Ducks are strong flyers, and large bodies of water shouldn’t pose much of an obstacle to them in any case, so it’s no real surprise that so many northern hemisphere species are found in both the Old World and the New.

Some of those shared ducks are more abundant on one continent than on the other, of course. Think of the lovely and bizarre little Harlequin Duck, a vanishingly rare bird in western Europe, but common enough in parts of North America.

In one of those coincidences of distribution that birders so much love to ponder, the harlequin’s range is nearly identical to that of another chubby duck of rocky seacoasts, the bird named in Gmelin’s 1789 edition of the Systema naturae Anas islandica — a bird that we now know in English, most of us, usually, most places, as the Barrow’s Goldeneye.

Gmelin’s text is really nothing more than a simple translation of that in John Latham’s Synopsis:

General colour black. Head crested: fore part of the neck, breast, and belly, white: legs saffron-colour. Inhabits Iceland. Called by the inhabitants Hrafn-ond.

“Raven duck” didn’t make much sense to Latham, so he gave the bird an English name that reflected its range as then understood: the Iceland Duck. Gmelin was happy to adopt the same name in Latin, Anas islandica, which in turn provided most of the national languages in Europe with a vernacular name for this rare visitor from the land of the Vikings.

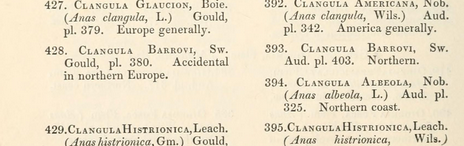

In the course of one of the Franklin Expeditions of the 1820s, John Richardson killed an unfamiliar duck “on the Rocky Mountains” of America. Unaware, it seems, of Gmelin’s Anas islandica, he described it as new and named it Clangula barrovii, the Rocky Mountain Garrot, the scientific name honoring Sir John Barrow and his “unwearied exertions for the promotion of science.” (In a footnote, William Swainson, Richardson’s prim-and-properer co-author, warns against naming birds after people, but admits that Barrow deserves such a tribute if ever anyone did, for his discoveries in “Arctic America, Southern Africa, and China; … high benefits conferred upon the State; and … the possession and encouragement of zoological knowledge.”)

That Richardson’s garrot was, in fact, the same goldeneye species that occurred as a vagrant in northern Europe was first recognized by Charles Lucian Bonaparte.

His Geographical and Comparative List of 1838 arrays the birds of Europe and America in parallel tallies; our little black and white duck occupies the same position in each column, but Bonaparte (unbound by the ICZN, obviously) opts for Richardson’s species name barrovi. The List does without English names, but the clear suggestion, of course, is that the bird would be known in the vernacular as “Barrow’s Duck” — precisely the name used by John Gould on the plate Bonaparte cites to from his Birds of Europe.

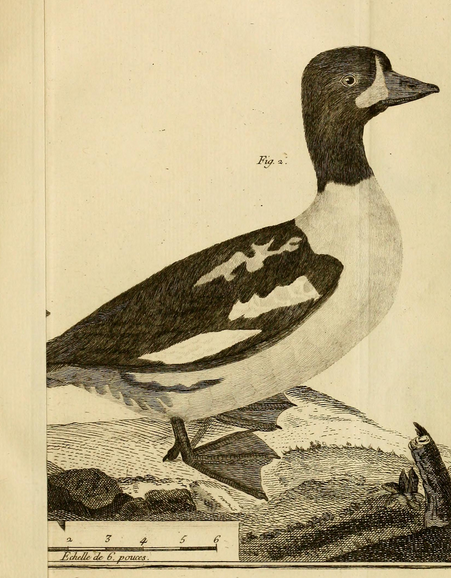

The extraordinary scarcity of this species in Europe is neatly attested by Eyton, in that same year of 1838: the author of the Monograph on the Anatidae knew of a grand total of three Old World specimens of Barrow’s Duck — one in his own collection, a recent specimen from Iceland, and a mount of unknown origin once in the collection of Réaumur and illustrated seventy years earlier in Brisson.

By 1842, Bonaparte at least had rediscovered Gmelin’s name, and was calling the duck islandica in his Catalogo metodico. In the English-speaking world, though, where the species was thought of as thoroughly Nearctic, and where the name of Barrow (he would live to 1848) was so celebrated, there was no reason to revive Latham’s old vernacular name — and plenty of cause to retain Richardson’s.

Thanks to Anders for asking —

Barrow’s and an apparent hybrid goldeneye