 6. And every year on this day, we pause — don’t we? — to remember the only Oregon junco named for a New Jersey birder.

Eugene Carleton Thurber died in California on September 6, 1896, at the shockingly tender age of 31. Born in Poughkeepsie in 1865, Thurber moved to Morristown in 1881; a “promising young ornithologist, a careful collector, and a good observer,” he published his magnum (and perhaps solum) opus in November 1887, the List of Birds of Morris County, notable especially for its early records of the Lawrence’s and Brewster’s warblers.

Fragile health sent Thurber to California in 1889, where he

lived an out-of-door life in the field, collecting birds and mammals, as his health would permit, and preserving to the end his love for his favorite study.

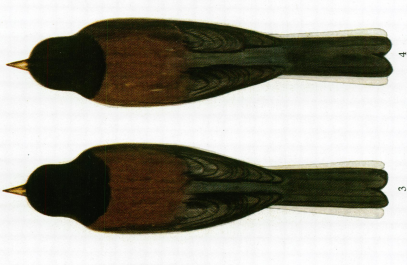

On May 24, 1890, Thurber collected two juncos on Mount Wilson in the San Gabriel Mountains. That summer, he showed the skins to Alfred Webster Anthony, another New York native exploring the Golden State; Anthony was “considerably surprised” to learn of juncos’

nesting in abundance within twenty-five miles of Los Angeles,

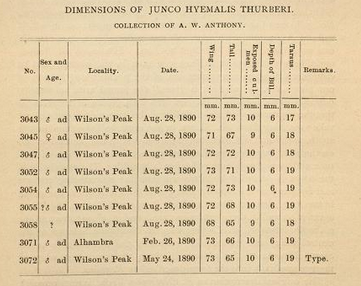

and as none of the other local collections seemed to include any similar specimens, he organized an expedition in late August to “obtain, if possible, a series of birds.” On August 27 and 28, Anthony found juncos “very abundant” between 5200 and 5800 feet elevation. He shot what seems to have been a total of eight adults, two juveniles, and one bird of unknown age and sex; all of those new adult specimens, however, were — as one might have predicted, without climbing the mountain in the first place — “in ragged moulting plumage,” inadequate for diagnosis.

So Anthony, apparently forgetting about Google Images, sent his little series, which by now included both of Thurber’s skins, to Washington, whence Robert Ridgway replied with some “rather unexpected” information: Anthony’s — Thurber’s — California juncos represented a “strongly marked” but still unnamed subspecies.

A deficiency, naturally enough, that Anthony promptly made up in the October 31, 1890, issue of Zoe:

I take pleasure in naming this handsome Junco for the discoverer, Mr. E.C. Thurber of Alhambra, Cal.

A few months later, having run through the juncos in a collection of birds purchased from Thurber in 1889, Frank Chapman was mildly skeptical: he pointed out that Anthony had failed to demonstrate that his new thurberi could be distinguished from the very widespread shufeldti.

The AOU, however, recognized the new race in 1892, and continued to list it as valid in the last Check-list to tally subspecies. BNA and Pyle, too, list thurberi among the Oregon junco subspecies. I’m glad we have a name for this population, whose recent colonization of the nearby California lowlands has provided some surprising insights into the rapidity of junco evolution.

Thurber’s early death kept him from leaving much of a biographical trail: We know a great deal more about the junco than the man. All the more reason to remember him once a year, I think, even if our juncos are still a month away.